“Revolution and Ritual,” while very narrowly focused on three Mexican women photographers, seeks to address in broad strokes changes in ideas about Mexican identity through the work of Sara Castrejón, Graciela Iturbide and Tatiana Parcero, whose careers together span more than a century.

Castrejón, a studio photographer-turned-war documentarian, began photographing the various revolutionary factions as they traveled through her home town of Teloloapan in the state of Guerrero during the Mexican revolution. Her photographs, all postcard-sized—a facet of the economics of the studio photography of that era—are displayed within a quadrangle of walls and vitrines in the center of the gallery, as if in a time capsule. The works are interesting for what they convey about social strata; for example, her portraits of soldiers from indigenous areas who have been pressed into service by one faction or another, or that of Colonel Amparo Salgado (Sin título, 1911), a woman who led soldiers into battle. While many of Castrejón’s subjects adopt stilted poses, Salgado stands with a remarkable grace and self-assurance, her matter-of-fact gaze conveying a kind of unaffected, seen-it-all confidence. A few photographs hint at the violence that tore through the country: troops in front of a building pockmarked with bullet holes (Sin título,1912), an execution (Sin título,1913), and three very young revolutionaries awaiting the firing squad (Sin título,1913).

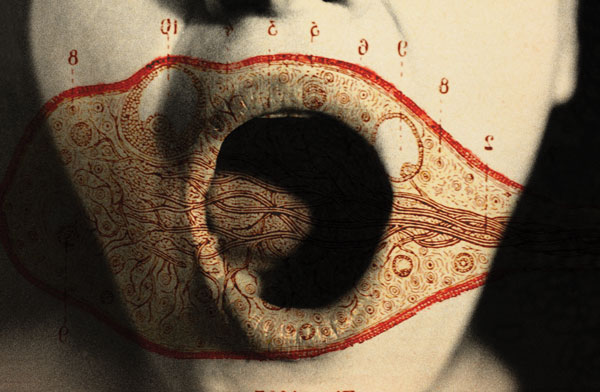

Cartografía interior #21 from the series “Cartografía interior” 1995-1996, courtesy Scripps College, Ruth Chandler Williamson Gallery.

Iturbide’s photographs are a real visual feast and the most immediately engaging of the exhibit. Encouraged by her mentor Manuel Álvarez Bravo, the preeminent Mexican modernist photographer, Iturbide used photography as a means to explore her country. Her depictions of indigenous communities and rituals that held both pre- and post-Conquest significance convey a sensitivity and sophistication that permeates her work. Virgen de Guadalupe, Chalma, México (2007) depicts a large radiant mandorla from which the likeness of the Virgin is missing. The absent body evokes both a pre-Columbian past, in which the Nahua fertility goddess was enshrined, and the Spanish colonial substitution of the Christian symbol. Mujer Ángel, Desierto de Sonora, México (1979) also confuses epochs with a Seris Indian woman dressed as if from a different century, holding a 1970s boom-box at her side.

The mixed-photographic media works of Tatiana Parcero employ images from pre-Columbian and European maps and codices, biological drawings, and even diagrams from esoteric or mystical systems paired with truncated photos of Parcero’s own body printed on transparent acetate as a means to address the violence of conquest, and the many disappeared bodies both in her country of origin, Mexico, and Argentina, where she now lives. Her “Cartografía Interior” series, full of biological drawings, suggests lost bodies of knowledge and an unknowable interior; the “Nuevo Mundo” series, featuring various world maps overlaid with images of her pregnant body reiterates the magnitude of European conquest and concerns of lost identities. The recurrence of violence through various social and political upheavals, the suppression of cultural identity, and the colonization and disappearances of bodies is a theme that runs throughout Parcero’s work and unifies the exhibition as a whole.