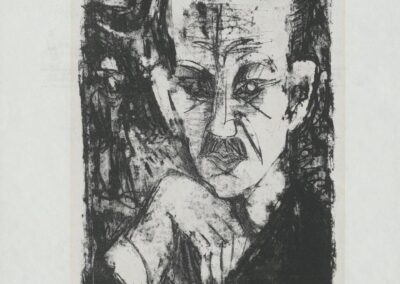

He had five of them—hats that is. Part cowboy, part fedora—they saw him through the presidency like stalwart protectors. They gave him confidence. They engendered a swagger. They saw him through the race riots, civil and civic unrest, and the anti-war protests that marked him, in our collective American consciousness, as a failure. Far from simple head warmers, those hats exemplified a huge and robust personality. However, there was, in fact, a lightning bolt with his name on it, waiting there in the sky, and nothing could stop it—not the expanded New Deal, not Medicare, nor the Clean Air Act, not the Civil Rights Act of 1964, not Headstart—or his lucky 5 gray hats. Nothing could save LBJ from himself.

He had sixty of them—cigarettes that is—every day for most of his adult life. The hats, ever protective, hated the cigarettes, and the cigarettes, of course, despised the hats. A pernicious battle ensued where the hats tried their best to block access to the cigarettes, even going so far as to fan the smoke from LBJ’s face, but there were simply too many of the damn things to make any difference. Conversely, the cigarettes knew their place in the hierarchy of importance as they related to LBJ’s life and well-being, and relished in the fact he would not stop smoking, except of course for the fifteen years between 1955 and 1970 after suffering a near-fatal heart attack.

Still, the allure was too much for him, and once again the cigarettes beat the hats in an all too familiar standoff. Where once the lucky gray hats held precedence in LBJ’s illustrious life, Camel Lights became the go-to mainstay right up until that fateful day in 1973 when the cigarettes had the final word and all his favorite gray cowboy hat could do was fall to the ground, slumped, and defeated like the great man himself.