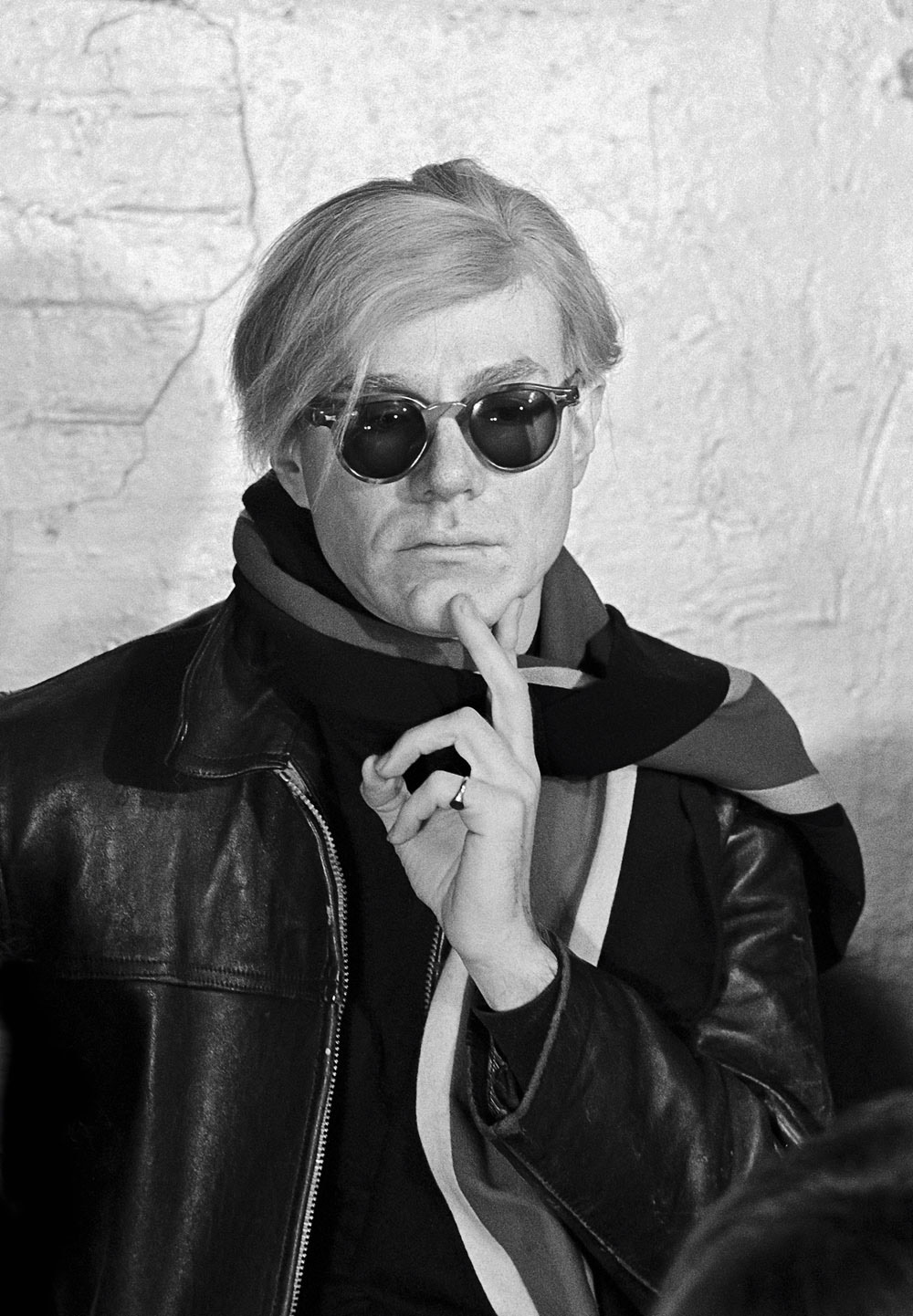

Andy Warhol was not a weak, whiney, limp-wristed gay man. Quite the opposite, in fact: he had different personalities for different people. To his nieces and nephews, he was your normal uncle Andy; they loved him and wrote a storybook about how they would wake up their wigless Uncle Andy—surprise, surprise. It described how he gave them all tasks to perform because work was the most important thing. So why did he put on this bizarre, non-human, often silent front for the public?

He was known for being cheap, but that couldn’t be true: He had a warehouse full of stuff he impulsively bought for himself. It was whispered that he was gay, which was not accepted at that time. Well, he wasn’t just gay, he was over-the-top gay, dragging around three of the most fabulously obnoxious drag queens—Candy Darling, Jackie Curtis and Holly Woodlawn—to every public event he attended, where they embarrassed everyone.

