As the philosopher Lindsey Buckingham once observed “You win prizes if you stay, because that’s how we do it in LA.” When I landed in here in the very early ’90s, there were a number of local art legends who had been working the program for decades, yet seemed to have been misplaced in a fog of historical amnesia.

Probably the two most prominent of these were Llyn Foulkes and George Herms, both of whom are now approaching their 80-year mark, and as a result have been catching up on the love they never received as mid-career uncategorizables.

Foulkes’ delayed appreciation isn’t so surprising—cranky-ass bite-the-feeding-hand kind of a guy that he is—but what are we to make of Love God Herms’ long dark night of institutional and media blackout? After all, the man has been radiating benign beatitude since he first staked a claim to West Coast beatnik glory with his first solo show in 1957. A founding member of the West Coast Assemblage movement alongside Ed Kienholz, Wallace Berman and Bruce Conner, Herms generated an enormous body of work relatively untouched by the hermeticism and sociopolitical angst of his associates.

Maybe that was the problem—Herms’ lack of gravitas made for an easy transition from beatnik to hippy, and the positive sincerity of the hippy agenda was never an easy sell in the art world. And staying alive so long is definitely not a good career move. At least not in the short run. But like I said, lately things have changed. In 2011, Herms had no less than six solo shows, and although not yet the subject of a major museum retrospective at any of LA’s larger institutions (Heavens!), longtime sport Ed Ruscha and ex-Tamarind master printer Ed Hamilton have conspired to preemptively issue the catalog.

The River Book takes its title from the first line of the brief, nostalgia-tinged essay by Dave Hickey that opens the first of two slip-cased hardcover volumes: “George Herms is a river unto his people.” Which I’m guessing is a mutant reference to Bedouin chief Anthony Quinn in Lawrence of Arabia. I can dig that. Except instead of Turkish gold, Herms’ tribe have been able to rely on him—over close to six decades—for a steady stream of scrap metal, rusted signage, discarded office furniture, sad dolly parts and used coffee filters.

Apart from Hickey’s essay, the back material, and a handful of deep captions, The River Book consists of a chronological excavation of the Herms oeuvre, encompassing beachcomber altarpieces, magazine collages, ritual-ready environments, concrete poetry letterpress publications and at least one Free Jazz opera (performed at REDCAT in 2011 and documented on an included DVD). Plus a previously unseen portfolio of period photographs depicting the Berman clan, Ray Johnson, Diane di Prima and other playas.

This progression of imagery—curiously verbiage-free, given Herms’ affinity for poetics—is sumptuously printed, with a respectful, unobtrusive design that emphasizes the formal design strength lurking beneath the filigreed surface decay and the stain of memories lost and recovered. Ultimately, Herms reveals himself to be more a member of the Kurt Schwitters/Joseph Cornell axis than one of the more content-driven angry young polemicists of Generation W.

Apart from the always-reliable anti-West Coast bias that keeps balance in check (not to mention the truly revolutionary alchemical implications of turning yesterday’s discarded consumer goods into cultural crown jewels), Herms’ work epitomizes the vocabulary of found material assemblage that had an enormous—and universally scorned—impact on amateur (French for “lover”) art-making around the world. But that’s a whole other rusty can of worms.

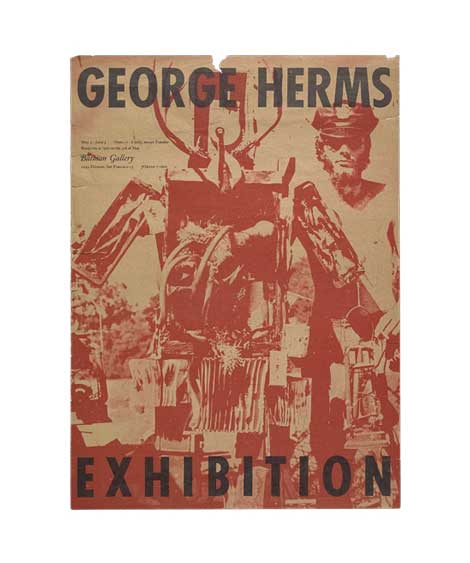

Probably my favorite detail of this splendid publication is an easily-missed structural conceit (assuming it was intentional—with this crowd you never can tell when it’s the Peyote talking) that emphasizes the triumph of longevity. The first piece documented in the book is the lost effigy of Hugo the Aquarian (1961), the totem figure of Herms’ solo show at the Batman Gallery in San Francisco. Black-and-white photos first show the piece, then its abject destruction, in a failed attempt to levitate it over the Corta Madera Creek for a film by fellow traveler Paul Beattie.

All the way at the far end of the 400 pages and 50 years of junkyard epiphanies, on the DVD at the climax of Herms’ Free Jazz opera The Artist Life, Herms straps himself in a harness and soars joyously over the musicians, the rusty props and the audience, air-drumming furiously in front of a big-screen blowup of an echocardiogram video of a beating heart. Free of all the detritus that has flown from his river, Hugo Ascendant is frozen in a gesture of benediction. Cut to inter-title card: To Be Continued. It’s the kind of prize worth sticking around for.

George Herms: The River Book

Texts by Dave Hickey and the artist,

Hamilton Press, Venice, 2014.

Two hardcover volumes in a printed slipcase, 408 pp, 154 b/w, 244 color, DVD, $95.00

ISBN-10: 0615953913