The term, “mindful awareness,” is a buzz phrase in current therapeutic and meditation circles (and, as I discovered a year or so ago, the institutional art world—or at least the Hammer Museum, by way of its alliance with UCLA’s Mindful Awareness Research Center). But a look back at the teaching practice and art of Corita Kent (1918–1986) almost makes you wonder if she invented it. Given what we know about her, she almost certainly would not have taken credit for such a paradigmatic, conceptual leap. She was far too modest, viewing herself in the context of her assigned role as a teacher in a religious community of women, specifically the Immaculate Heart order of nuns, itself subject to the authority of the Roman Catholic Church. Even after breaking away from her community and Church authority, she continued to see herself as a teacher first, fortunate to have seen her sideline blossom into a full-time occupation.

Against the backdrop of that social and professional context, she also clearly understood herself and her work as the product of a specific time and place, the “pixie-ish” (as described by many of her peers and family members), manifestly talented, but introspective daughter of a Midwestern family with a strong religious tradition, who came of age between two world wars and took her place as social changes began to unfold in the wake of American postwar, postindustrial prosperity. Her early career was a nimble improvisation within sharply circumscribed limits. By the time she began to gain a certain prominence at Immaculate Heart College, she was not unaccustomed to swift and somewhat abrupt changes and the occasionally odd juxtaposition; and you almost have to wonder if the formal and conceptual leaps of her career were borne out of a life that, between teaching and art, must have seemed a continuously unfolding experiment.

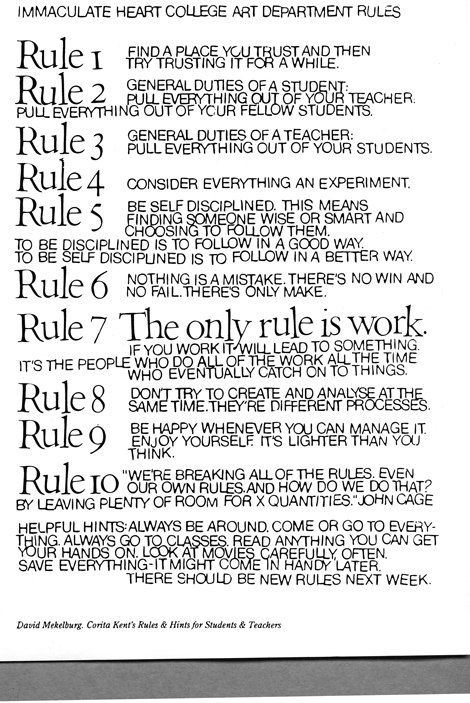

Immaculate Heart College Art Department Rules, created by Corita’s class, c. 1965, calligraphy by David Mekelburg, 1968 (IHC class of 1969)

Her famous “Immaculate Heart College Art Department Rules” (which took shape from conversations in the early 1960s among students and colleagues alike, including Barbara Loste, Richard Crawford and David Mekelburg, who designed and lettered the printed “Rules” in 1967) essentially describe her own modus operandi—the rules and precepts she crafted for a searching, inquiring and productive life. And not incidentally, a happy one: she made that leap of faith in the same way she cleaved to her religious faith— lightly. She was not unaware of what happiness contended with. Her chronic insomnia occasionally gave way to serious depression. There was plenty of struggle in Corita’s life. The rules are themselves a kind of quantum leap of faith—crafted with deliberation and sophistication. They are serious, but far from literal-minded, comprehending their own inversions and reversals. The last rule is that the rules will inevitably, even constantly, be broken. It’s a big, random universe, and exploding particles, quarks and black holes will open up beneath one’s feet so best to be open to (quoting John Cage, one of her intellectual mentors), “x quantities.” The cardinal rule remained the work ethic at the core of these commandments.

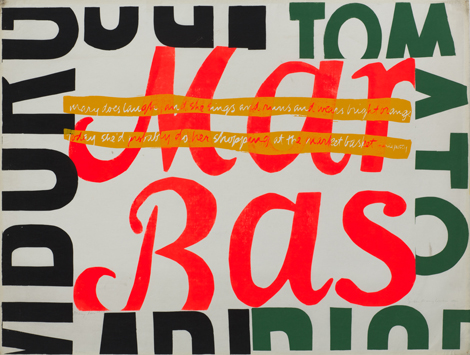

mary does laugh, 1964, private collection, photograph by Arthur Evans, courtesy of the Tang Museum at Skidmore College

