Since its invention, the camera has often acted as an intruder, an interloper or an uninvited guest. Walker Evans photographed subway riders from a camera hidden in his coat. His black-and-white images depict men and women gazing at the camera while immersed in their own thoughts, unaware that they were being photographed. Evans engaged in this act of surveillance before it was embraced by artists. Since Evans, numerous artists and photographers have captured their subjects unaware. In the 1990s in lower Manhattan Merry Alpern photographed people engaged in various sex acts, pointing her camera out the window from a building across an alley. John Schabel used a telephoto lens to capture passengers in windows of departing airplanes. Now people assume surveillance cameras follow them in public spaces. While most don’t like that we are watched, it is a fact of contemporary culture and not often challenged.

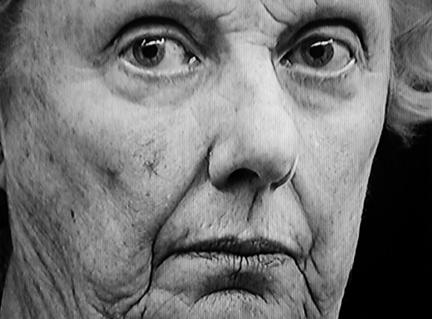

In his exhibition entitled “Eyes Words,” Richard Kraft has created a series of voyeuristic (video) snapshots that take cues from Evans’ project. While traveling on the London Tube, Kraft captured footage of fellow passengers by using a hidden video camera. While Evans, Alpern and even Schabel’s images depict location, Kraft has cropped his photographs to remove any reference to place, focusing instead on gaze and expression. Isolated, anonymous faces fill the frames. Enlarged to almost six feet wide, and completely desaturated, the crispness of the pictures dissolve and meld with the vertical screen lines imported from the original videos. Face and screen become one. Basic facts of these travelers’ journeys become less important than their vacant stares and blank, zombie-like expressions. In surveillance footage one image replaces another, erasing what came before; here, Kraft carefully preserves these “lost” moments.

In contrast to these seven enlarged portraits, Kraft also presents a grid of 100 stamp-sized video stills offering multiple views of the same person. But several nuanced expressions offer no more insight. The grid of small images, each floating in a large white matte, suggests the passage of time and the insignificance of the individual.

As for the second half of the exhibition’s title, the central space of the gallery supports three of Kraft’s word collages. Ulysses (2012) the largest of the three, is a work on paper in which James Joyce’s novel has been cut into small pieces and reassembled. Each triangular shaped text offers a poetic snippet from the original. Joyce’s book is a daunting read, but Kraft’s re-presentation makes reading in the traditional manner impossible. The montage of words produces random associations and a yearning to connect a part to the whole.

Clearly, Kraft’s exhibition of Tube portraits is an exercise in editing. His choices are specific, as he selects only isolated individuals who communicate a certain kind of grim blankness. No one appears happy or sociable. In his word collages he explores a different kind of editing that parallels the lack of individuality in the portraits. Using all the supplied text, he carefully arranges its placement, somehow obscuring any references to proper names.