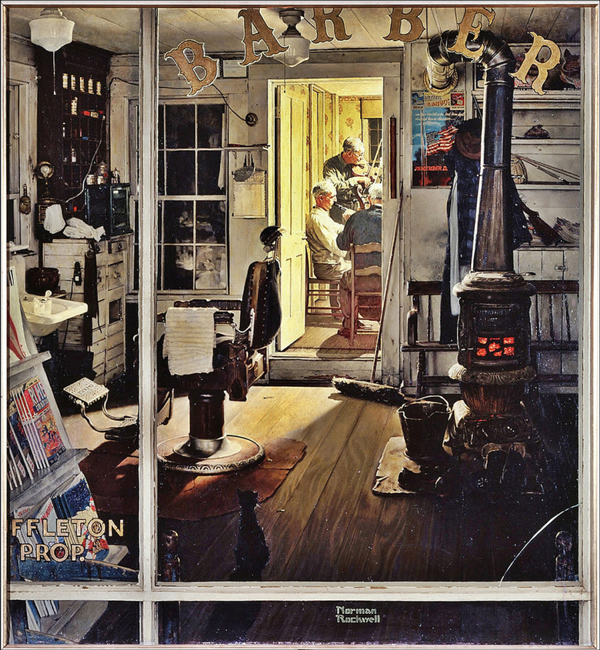

Although I’m not a big fan of Norman Rockwell’s artwork, a painting of his caught my eye after becoming the centerpiece of a controversy that has rocked the art world. Rockwell, the longtime cover illustrator of the Saturday Evening Post working from the 1920s to the 1960s, was known for producing images of daily American life—rosy-cheeked folks in church or kids playing baseball—a cornpone vision of America ensconced safely behind white picket fences. The Rockwell artwork at issue, Shuffleton’s Barbershop (1950), is part of the fine art collection of the little-known Berkshire Museum in Pittsfield, Massachusetts, which announced in July 2017, that it would auction the painting. Rockwell meticulously reproduced the myriad details of Shuffleton’s barbershop, but what fixates the eye is the back room of the shop in which an elderly group of men are playing musical instruments bathed in a rich inner light matching the glow from a wood-burning stove. The painting would fit into the oeuvre of a Dutch master, perhaps Jan Steen.

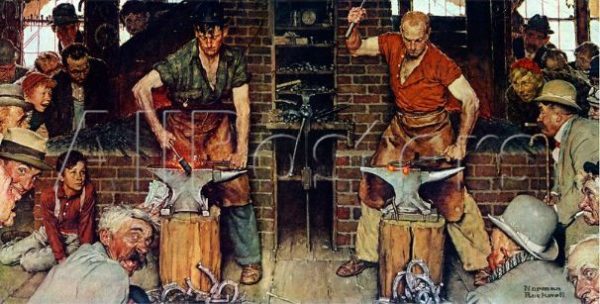

Shuffleton and an additional Rockwell, Blacksmith’s Boy—Heel and Toe (1940), were among 40 works, including those of Hudson River School artists Albert Bierstadt and Frederic Church, which the Berkshire Museum intended to deaccession and sell at auction. The museum, founded in 1903, claimed that it was operating at a significant deficit for years and intended to use the auction proceeds for general operating expenses and construction – a controversial practice strongly frowned upon by the two major American museum associations.

The museum declared that all of the works put up for auction were “unrestricted and unencumbered” gifts. This statement did not stop the Rockwell heirs, who claimed their father had restricted any sale of his bequest, from publicly denouncing the museum’s plan and taking legal action to halt the sale set for Sotheby’s November 2017, New York auction.

Norman Rockwell, Blacksmith’s Boy—Heel and Toe, 1940

Writing in the Berkshire Eagle, Joseph Thompson, the director of Mass MoCA, the most important museum in western Massachusetts, defended the decision of the Berkshire Museum, claiming that it faced a crisis and needed the money to focus on its core collection of thousands of scientific and natural history artifacts, instead of its relatively small art collection. But Thompson pointed out that the population of the region has declined dramatically in recent years, as has corporate giving, and that even the estimated $40 million the Rockwells alone might realize would not fill the hole the museum had dug itself into.

The Norman Rockwell Museum is nearby in Stockbridge, Mass, where Rockwell lived and it might be reasonable for the Berkshire Museum to simply face reality and close its doors while dispersing its collection to other museums. Auctioning these paintings exposes them to a fate which has claimed thousands of world-class artworks purchased by the super-rich—all too often hidden away in fireproof vaults of the freeports in Geneva or Singapore.

I spoke with David C. Levy, the former director of the Corcoran Museum in Washington, D.C., who told me that an art institution that sells its core assets for general funds or construction may be violating the guidelines of the Association of Art Museum Directors and the American Alliance of Museums. Museums that ignore the associations’ rules risk having their accreditation suspended or revoked. Levy said that a museum can sell unencumbered artworks to help fill a gap in its collection, or sell a group of an artist’s lesser works to purchase a superior work by the same artist. Additionally, a museum can raise general funds by selling non-core assets. He gave as an example his orchestrating of the Corcoran’s sale of a quartet of Stradivarius instruments, including a rare viola, which raised millions for its main mission of supporting its extensive fine art collection.

Under Levy’s logic the Berkshire might insist that the 40 artworks it intended to sell was not its core collection, and instead claim that designation for its fossils and arrowheads, but that might not pass the test.

Last October, the Rockwell children filed suit in Massachusetts asking for a temporary restraining order to halt the Sotheby’s sale on grounds that it violated the museum’s charter and that the board violated its fiduciary duty. They joined the state attorney general as a necessary party because that office oversees the activities of charitable institutions.

In a press release responding to the lawsuit, the Berkshire Museum stated that the board of trustees “fulfilled its fiduciary duty… to address urgent and serious financial challenges threatening the future of the museum by developing a new vision for the museum and funding to support that plan. The museum’s community wanted not simply another display of fine art, but an institution that would engage them with a greater emphasis on science and history.”

On November 10, 2017, the Massachusetts Court of Appeals granted a restraining order halting the sale of the Rockwells or any of the Berkshire’s works at the planned auction. The Massachusetts attorney general sided with the heirs stating, “This sale is unprecedented in terms of the number, value and prominence of the works being proposed, the centrality of these works to the museum’s collection, and the process the museum employed to select and dispose of the deaccessioned items.”

Most significantly, the appeals court ruled that there were conditions attached to some of the bequests of artworks, especially by Rockwell, who had received assurances from the museum that his works would remain in its permanent collection.

Ironically, if the court ultimately lifts the restraining order, the recent notoriety of the two Rockwell works is likely to attract fierce bidding and drive up the hammer prices at auction.