This exhibition is simply horrible: a catalog of horrors, a parade of barbarism made all the more wretched because we have become inured to atrocity, our attention spans irredeemably vaporous. It is both commonplace and theatrical, a fleetingly addictive entertainment. For this particular presentation, Rodney McMillian is our impresario of the Grand Guignol: he presents for all-comers. Most viewers will consider themselves informed after viewing such provocative work and refer to it conversationally, while others might nod. For a very small minority of patrons, however, the horror remains and resonates long after leaving the exhibition because, for them, it is a wound that never heals.

McMillian has traditionally considered race in his varied works—abstraction, installation, video, sculpture—and those works are incisive and dolefully contemplative, but this exhibition, symptomatically titled “Body Politic,” is rawly unmediated. It seethes. There is revulsion, there is contempt, there is distrust, and nothing is held back.

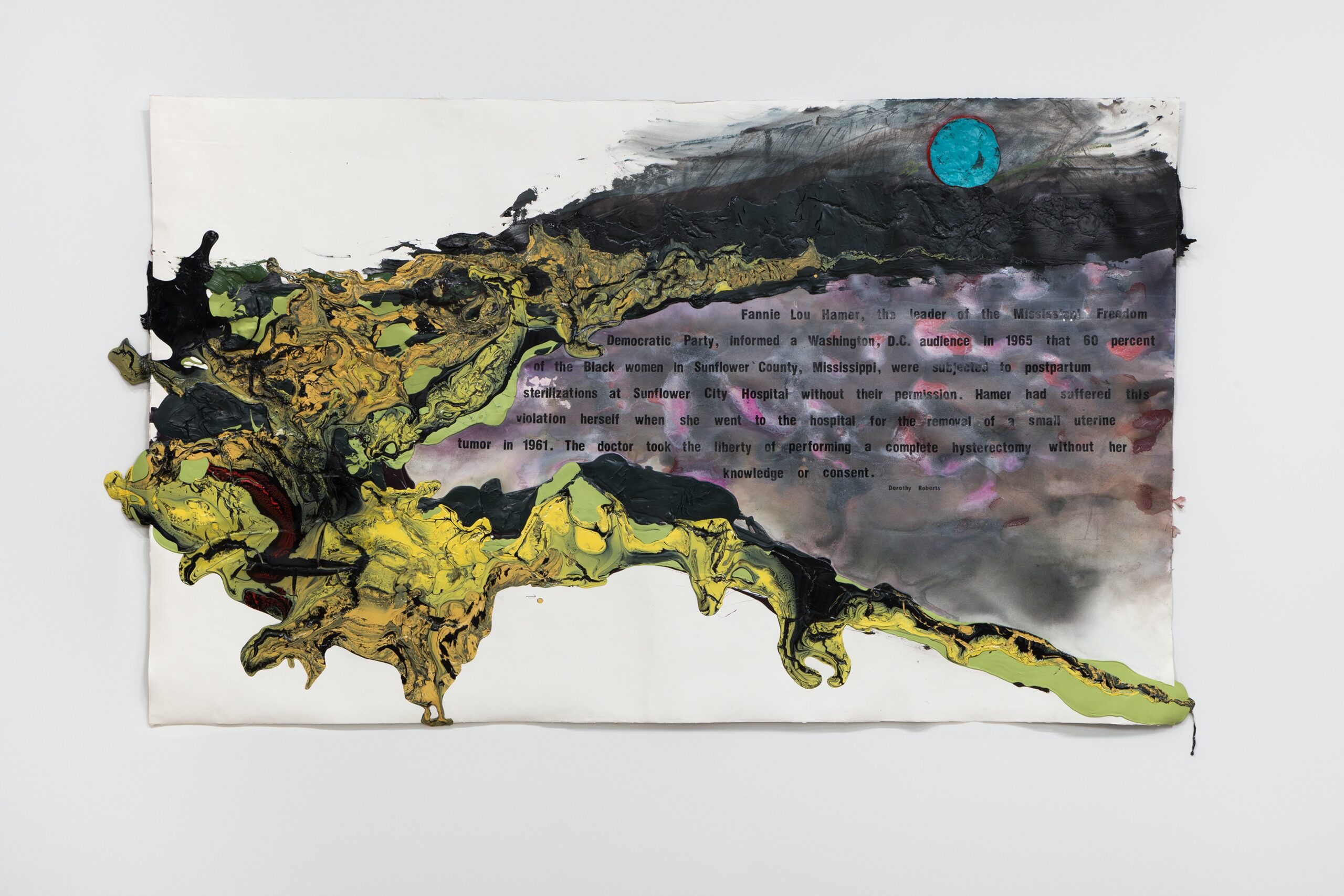

Many of the paintings include text—shakily lettered and slashed with color—and nonchalantly recite atrocities committed upon Black bodies. These are works of anger and disgust but it is the works done in all black—mute and imperious Rorschachs— recite that are most arresting and lastingly communicative.

Rodney McMillian, Mississippi Appendectomy,”2020. Courtesy of the artist and Vielmetter Los Angeles. Photo by Brica Wilcox.

Cell I (2017–20) a crushed smoky butterfly, and Cell II (2018–20) a broken crystal, are dense matte black schematics that swallow light. They suggest both architectural plans of secret and forbidden locations; sites where inhuman actions are performed, and human biological cells, polygons of our very humanness laid out and schematized. It is in these suggestive fragments, both as visibly microscopic and structurally fabricated, that McMillian excavates the cornerstone of American history with an appetite for the ruination of Black bodies, minds, economies and futures.

Similarly harrowing, but extruded and eerily present are Untitled (Heart) (2018-19), Untitled (Entrails) (2019–20 )and Black Dick (2017–20), all configured of fabric, chicken wire and historical taint. Heart, a crumpled valve coarsely folded in upon itself, suggests not only a statistical report on racial disparities of life expectancy but the daily uptick in heart rate at the near-daily suspicions and discourtesies regularly encountered. Entrails is a snare, a serpent and long tether that harnesses and binds in employment, advancement and trust. Black Dick is a dehumanization, a fetishization, and with apologies to the BBC, a traditional lynching souvenir.

There is a rage in this exhibition but few will become enraged by it. Only those very few, that small segment of the population for whom this exhibition is a historical ID card.

And if you are of the mind that “You people should just get over it, that was so long ago” try remembering an earthen dam in Mississippi and three dead civil rights workers with upstanding citizens looking down at their murdered bodies, then recall a street in Minneapolis.