Unlike Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s fascination with his models—whom he painted obsessively, much to the detriment of his painting—Robert Mapplethorpe’s photographs of Lisa Lyon show no signs of such frustration. Rossetti was like a man locked outside of a house to which painting was the key, while his muse stared vacantly out of the window. The more he idolized her, the more he deformed her, and the more she escaped him.

Mapplethorpe’s portraits of Lyon show a very different relationship between artist and model. First of all, I doubt if their relationship had anything to do with repressed or expressed sexuality. This usually results in compulsive repetition, like the hundreds of portraits by Picasso that look nothing like the model and are about an obsessive artist’s new style.

Mapplethorpe was different. He is the only artist I know of who allowed and probably insisted that his model get off her stool and have a voice in his art. Either she was very intuitive or he was very accepting, but probably they were just good friends capable of listening to one other.

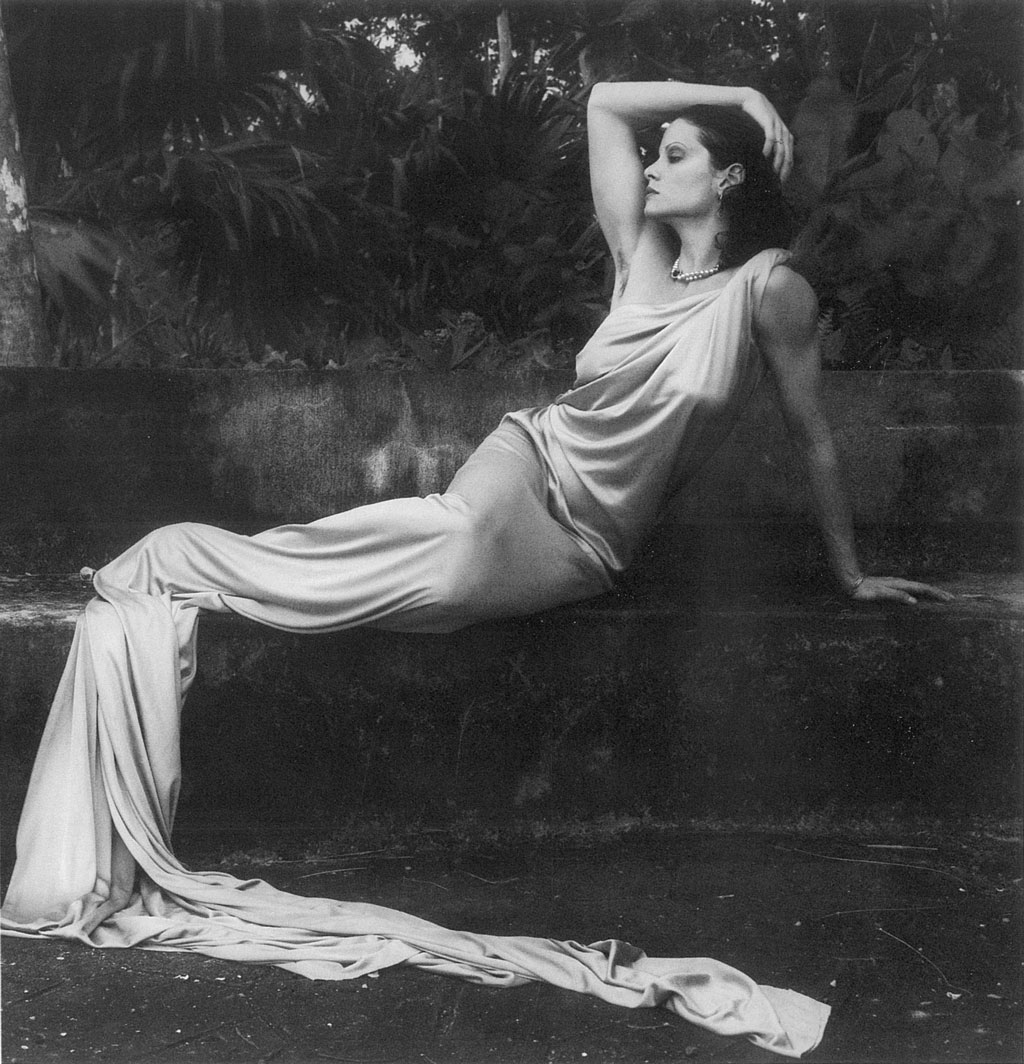

Robert Mapplethorpe, Lisa Lyon, 1982, Gelatin silver print, Promised Gift of The Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation to the J. Paul Getty Trust and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, © Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation.

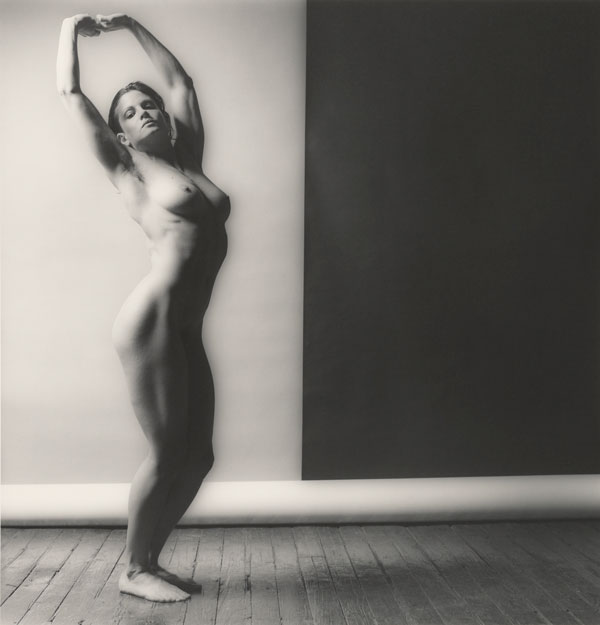

And Lisa didn’t consider herself just a model, or yet another body builder; she considered her body to be a living, breathing work of art. And she was the artist who constantly sculpted that body as a performance piece. If you look at the female bodybuilders in the magazine Pumping Iron, you can appreciate the difference.

Lady: Lisa Lyon is the book of photographs they created together, and gender slippage is the idea they shared. I first heard this term in the ’60s, used by the Ridiculous Theatre Company, where drag queens did not try to be real women. Instead, they were sarcastic yet funny, and often made outlandish comments on femininity. As with the late and great Holly Woodlawn, “drag” was their choice of wardrobe, and “queen” was their choice of attitude and style. They mocked women, but at the same time bore their own humiliation bravely. Lisa perfected another phase of this art form by literally joining female and male in the same body: grace curled around strength.

One could say her job was harder than Mapplethorpe’s. All he did was click the camera, while she sweated away hours of muscle-building torture in some dark gym. But I disagree. His art was to understand her performance, and his genius was to enhance its message. Perhaps they argued over which props to use, but he supplied the light and the terrifying stillness, and the somber weight of black and white. They were both artists working together to create something: A feeling? An exciting impossibility? A poetic expression that did not exist before the combination of his light and her body. He was the magician of shadow and light, and she the performer in a balancing act—between gay and straight, vamp and virgin, male and female.

Photographs by Robert Mapplethorpe on view simultaneously at LACMA and The Getty through July 31, 2016.