In Sandra de la Loza’s art, research—what she calls “the archive”—is central to her process. Treating archival material as mutable; she relies on it to expand narratives about history. She is also involved in community activism. Not everything she does is art, or at least happens in that context. But if art serves as a metaphorical megaphone, she uses it to broadcast loudly, aiming to erase the invisibility of marginalized communities.

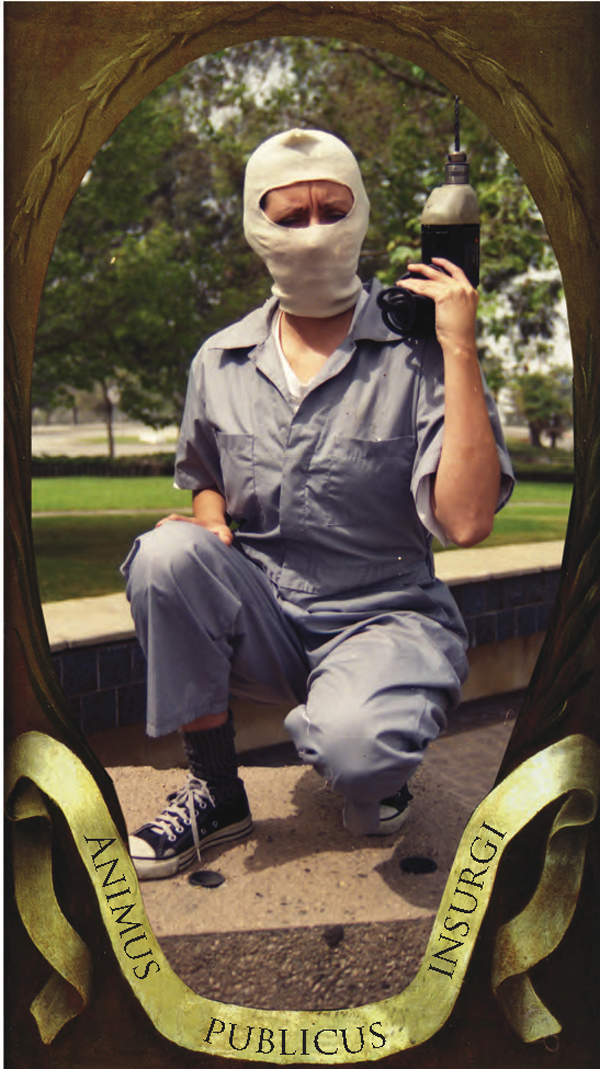

“Animus Publicus Insurgi” from The Pocho Research Society’s Field Guide to LA: Monuments of

Murals and Erased and Invisible Histories published 2010

Blending the roles of artist, activist and educator, de la Loza teaches social practice at Otis College. Social practice is also the subject of “Talking into Action, Art, Pedagogy, and Activism in the Americas,” a PST: LA/LA exhibition at Otis’ Ben Maltz Gallery. The show focuses on dialogues between Los Angeles and Latin American artists, and de la Loza collaborated with Buenos Aries artist Eduardo Molinari.

De la Loza was born and raised in LA—as were her parents—a factor that has significantly shaped her outlook. In a 2004 interview in Latin Art, she said: “My parents grew up at a time when Mexicans couldn’t live in certain neighborhoods, when they were physically hit in schools when they spoke Spanish. I was very conscious of how they internalized that and learned that their Mexican-ness was something they should erase, and how that was passed onto my siblings and me.” Her parents also experienced the Zoot Suit era, a time of emerging cultural pride. Looking at family photos, de la Loza noticed signs of an identity conflict in her parents’ poses. For an art project, she turned them into silhouettes.

Beyond family as subject, de la Loza began to focus on community and collective identity, now central to her practice. It comes from a desire to engage with others, and to create in spaces that aren’t as safe or predictable as the art world. These interests are evident in two of her best-known projects, both from 2011: a book, The Pocho Research Society Field Guide to L.A.: Monuments and Murals of Erased and Invisible Histories, and experimental videos presented in “Mural Remix,” a solo exhibition at LACMA and part of the first Pacific Standard Time.

Action Portraits, part of de la Loza’s solo show “Mural Remix” 3-channel video installation, with Joe Santarromana, 2011

For Operation Invisible Monument (2002), a collaborative piece presented in The Pocho Research Society Field Guide to L.A., she installed unauthorized historical plaques around downtown Los Angeles to commemorate the absence of Mexican-Americans in official accounts of city history. In a satirical portrait, she wears a ski mask, jumpsuit and sneakers, poised for action, drill in hand. Mural Remix included a documentary video that chronicles the history of LA’s street murals. In a 3-channel video installation, Action Portraits, their colors and patterns are projected onto the nude bodies of performers who brush paint on themselves to create a green-screen effect. Visually, the paint is replaced by the murals’ emblematic imprint on skin.

Postcard of Devil’s Gate, from Cartas Caminantes (Walking Letters), from “Where the Rivers Join” with Eduardo Molinari, 2017

Given the civic-minded nature of de la Loza’s work, her interests have compelled her to expand beyond art world contexts. In the Chicano-Latino communities of East Los Angeles, she advocates for poor working-class people adversely affected by the area’s rapid gentrification. Through photography and video, she documents activities such as tenant-rights workshops and acts of public protest. Her role is not simply to bear witness, but to organize.

Interaction and collaboration is central to the project that de la Loza presents in “Talking into Action.” She and Eduardo Molinari both use research to engage in social movements. They visited one another in Los Angeles and Buenos Aires and participated in community action projects together. They also went on a lot of walks, inviting local activists to join them, and talk.

Of Molinari, de la Loza says: “We operate in different contexts, shaped by different political systems that hold different histories. But we also share a desire to gain a better understanding of the larger infrastructures that shape the societies in which we live; how knowledge can inform how we envision and work toward liberatory processes.”

De la Loza teaches visitors how to pick locks in a performance for her installation in Citizen Participant curated by Pilar Tompkins Rivas at Darb 1718 in Cairo, Egypt

Performance and installation view of The Art of Lockpicking, the Lockpicking of Art , 2010

Their multimedia installation includes visual, archival, sound, and text-based elements, and—as de la Loza describes it—functions as a “ritualized space.” The rituals are brujeria, witchcraft; and specifically, what she calls brujeria archivistica, a practice that reveals “obscured narratives and hidden ghosts” in historical material. The goal is to use ritual to purge the oppressions of history (and those of the present).

De la Loza has also begun a new project of her own, exploring the region around the confluence of the Los Angeles River and the Arroyo Seco, near where she grew up. She considers its history and ecology. She learns from local native people, and scours the landscape for signs of colonial impact on indigenous populations: the Spanish missionaries and later, the railroad tycoons, plying the American West. She notices abandoned railroad tracks, and considers the ruins of the “White City,” an exclusive 1890s resort community atop a peak in the San Gabriel mountains—a byproduct of the railroad boom and a symbol of exclusionism and greed. For de La Loza, the archive yields hidden ghosts like these, which she’ll expose to light.

All images courtesy of the artist.

See De la Loza’s work at Otis Ben Maltz Gallery, Talking to Action: Art, Pedagogy, and Activism in the Americas, 9/17–12/10/2017