Victorian critic Walter Pater’s famous maxim that “all art constantly aspires towards the condition of music” admires the musician for her destruction of boundaries: “[Music’s] end is not distinct from the means, the form from the matter, the subject from the expression; they inhere in and completely saturate each other.”

I have always read Pater as meaning that music’s dissolution of formal categories also denotes its dismantling of borders within the listener. Music can trigger heightened emotions—ecstasy , lust, and anger. When people share these states in public, say at a concert, the experience creates opportunities for new ways of engaging with community.

That the Broad Museum has made music a central part of its four-episode Summer Happenings, then, proves something to celebrate. Museums are paradoxes: They are filled with subversive messages and yet confront the patron with a rash of regulations, usually requiring us (with the promise of violent correction by a nearby guard) to refrain from touching, yelling, running, crying, sitting down randomly on the ground, or expressing erotic desire, even while we commune in the presence of art—say, Kara Walker’s incendiary silhouettes or Cindy Sherman’s portrayal of abjection—that would inspire volcanic reactions in other settings. Museum culture requires its patrons to dither about politely in the face of these stimuli, which makes it a queasy exercise in social conditioning: You are being taught to obey the rules of wealthy establishments even as you absorb artists’ often insurrectionist cris de coeur about social injustice. At its worst, this institutional practice cultivates generations of docile bystanders.

The Broad has now held three out of its four Happenings (the last is on September 24), and each one featured a sound-enhanced occasion for observers to shed their inhibitions. At the first Happening, Perfume Genius put on a heart-thrashing concert in its plaza, and at the second, Brontez Purnell inspired people to run madly around its lobby to a chilling Ronald Reagan soundtrack. In so doing, the Broad’s art and space “saturate[d] each other,” that is, guest curators Bradford Nordeen, Brandon Stosuy and Director of Audience Engagement Ed Patuto expanded the rules of permissible behavior on its moneyed campus.

Macy Rodman

The Broad’s Third Happening also provided exciting chances for people to feel something real together, particularly when Macy Rodman took the small stage in the Broad’s Oculus Room. Rodman is perhaps best known for her 2016 anti-bashing music track Violent Young Men (“they want to rip out my eyes and tear off my skin”). Her performance on Saturday, August 20, proved cathartic, as she banshee-wailed songs about love lost.

Macy Rodman

Most audience members sat on the floor, shouting in recognition as Rodman appeared in a blue negligee while ululating Cher’s 1998 hit Do You Believe in Life After Love? She rolled around on her stomach, rasping “Oh I don’t need you anymore/I don’t need you anymore,” as if trying to convince herself. She next scorched the crowd with Stevie Nicks’ Landslide, screaming “I’ve been afraid of changing/’Cause I’ve built my life around you.” The audience’s empathy rolled off their bodies in waves as they sang along, creating an electric, anything-is-possible sensation that lifted the Broad from the status of luxury warehouse and into a site of generativity.

Sparkle Division

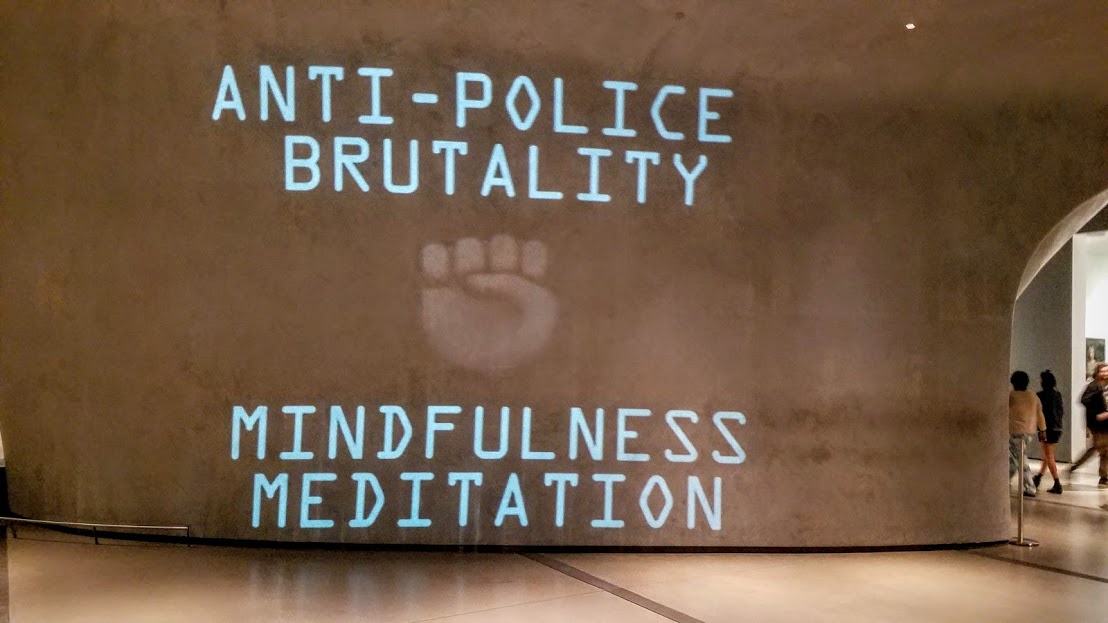

Throughout the evening, Tabita Rezaire’s video showing anti-police brutality messages and yoga imagery played in the lobby. The ambient-sound sax act Sparkle Division and the pop art singer-songwriter Rostam also filled the plaza with good tunes.

Rostam

But, besides Rodman, the most notable event also took place in the Oculus venue, which hosted the Footwork music visionary Jlin. Footwork is complex, sample-heavy dance music that came out of Chicago in the late 2000’s, and Jlin has innovated an originalist’s take free of borrowing. When Happeners first showed up at the Oculus, we were told that we could not sit during Jlin’s performance, and so we stood around swaying shyly as she alchemized a mesmerizing series of heavy beats and repeated alarms. As I looked around, I noticed a light crowd that seemed unsure how to move to her music. This is perhaps because Footwork encourages dancers’ rapid steps and skillful agility.

Jlin

But I also observed the racial composition of the Broad Happening audiences, which could have been more diverse. I also didn’t see any disabled people, who could feel excluded by the stand-only policy. When I poked my head out of the room, I saw most folks frolicked outside, drinking and chatting as if at a fashionable party. The Broad’s plaza hosts very little seating, except for a few wooden stools, and a lot of Happeners undulated around the bar on their expensive-looking stilettos or creepers. As in the rest of society, invisible boundaries existed everywhere.

The Broad’s curators are creating settings for a new and rousing engagement: Emotional expression is not distinct from the museum; gender can be fluid; Chicago inheres in L.A. But they can enhance inclusivity: Tickets are $35; the set-up is disability hostile. Instead, price tickets on a sliding scale and make the space more accessible. Do outreach. In this way, the Broad’s encouragement of shared transcendence can reach a greater range of people, and its message can take on more weight.

Perhaps all art aspires to the conditions of music. And all art institutions should aspire to the conditions of community.

Photos by Ryan Botev