Diego Rivera’s murals are a tale—no, a single impression—of the epic journey of a country. It is chopped up into events, into battles, and years of endless marching and daily struggles. But the viewer still looks at a mural in a single moment and feels overpowered by the years of toil, the conquests of endless bloody battles, and the twisted pain of enslavement ending in the cadmium flower of yet another revolution, as the life of an entire nation stares back at you in one thunderous moment. Diego’s giant paintings are true murals that follow all the stories of a nation from one century to another. No small feat, but Rivera is a master weaver: His style does not vary; it becomes the voice of the people. There is no narrator with an interpretation, only the voices of everyone together.

The canvas is cut up into sections of the same quilt; the faces are all in the same style so they become the powerful single face of thousands. They are shown working and walking, men and women, all with the same hope, the same heart and the same intent—the sacrifice of thousands in the name of land, bread and freedom.

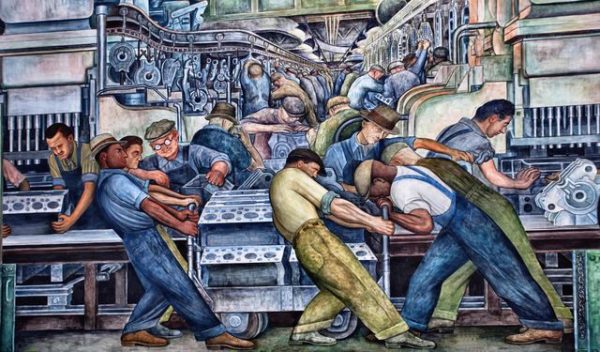

A portion of the north wall of Rivera’s murals in the DIA

There stands before you a noble race of people, the everyday suffering and the struggle against their oppressors, in battles to the death, sometimes victorious. Is this history or propaganda? Both, but it is also music: powerful, emotional and rhythmic. At first it looks like puzzle pieces scattered across the canvas. One worries about not being able to see everything at once, but there is not a piece of it that is forgettable. Every scene merges together into an overpowering human history that exists in a glance as opposed to an hour-and-a-half in a movie theater. Diego doesn’t paint a single flower—he paints a rhythm of flowers—not one but 30 Easter lilies, not one but 300 women marching. You can look at just a piece of the mural but the small face in the crowd of walking women becomes larger than life and suddenly you are part of that crowd. The motion of these women becomes epic, even immortal. A painting lifts you up into history, because you instantly understand it on a visual level, without a word being said.

Bluffton University mural

The painting of America’s new future is of millions of poor drug addicts waiting to die because there are no jobs. A million bottles of polluted water litter the ground instead of flowers. Our mothers will not be marching barefoot and victorious: They will be holding dead babies and staring at nothing, as they wait for their own death, which will be coming soon on black stinking wings. We are the only animal that thinks we can improve on Mother Nature instead of live with her.