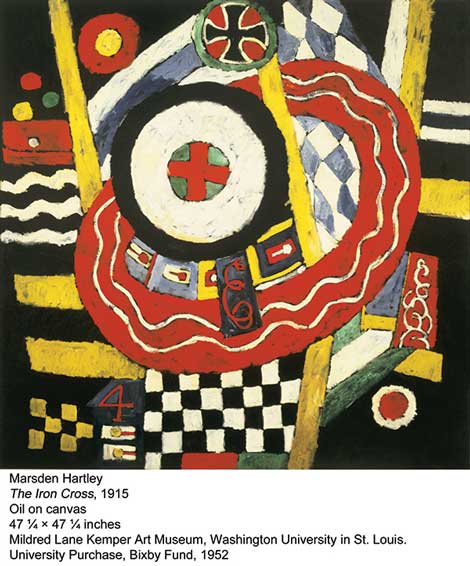

A lover of Marsden Hartley’s landscapes, especially the “Dogtown” series, I have never been interested in his so-called cubist series depicting German symbols. Why would someone who could paint the mystical rhythms of Dogtown or the insane colors of the Mexican desert be interested in a fad involving a square? Luckily, this past summer’s LACMA exhibition of Hartley’s early work (Berlin period, 1913–15) showed no sad rehashing of the cubist failure, Instead, the energy and frenzy of his paint describe the ordered excitement of a nation blindly following the symbols and hype of war, and the churning gears of an unstoppable machine gearing up for the sacrificial slaughter of World War I. In Portrait of a German Officer (1914), the beautiful soldier he was said to be in love with, is idolized as a sacrificial victim on the Iron Cross. The combination of horror and excitement as people gathered around the frenzied war machine must have been intense—all of this packed into an unspeakable parade of calmly accepted insanity, and Marsden was painting it as he felt it: intense, structured and yet incredibly expressive.

Marsden was sensitive—a reader of the occult, myths and a lover of symbols, hieroglyphics and forgotten cultures. His American Indian paintings, which are also part of the show but completely opposite in tone, are hierarchical depictions of a way of life that is content, close to nature, and centered around the female symbol of the open teepee door—they are beautiful even if you don’t like the American “savage.” I believe the Berlin paintings are about sacrifice—the sacrifice of young men by the thousands in order to unify and cleanse the nations of fear. (Our primitive fathers were satisfied with goats and a couple of virgins. If this is progress, obviously we have lost our minds.)

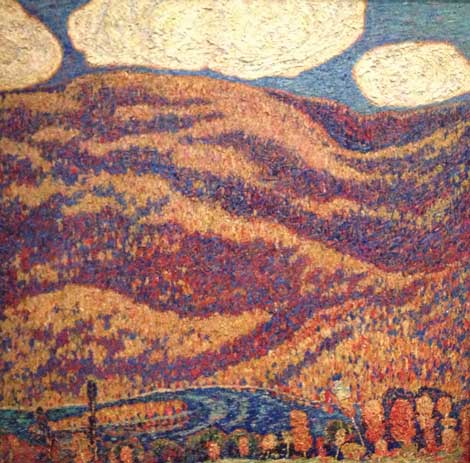

Perhaps I give Hartley too much credit, or maybe I am reading into his work more than I should? I don’t think so, because I didn’t think about all this until I saw his paintings. Interestingly, when Germany lost the war, shame settled on everything like a suffocating blanket and no one wanted to touch his paintings. No one wanted to be reminded and Marsden returned home penniless. I do not think he painted to impress people or to immortalize war. (How do you immortalize war—the happy rape of the Sabine women?) Marsden painted the vibes he felt at the time, unmoved by fashion or art theories—which brings us back to Dogtown. An artist’s raw ability to put so much wordless feeling into dirt, fences, and rocks is a topic I am virtually incapable of articulating. I can manage to squeak out the esoteric word primordial, but the next word would be more plain: magic.