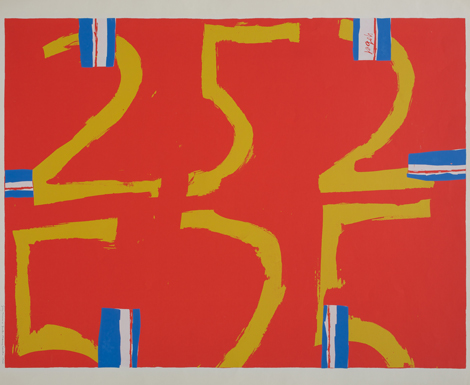

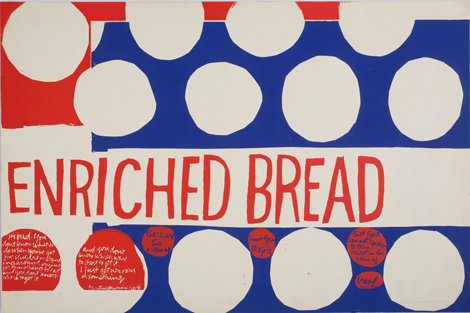

In her work ethic, she reminds us not a little of Andy Warhol, whose work she embraced early on. Under the tutelage of her graduate school advisors, her mentors within the IHM community, and the “great men” (and it was, alas, mostly men) she encountered in grad school and in teaching, she became a sophisticated observer of contemporary art. Her own artistic direction took shape fairly quickly between the mentorship of Alois Schardt at USC and Margaret Martin (or Sister Magdalen Mary, as she was known in the IHM community). Her early religious work reflects some of her first direct influences: the folk art she and Sister “Maggie” collected in New York and Europe, and the more expressionist range of the School of Paris style that dominated Christian religious art of that time. You see the influence of Rouault (or what Corita referred to as “Byzantine”), as well as a bit of Motherwell, in some of these early productions, but always with a difference. The tendency to abstraction—from expressionism to color field to something still more bold and radical—is there from the start. Her earlier enthusiasms in the New York School included Motherwell, Rothko, Milton Avery and—less abstractly, but clearly in synch with the liberation theology adopted by so many of her religious peers, Ben Shahn. She latched onto Pop early, though also with a view to adapting it to a didactic, social, philosophical and religious agenda. Yet—always attuned to the inversion, the reversal—she embraced words and letters as abstractions in their own right.

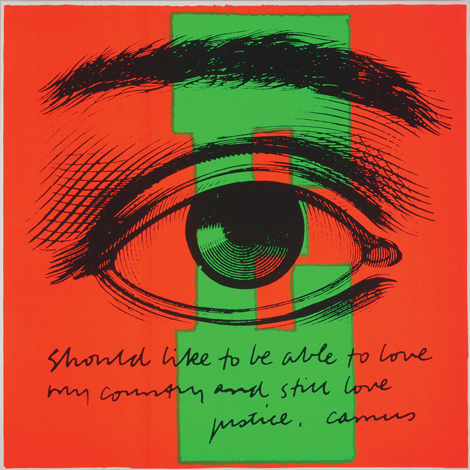

If the didactic, quasi-utilitarian aspect of some of Corita’s art diminishes its appeal, she would probably argue that religious or at least spiritual advocacy was its intended value. She is frank about making a religious art; but the faith expressed in many of the texts is strikingly nondenominational. “She did not have a conventional approach to faith,” says biographer April Dammann. “She was always ecumenical.” Many of the texts leave space (literally and figuratively) for ambiguity, irony, even doubt. Darkness as well as sunlight frames these clouds of thought—but the sunlight dominates. “I was trying to make [quote-unquote] ‘religious art’ that would be not quite as repulsive as what was around,” she said in 1976 interviews that form part of an oral history prepared by UCLA archivist Bernard Galm. But she adds, “Pretty soon I realized that anything that was any good had a religious quality, so that it didn’t matter whether it had that kind of subject.” Her best work transcends any specifically doctrinal content (which is usually slender). Far more common is a dialectical, even interrogative, text-heavy visual counterpoint of vibrant primaries and secondaries that occasionally modulate into deeper hues or pale washes. She exploited the silkscreen process brilliantly to achieve the desired chromatic effects.

that they may have life, 1964, collection of Siri Gopal Singh, photograph by Arthur Evans, courtesy of the Tang Museum at Skidmore College

She is clearly intent on creating poetry, even drama in these works; but this is a functional art. “The idea of the function of an object was appealing to Corita… another approach to breaking down barriers between what is art and what is not art; that art was everything and should be everywhere,” comments Ray Smith, director of the Corita Art Center. “Functionality is obviously at the core of design and industrial design in a way that doesn’t exist in fine art approaches.” Discussing the IHC “Rules” and the rule-breaking they necessitated, Michael Duncan, co-curator of “Someday Is Now: The Art of Corita Kent” (running through Nov. 1) exhibition at the Pasadena Museum of California Art and Corita expert, reminds me of the Balinese saying she was fond of quoting: “We have no art. We do everything the best we can.”

