Capturing human dignity through drawing requires commitment not only to clearly see but to deeply observe. Current works by Richard Wyatt Jr. at Steve Turner gallery encapsulates such an act. As a muralist in the tradition of such predecessors as Charles White, John Biggers and Hale Woodruff, the Los Angeles-based Wyatt is no stranger to portraying humanity with proficiency and sensitivity. The Capitol Records building, Watts Towers Art Center and Ontario International Airport all testify to the caliber of Wyatt’s public art.

Yet this current exhibition of pencil, charcoal and graphite works on paper places him in a much-deserved category of his own within an art canon that tends to consistently ignore some while invariably celebrating the same individuals. In fact, just as John Coltrane revolutionized the saxophone into an instrument never heard before, Wyatt’s heightened vision coupled with expert eye and hand coordination transforms a surface with abstract lines and marks as if playing A Love Supreme (1964) on paper.

Glory Cloud (2019), for example, introduces Wyatt’s father at age 88. In a society that glorifies the notion of permanent youth, this work dismantles such a destructive obsession. Portrayed as if stepping out of the sky, this realistic yet interpretive rendering differentiates shirt texture from skin surface, suitcoat from mustache and beard, hands with veins from suitcoat with buttons. Moreover, his penetrating stare suggests that wisdom comes with age. Like Dean Mitchell’s watercolor portrayal of an older African American male in For Freedom (2020) and Carolyn Lawrence’s acrylic work, Pops (1970), Wyatt accomplishes the same; he captures the essence of the human experience. Additionally, within the context of a 21st-century global pandemic that ravaged African Americans and the elderly, this personal aesthetic choice is socially conscious and timely.

Richard Wyatt Jr, Installation view, 2021. Courtesy Steve Turner.

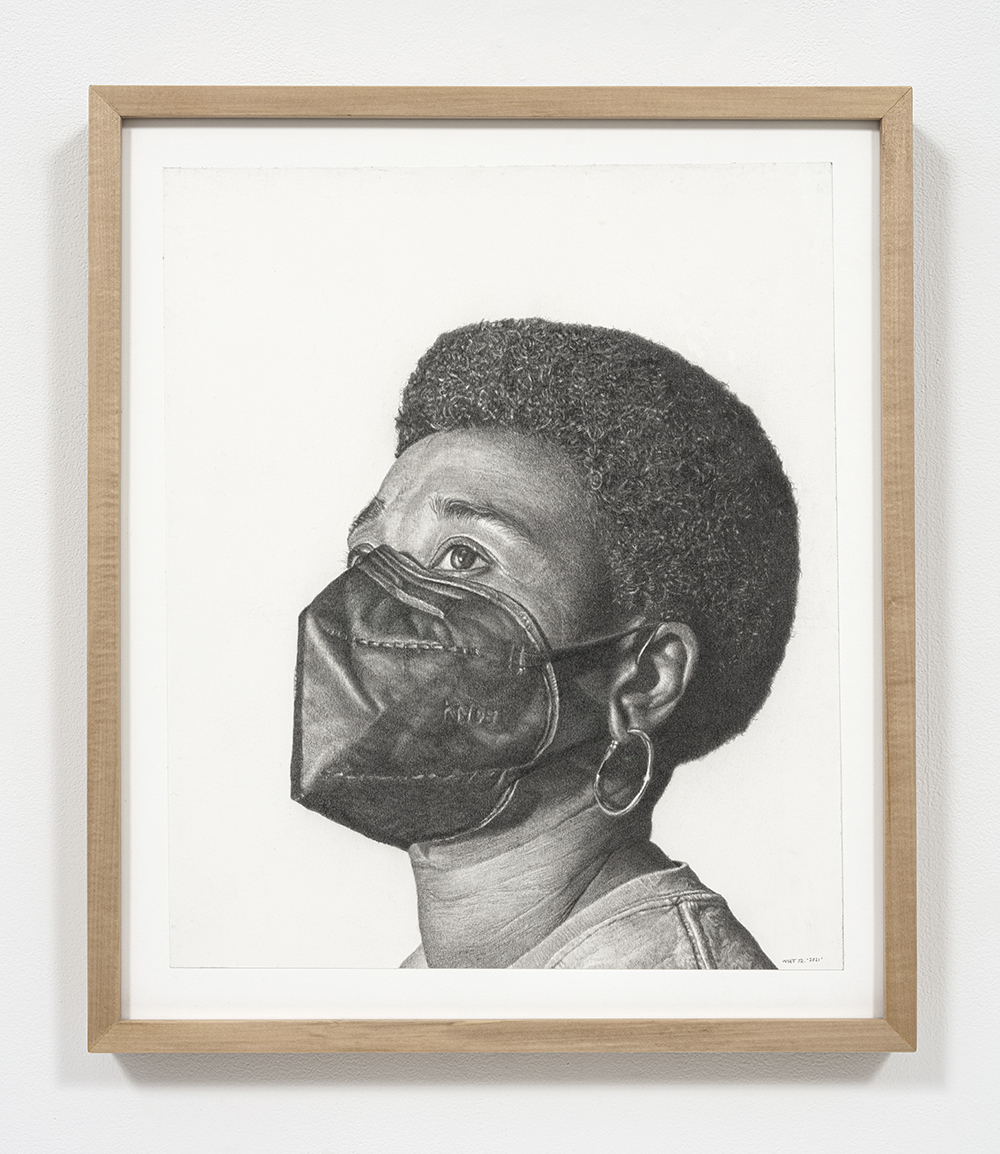

Road to Recovery (2021) and The Gifted One (2021) show Wyatt’s ability to expand the boundaries of the Photo-Realism movement of the 1960s and 1970s. The former image is a graphite portrait of his daughter wearing a face mask, demonstrating the tenderness of Wyatt’s application of chiaroscuro. With a three-quarter view, her eyes anticipate a hopeful future. The latter is a timeless charcoal snapshot of the late NBA great, Kobe Bryant. A first reading of both images reveal Wyatt’s skill at capturing the nuances of skin texture.

Finally, there is Joyce, (2021) in which Wyatt’s rendition of his wife of 43 years demonstrates his advanced skill at portraiture regarding facial features, proportions, and shadow contrast. Starting with the hair and then to the earrings and to her glasses, this image breathes life; he captures the look of love as her eyes suggest the value of memory. Each intricate pencil mark and suggestive contour line communicates an uplifting message to his wife, family and community.

Ultimately, “Loss, Healing & Restoration,” accomplishes what is implied by the title—acknowledgement of pain with a single-minded focus on transformation. A visual historian of his community, Wyatt’s works reinforce the sacred interconnection to others.