China had its first major avant-garde exhibition in 1989, which was also the year of the Tiananmen protests. The exhibition “Art and China after 1989: Theater of the World” (through Jan. 7, 2018) at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, acknowledges that sea change, and ambitiously tries to track the major sociopolitical changes in post-Mao China with its contemporary art. “No nation in modern history underwent such a total transformation as did China during these two decades,” lead curator Alexandra Munroe writes in the accompanying catalogue. “The artists in this exhibition see themselves as both agents and skeptics of this accelerated change.”

The largest exhibition of contemporary Chinese art ever in North America, numbering over 150 works, “Art and Change” has also been highly controversial—before the opening, three works were dropped by the museum after well-publicized protests by animal rights activists. However, it seems to me that controversy is just what many of these artists courted when they made these works, as they struggled against the accepted norms and received wisdoms of an authoritarian system.

Take the two works by early conceptual artist Huang Yong Ping that one encounters when heading up the museum’s spiral ramp. The first, a modest pile of dried pulp placed atop a piece of glass balanced on a wooden box, is The History of Chinese Painting and A Concise History of Modern Painting Washed in a Washing Machine for Two Minutes (1987/1993). Huang put two stuffy art history texts, one in Chinese and one in English, in the laundry and disengrated them—perhaps the wish of many a disgruntled artist, and certainly in keeping with Huang’s own Dadaist inclinations.

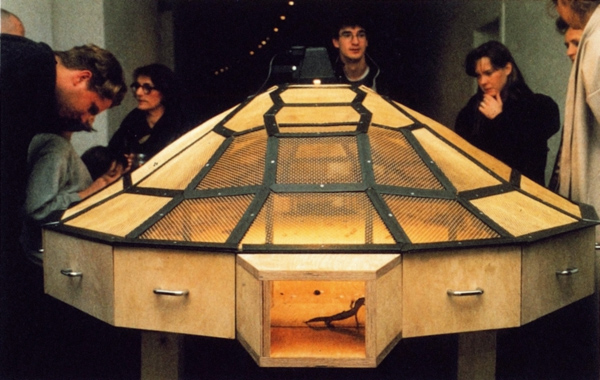

Huang Yong Ping, Theater of the World, 1993, Guggenheim Abu Dhabi, © Huang Yong Ping.

Nearby is the apparatus for his installation Theater of the World (1993) which gives the Guggenheim exhibition its title. It’s a faceted box covered with a mesh top through which one might see insects and reptiles play out Darwin’s survival of the fittest. Except now it’s empty because it was one of the “offensive” works. (The two other deleted works were videos, now represented by a monitor with an artist’s statement.)

The exhibition includes classics of the contemporary Chinese art canon, such as Wang Guangyi’s Mao Zedong: Red Grid #2 (1988)—a portrait of Mao in black and white, mysteriously and perhaps subversively behind a red grid. The artist was questioned about this work by authorities when it was submitted for the China/Avant-Garde show of 1989, and he cleverly responded that it was a way of looking at Mao “rationally.”

Ai Weiwei

The two best-known Chinese artists, Ai Weiwei and Cai Guo-Qiang, are given their due. There’s Ai Weiwei’s famous series of photographs from 1995 showing him dropping a Han period urn—and letting it break at his feet. So much for traditional culture! On another wall is the list he compiled after the disastrous Sichuan earthquake of 2008, a list of the children who died largely as a result of shoddy building construction. Cai is here with one of his large-scale gunpowder “paintings”—works done with exploding gunpowder, plus ink and brush—as well a video from the opening and closing ceremony of the Beijing Olympics of 2009. In the latter he designed the impressive fireworks displays—a field he has elevated to an art form.

Unfortunately, only a handful of women artists are represented here, including Lin Tianmiao and Ellen Pau (who is from Hong Kong). Munroe has said that this is due both to the chosen time period of the exhibition—it was an era of few women artists—and to its focus, which is on conceptual work. From what I’ve seen, however, even to this day few Chinese women artists have broken through the glass ceiling.