As Corita’s embrace of craft, folk and commercial art indicated, she saw most art and design existing on the same aesthetic continuum. No doubt influenced by the mentorship of designers like Charles and Ray Eames, she was not reticent about engaging commercial and industrial design, or for that matter enlisting her students in projects commissioned by private corporations and institutions that would ultimately enrich the College and their department. Her approach was broadly creative, rather than strictly formalist: she worked with what was all around her and immediately available (beauty was not necessarily an essential criterion, though a desirable end). She was turning Pop and appropriationist strategies to her own ends in creating a mass art; and she took her students along for the ride. But this was what most of her students had signed up for.

“Applied practice was what they were teaching; it wasn’t ‘art school’ in the sense that we have today,” Ray Smith reminded me. “Many of Corita’s students went on to be commercial artists and many went on to other professions carrying the mantra of doing everything as well as they can. I have heard some of them say they didn’t become an artist but whatever they do, they do it artistically.”

E eye love, 1968, collection of Corita Art Center, Immaculate Heart Community, Los Angeles, photograph by Arthur Evans, courtesy of the Tang Museum at Skidmore College

Corita was crafting a mass, message-oriented art, but, as Duncan underscored, a sophisticated one, free of “finger-pointing” or obvious “agit-prop” tactics. Corita wasn’t afraid of complexity. Smith, Duncan and Damman all remind me that an English or literature minor was a pre-existing requirement for art department admission at IHC. “They were giving students a grasp of literature and poetry; teaching critical thinking,” says Duncan. “Corita’s stealing back the messages of advertising, …” and empowering the hapless consumer.

There were also parallels between Corita’s chosen medium and her teaching methodology. “Print is a very process-oriented medium, created one layer at a time; printing a layer 100 times …each successive layer buildings upon the next; and as a teaching nun, she was accustomed to process and routine, following an order,” says Smith reflectively. Corita was capable of taking that process orientation to an extreme—all to a point. “Corita was notorious for her quantity and process assignments. Not only did she make assignments like, ‘look at a tree for one hour, make 10 drawings and then select a section of each of those drawings and make 10 more,’ the assignments built on each other. Students might be instructed to pick out pictures from a magazine, then reinterpret those photographs as watercolors, then make collages from those watercolors; and so on.”

Duncan laughs about some of the video documentation of Corita at work with her students. “You see her in class telling her students, ‘ I want you to make 100 collages this weekend. By number 60, you’ll be doing something I want to look at.’” Another former student’s family members talk about an assignment to make 20 puppets with a scenario crafted around them—“the weekend we went crazy making those puppets.”

mary does laugh, 1964, private collection, photograph by Arthur Evans, courtesy of the Tang Museum at Skidmore College

“As they became more and more desperate, they started breaking the rules,” just as Corita intended. “They’d camp out weekends on the campus, sleep over, to finish these over-the-top homework assignments,” Dammann recounts. “She’d screen a short Charles Eames movie and tell the students to write 500 questions they wanted answered about the movie…. At a certain point, you get to a state where your mind frees up and creativity can happen.”

“Let a thousand flowers bloom”—or a thousand art collectives. Corita expected that her students would inevitably draw from each other and work collectively with other students, friends and family—consistent with “Rule 2’s” mandate to “pull everything out of your fellow students.” She was as intent on pulling breakthroughs from her students as she was from her own art. “There should be new rules next week,” Corita teases in the pendant advisory, only half tongue-in-cheek. The breakthroughs continued pouring from her randomly, routinely, even processionally. She turned the school’s annual signature religious pageant into a proto-happening or “be-in,” essentially on a dare; an art of “radical juxtaposition” was simply a logical next step and not at all out of line with prevailing ecclesiastical authority. The local ecclesiastical authority (the Los Angeles archbishop, Cardinal McIntyre) was a different matter; pressures on her would eventually push her out of the College and away from her religious community. For Duncan, the style, rigor and spirit of the IHC art department in the decade between 1958 and 1968 made it de facto one of the country’s top art schools. It was a spirit that carried on until well into the early 1970s, according to, among others, LA artist Carole Caroompas, who taught there at the time. By that time, riding the crest of Corita’s legacy, the school attracted a a pool of wildly creative students. (The late designer, Gregory Poe, and Artillery’s own Skot Armstrong, were students.)

“Save everything,” Corita writes in that postscript to the Rules. She’s talking about life experience as much as materials. Her pedagogy, like her art, was a kind of bricolage, albeit a rigorously contextualized, examined and continuously refined one. There’s ceremony and celebration in it.