Until his suicide in 1995, Ray Johnson was one of those fringe artists that most artists had heard about, but very few were familiar with. Even then, it wasn’t until John Walter’s 2002 biopic How to Draw a Bunny—certainly one of the best biographical art documentaries ever made—that Johnson began to gain some household-name traction. Weirdly, though, there are only a handful of monographic books devoted to Johnson and his art—most of which predate the movie, and usually fetch over $100 used on Amazon.

LA-based Siglio Press has gone a long way in correcting this deficit with a simultaneous double shot of superlative archival publications—a new anthology titled Not Nothing: Selected Writings by Ray Johnson, 1954–1994, and The Paper Snake, a facsimile reprint of a 1965 artist’s book assembled by Fluxus artist Dick Higgins from his collection of Johnson ephemera, and originally published by his own Something Else Press.

While a sumptuous and quintessential early representation of Johnson’s oeuvre, The Paper Snake isn’t radically unique, as any book or exhibition detailing the Mail Art pioneer’s career would pretty much have to consist of a “collection of Johnson ephemera.” After lucking into attending Black Mountain College during the period when John Cage, Merce Cunningham, Willem de Kooning and Buckminster Fuller were guest faculty (not to mention the hard core of stellar Bauhaus refugees that ran the place), Johnson moved to New York—rapidly outgrowing his accomplished abstract geometric painting style to develop an idiosyncratic and quietly revolutionary collage practice that is rightly ranked alongside the work of his Neo-Dada colleagues Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg.

This is around where Not Nothing picks up, beginning with his seminal faux-manifesto What is a Moticos?—a question which he doesn’t answer very helpfully, and which still puzzles scholars today. “The next time a railroad train is seen going its way along the track, look quickly at the sides of the box cars because a moticos may be there…” he informs us, “Perhaps you are the moticos.”

As best as I can make out, a moticos is a sort of semiotic event—a unit or cluster of meaningful phenomena, taking the form of one of Johnson’s extraordinary, irregularly shaped collage works, which he exhibited in larger clusters on the streets of New York City in the late ’50s and early ’60s—or manifesting as one of the seemingly endless stream of punning concrete poetic dispatches that issued from his pen and typewriter.

Reasonably enough for an imprint that focuses on works “that live at the intersection of art and literature,” Siglio’s double dose emphasizes the latter manifestation, though by the mid-’60s—with the advent of Johnson’s mail art practice—his virtuosic collages and linguistic pyrotechnics became inextricably intertwined in a prototypical relational exercise that undermined the prerogatives of marketplace and authorship while articulating a rhizomatic network of creative alliances that persists to this day.

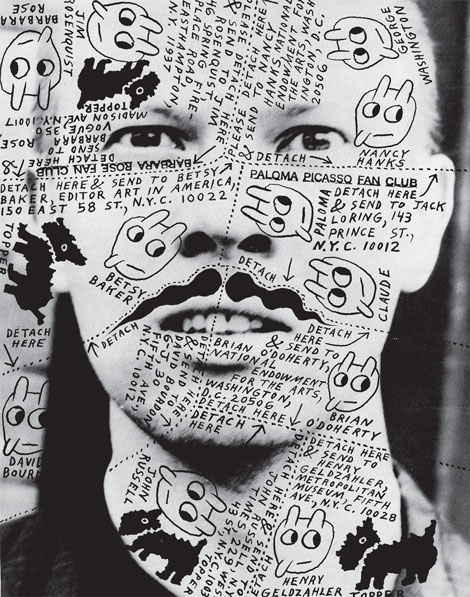

Plate 101 from Not Nothing: Selected Writings by Ray Johnson, 1954–1994. © Estate of Ray Johnson, courtesy Richard L. Feigen & Co.

Nevertheless, Johnson’s oeuvre was so enormous and tangled that some sort of filter is needed in order to gain a foothold, and his literary side is an inspired choice, as the humor and formal beauty of his drawings and collages (not to mention the grand conceptual sweep of his visionary postal intervention) have usually overshadowed his considerable gift as a wordsmith.

Perhaps the most winning facet of Johnson’s writing was his anecdotal storytelling, which often hinged on the observation of quirky quotidian details, usually conjoined synchronistically to the addressee’s recent visit or communication with Johnson: “Bill, Thanks for the lovely Swan’s nests postcard with information about deadeye deadeye deadeyes. I saw fourteen swans yesterday at the beach,” or, on letterhead from the NYC Department of Housing and Buildings and headlined VERY IMPORTANT: “Carol Berge, After saying goodbye to you on the crosstown bus—I found thrown away a tall black bar chair with three legs—one leg missing. I carried it home. I washed my hands in warm water. They were so cold. Red Eyes.”

The fact that these gnomic utterances are directed to such noteworthies as Josef Albers, Andy Warhol, Linda Benglis, Lucy Lippard, Willem de Kooning, Christo, etc.—all friends of Johnson’s—lends an added cultural historical resonance, and it’s hard to imagine a more comprehensive and satisfying sampling than Not Nothing. But it is the slimmer reprint of the Paper Snake volume that alerts us to how extraordinary—and how extraordinarily beautiful—Johnson’s practice was in context. Imagining coming across such an exquisitely peculiar artifact in the era of The Great Society reminds us of a time when the avant-garde wasn’t just a marketing niche and when an artist could work honestly, tirelessly and courageously on remaking the world according to his own vision, one moticos at a time.

Not Nothing: Selected Writings by Ray Johnson, 1954–1994

sigliopress.com/book/nothing