At first glance, Warhol seemed weak and non-confrontational (actually timid) due to his secret gayness. All of the other macho artists who were gay in private (Rauschenberg, Johns) maintained their straight facades. Andy was the only one who never pretended to be straight in public. His favorite pose when being photographed was to rest his fuck-you finger against his cheek. He infuriated people because he made them feel confused; they didn’t get it. His work was increasing in monetary value every day and they couldn’t see why.

Of course much of this was projection on my part. I didn’t know him well although I worked with him very closely for a number of years. Other people, like the Velvets, Gerard Malanga and Ondine were friendly with him, but I was too awed by him to make an intelligent assessment of my place in the Factory. Instead, I imagined I was Lancelot, and with enough speed I thought he was King Arthur and the Factory was the Round Table. Obviously out of my mind, I did not understand that I was witnessing a very original incarnation of the art scene.

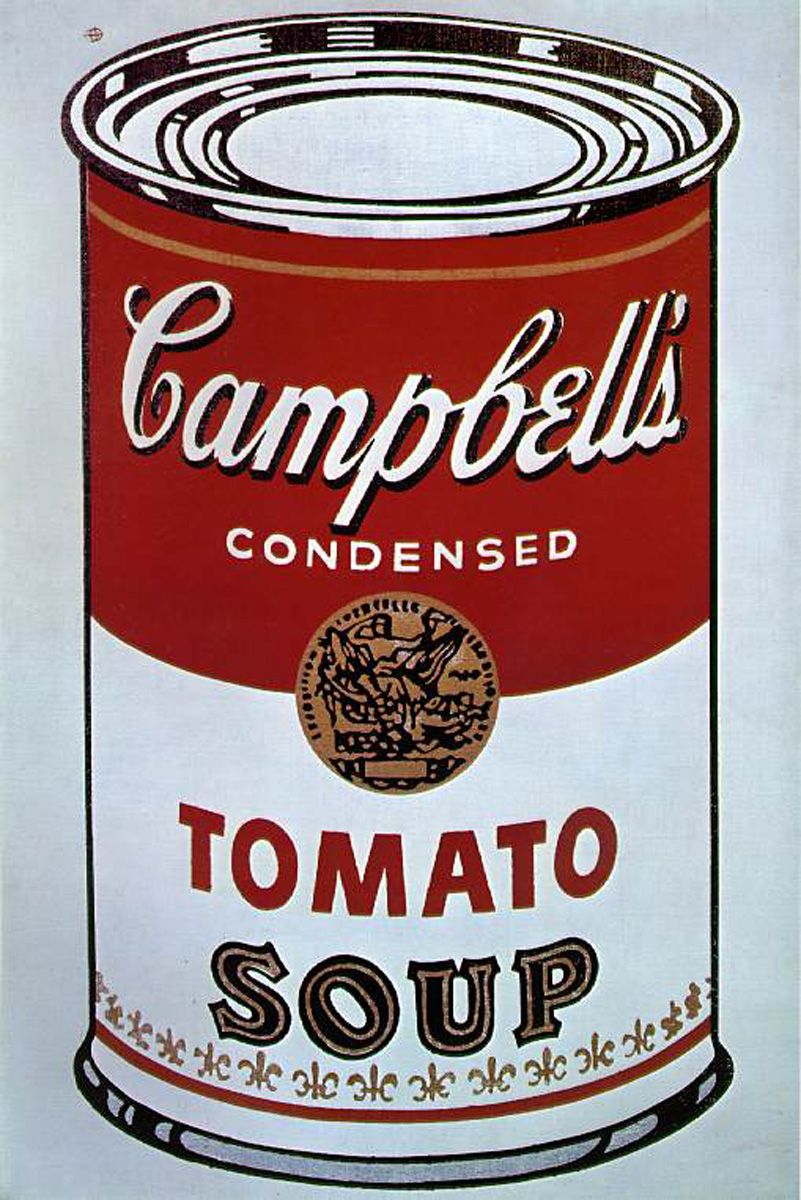

Warhol’s art was the first to be about the look of things. For instance, the Marilyn Monroes were about her makeup, not her face. The Campbell Soup cans were about childhood; an introduction to eating canned food as opposed to meals that were made from actual meat and vegetables. The Brillo Box was about your mom being on her hands and knees cleaning the kitchen floor and being happy about it. His movies repulsed people but they were about accepting people the way they were without camera angles and cutting, etc.,—without any Hollywood fucking shit. No artist had ever used the image to state these things so bluntly.

His art didn’t merely entertain, it questioned your assumptions. It was never there to pamper the eyes and make you feel comfortable, and it certainly didn’t sexually reassure you. I don’t know, does that count for something?