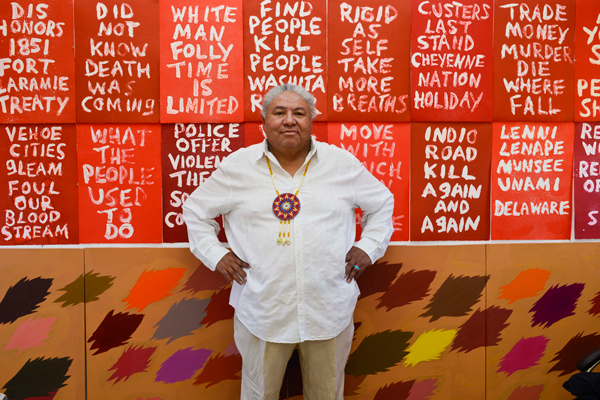

Cheyenne artist Edgar Heap of Birds has made a practice of illuminating Native-American life against dominant culture erasure. In his recent LA-area exhibitions at Garis & Hahn and the Pitzer College Galleries, he focused on activism and history.

You tell stories of, and advocate for, indigenous peoples. How does increased urbanization affect this?

For indigenous tribal citizens, I advocate participation through referencing the homeland and preservation of the community. That pertains to urban populations, too; I look back to the native origins of citizens, not only to preserving their culture, but by participating in it. It’s not a concept but an activation of their location. Where I am (Oklahoma,) we have many traditional ceremonies and people engaged in those. Urban centers are more dispersed and assimilated, but I still advocate participating in a community. This isn’t just a place I go to for subject matter—it shouldn’t be. No matter where you are, connect with your community and help out.

How does language preservation and dispersion figure in your work?

My “Native Host” series (civic signage that reveals the location’s original native name) has been going on since 1988, all over the U.S. and Canada. The native language, the tribal names, are more of an insistence on representation and, in a sense, agency. It is an intervention, a reclamation, saying “this is our territory, this is our history.” Without the language, everything is overlooked—America eclipses it with its own history. Reclaiming land through the language and traditions is so important. There is total amnesia about that history.

How does “Defend Sacred Mountains” at Pitzer College address land?

I focus very strongly on origin. Land is origin. It is also sovereignty. This show (about sacred native land under threat from commercial interests) is about origin, sovereignty, and also ceremony. Ceremony is how you address land. It’s almost like a religious connection, a stewardship and collaboration with land. When I address the land in my work, it’s about being humble. We are so incidental to this planet. People are important to each other but not to the planet. They pretend to have status but it’s self-made. So, mostly, the tribes seem very humble to be on this planet. They start there and stop there. That is what I’ve learned in over 30 years of my ceremonial training in the Cheyenne tribe.

Do you mentor native artists?

Yes, but I also mentor many races of people. I have to engage everybody. I think that’s important. I have former students in LA: Chris Christion (African American); Kade Twist (Cherokee) at Otis, who was in the 2017 Whitney Biennial and was one of my students in Native American Studies. Also, Michael Maxwell, a New York artist with a native perspective on land and responsibility. It’s great to see non-native artists pick up on some of the native precepts that are positive. That sort of transition is productive.

And navigating activism and commerce?

Don’t be mesmerized by the market. Some artists are. I try to stay focused on important goals, culturally and artistically. I’m not involved in the market—in the studio or in the interventions I make. The market comes afterward. I like my work to be seen, travel for a few years before it gets locked up, out of sight. It has to address people and get an exchange of ideas. If the market can aid in this, great, but I’m thinking about the mission of the culture and art, before the market.