I was sitting in my car when I heard that Lou Reed had died. The announcer went on to say that although Reed was not as famous as the Beatles or the Eagles, blah, blah—I almost rear end the car in front of me. Not as famous as the milquetoast-I-Wanna-Hold-Your-Hand Beatles? And then this dork doesn’t even mention Reed’s song, “Heroin.” I mean what would you rather do, hold her hand or wait for the man? I thought about getting out of the car and holding up one of those twirly signs saying, “Lou Reed’s song ‘Heroin’ is New York’s answer to Jim Morrison’s song ‘The End.’ You can’t get any more famous than that.” But I didn’t because the radio is right: Plastic is more famous than platinum and mercury is far more dangerous than a styrofoam eagle. Heroin, it’s my wife and it’s my life. It echoes through my skull, both dangerous, sad and beautiful. So after my little mental rupture I continued driving home, but something is fucked up.

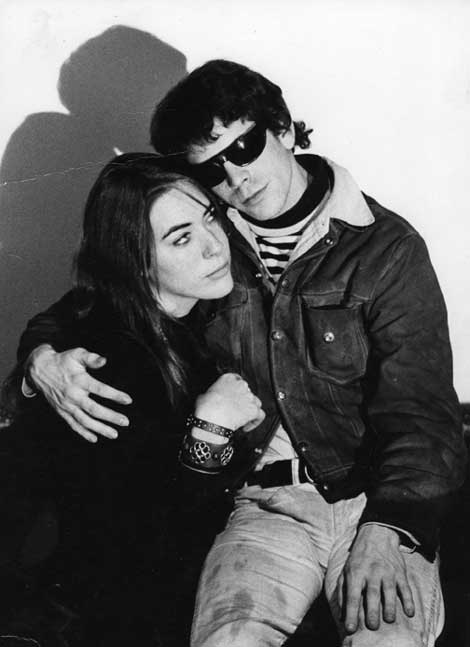

Mary Woronov and The Velvets and Andy Warhol, circa 1967, photographer unknown, courtesy Mary Woronov

People hated them. We loved them. Maybe in the beginning, the Velvets wanted to offend and disturb their audience but then entertainment was not high on our list either. After all, Warhol’s movies were anything but entertainment. We were all waiting for something a little darker to come crawling up the stairs and maybe even halfway down the hallway if we were lucky and this band fit right in. They were sort of with us from then on—next thing I knew they were a major force.

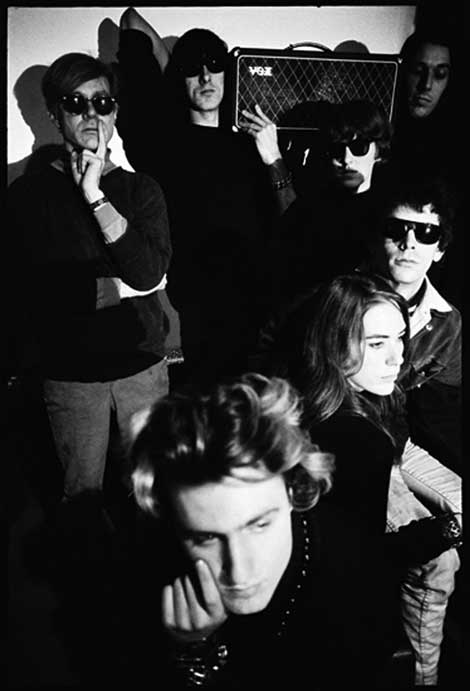

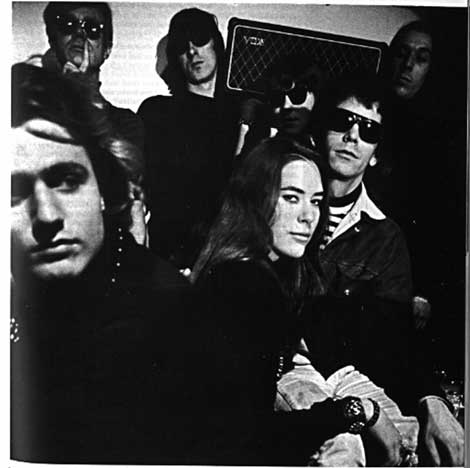

Mary Woronov and The Velvets and Andy Warhol, circa 1967, photographer unknown, courtesy Mary Woronov

It took me a whole book to say that—I wish I knew both Andy and Lou better, I wish I hadn’t been in such a hurry to race through the best time of my life.