“Sally Mann: A Thousand Crossings,” is a deeply satisfying survey exhibition of the photographer’s work which has traveled from the National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C. to the Peabody Essex Museum, Salem, Massachusetts and is currently at the Getty Museum in Los Angeles.

While attending the press opening, I had a chance to discuss the exhibition with the Curator of the National Gallery of Art. She wondered aloud why Sally Mann had not had a major traveling show up until this point in her career. Could it be that she was working from a region, the South, outside the art centers of Los Angeles and New York? Or, that her work was disparate in its interests, resisting a brand, and digital fashions? I wondered, if it were perhaps that there were few opportunities on this major museum level for any artist, and historically less so for women?

What was unexpected was the curatorial selection. Many of the photographs were being seen for the first time. The exhibition of 110 works has been organized into five sections entitled Family, The Land, Last Measure, Abide With Me, and What Remains.

Sally Mann’s career, and this exhibition, commences with what we first knew her for, the iconic photos of her family. This decade long series included photographs of her children, sometimes staged, and some of which were nude.

Sally Mann, Bloody Nose, 1991, Private collection

Image © Sally Mann

Much has been written about these photographs and Mann’s personal responsibility or lack thereof to her children, their welfare, as well as issues of child pornography. Historically tolerance and censorship ebbs and flows in cycles, governed by the prevailing moral politics of the moment. Looking back across two decades we wonder about the controversy and see the Art.

After the Immediate Family photos, Mann evolved to what she describes, as “deeply personal explorations of the landscape of the American South, the nature of mortality (and the mortality of nature), intimate depictions of my husband and the indelible marks that slavery left on the world surrounding me.” The exhibition’s next section Land is a preternatural view of the landscape in the South and the deep tensions it still holds.

Sally Mann, Deep South, Untitled (Bridge on Tallahatchie), 1998, Markel Corporate Art Collection, Image © Sally Mann

An image like Deep South, Untitled (Bridge on Tallahatchie) from 1998 seems to suggest something nostalgic, until you read the wall label that says this is the bridge from which Emmett Till’s murdered body was thrown. It is jarring, traumatic and ghostly, filled with the abject horror of this terrible American crime, yet deeply respectful.

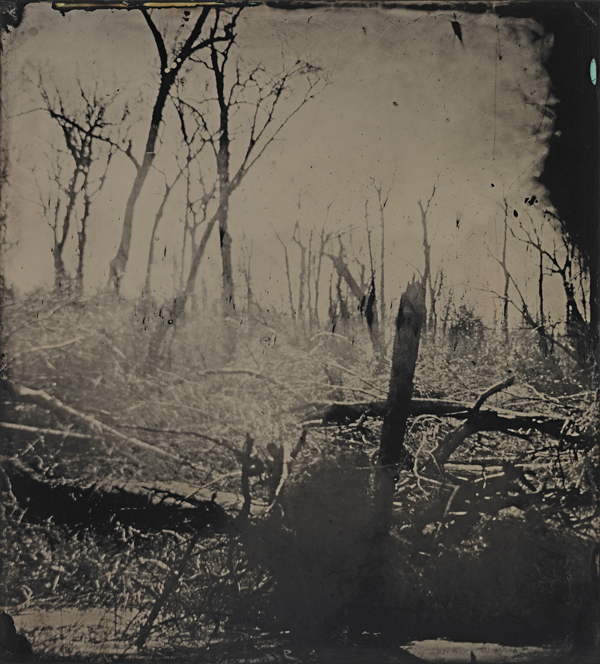

Sally Mann, Battlefields, Antietam (Black Sun), 2001, Edwynn Houk Gallery

The third section, Last Measure, large prints shot at the Civil War battlefields of Antietam are dark and mesmerizing. The point of view is that of perhaps a soldier, lying face down, bullets whizzing by, straining to see as the last light of reason flickers out in a blasted landscape. The work seems eerily prescient given our current growing disbelief in government institutions and growing social divides.

Sally Mann, Blackwater 13, 2008–2012, Collection of the artist

Image © Sally Mann

Her work is indebted to the South, and the history of blood and bones it carries deep within the body of the earth. Landscape for Mann is about the way place shapes people. In the fourth section Abide With Me, the artist seeks to come to terms with race, history, and the land as a contested site of struggle, survival, and shifting memories. Her Blackwater series of tin-types is brooding and visceral, photographed in the Great Dismal Swamp where Nat Turner and other fugitive slaves hid before the Civil War. The section continues with a room devoted to small photos of turn of the century African American Churches, when African-American’s were first free to worship without Whites overseeing them. The gallery is filled out with images of her parent’s African American housekeeper, Virginia. She was a clearly beloved figure for Mann, and how Mann first came to know the profound discrepancies and nature of race relations in the South.

Sally Mann, The Quality of the Affection, 2006, Private collection, Image © Sally Mann

The final section is called “What Remains,” and manifests her life long fascination with themes of mortality, death, decay, love and hope. This cycle of life and regeneration threads beautifully throughout the final section. It includes a photo series of her husband’s struggle with muscular dystrophy. (Insert image #25- The Quality of the Affection, 2006) She says of this work, “it began as documentarian and then became art, it makes weakness revelatory.” It was work she and her husband could do together, and were “incredibly happy times, lovely moments in their marriage.” They are still together. Sally Mann continues to live and work in Lexington, Virginia as she has for the past 45 years.

“Sally Mann: A Thousand Crossings” is on display at the Getty Museum from November 16 through February 10, 2019

A full review will appear in the March issue of Artillery