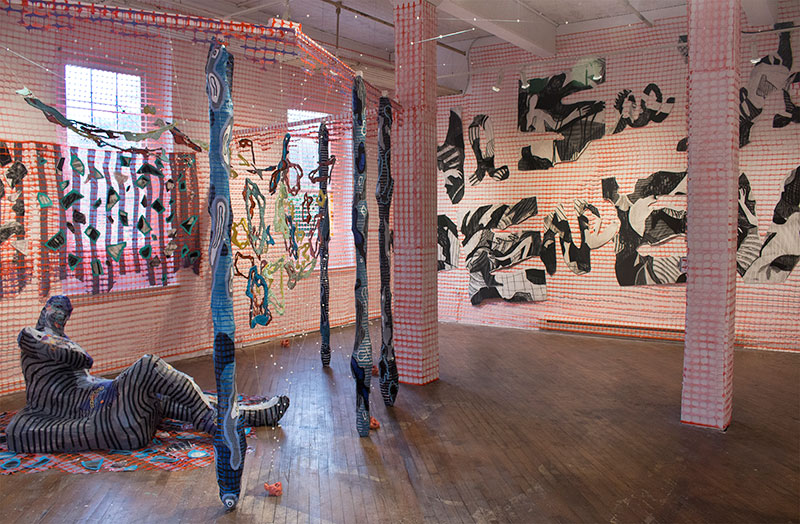

The arresting neon orange construction fencing fixed to the walls of Automat Collective’s gallery space vividly sets the tone for the tales of romantic drama contained within artist Rachel Deane’s installation Mending. The black-and-white bubble letters layered on top give the impression of a hastily-scribbled “Dear John” letter or a hodgepodge-y ransom note. Standing back from that large text, we read “we see your perseverance and will stand as its monument.” Mending is a monument to survival in the face of doomed love and misplaced lust, of miscommunications and hurts literally sewn into being, all based on 25 of the artist’s own relationships.

If the agitation and ramshackle atmosphere created by that warning-bright orange material weren’t enough, reading the rather extensive explanatory text reveals that the words are cut from Deane’s drawings of famous compositions that portray violence against women—The Rape of the Sabine Women, Susanna and the Elders, Apollo and Daphne—placing Deane’s own tragic relationships in this artistic and historical-mythical lineage of women being hurt by men who refuse to take no for an answer. Thus the “perseverance” in the text is at odds with the underlying visual references depicted inside said text, meaning that the phrase comes across more as a taunt than encouragement. Deane—and women—will be hurt, the display seems to say, and the men responsible will still be left standing when it all blows up.

The centerpiece of Mending is set apart from the rest of the installation, located in a quasi-alcove cut off from the charcoal drawings by encircling posts and strands of material around and above it, almost hermetically sealing it from the aggressive tug-of-war outside. In the center is Deane’s “three-dimensional figurative painting” that, in practice, is a sculpture of a humanoid figure sitting on a futon cushion.

Leaving behind aggression means entering into more subtle forms of romantic devastation, and it takes genuine work to figure out to how get past the physical boundaries and obfuscation and access the sculpture. The figure leans back easily, resting on one arm, inviting you to sit next to it on the remaining slice of cushion, yet both human-figure and cushion are covered in the same piece of dark fabric, literally connecting them. Sewn into the surface of this fabric are snippets and recollections of bad relationships: “he pulled my hair and slid his tongue down my throat”; “he fucked me on Halloween because he felt sorry for me”; and, tellingly, “I’m not emotionally interested, but you have great tits” stitched right by the crotch.

If Mending is about the subtle (and obvious) ways people in relationships hurt and can be hurt, then this sculpture, and its isolated location in the gallery, is like that proverbial guy who doesn’t want to be seen out in public with you, but is happy to date you behind closed doors. He’s set apart from it all like that wound that will not heal, the specter of the worst broken heart.