Lebanon-born, Los Angeles-based painter and sculptor Rabbia Sukkarieh regards her art as a means of transmuting a traumatic past. Having experienced the 1975–90 Lebanese Civil War, she creates ambiguous abstractions combining tokens of comfort with elements relating to her memories of internecine strife. Sukkarieh’s paintings, drawings and sculptures in “DARKEVENTWHITEHORIZON,” at Robert and Frances Fullerton Museum of Art, are rooted in personal associations yet remain agape to viewers’ interpretation.

Her largest paintings, Sabra 1 (2016) and Sabra 2 (2017), feature weblike networks of black, white, red, orange, green and yellow splotches that coalesce, at a considerable distance, into expansive compositions. As one approaches either painting, its inscrutable pictorial structure disintegrates into mosaics of irregularly mottled patterns whose constituent shapes vaguely resemble those of camouflage print. These enigmatic abstractions were partly derived from scenes of the notorious 1982 Sabra and Shatila massacres in West Beirut, which had occurred near Sukkarieh’s home. With her representational sources layered and transformed to the point of unrecognizability, the finished paintings betray little indication of their horror-laced origins. Thus, the artist has symbolically abstracted the bloodbath into oblivion; and with it, perhaps, her pain of its memory.

While Sukkarieh refers to her two-dimensional works as expressionistic, her premeditated methods diverge from the dashing brushwork generally associated with Expressionism. Her strokes are smooth and studied; her compositions are carefully planned. One can sense the artist searching for catharsis through contemplative repetition. This interpretation is substantiated by Sukkarieh’s emphasis on having mixed her hues from only four paint tubes, including red and yellow, which she describes as Buddhist healing colors. Similarly, a slew of drawings portray unnameable dark forms agglomerated from meshes of copious inessential detail. In these, her assiduous movement of pencil over and across paper seems to stem from a Zen-like preoccupation with reiterative activity.

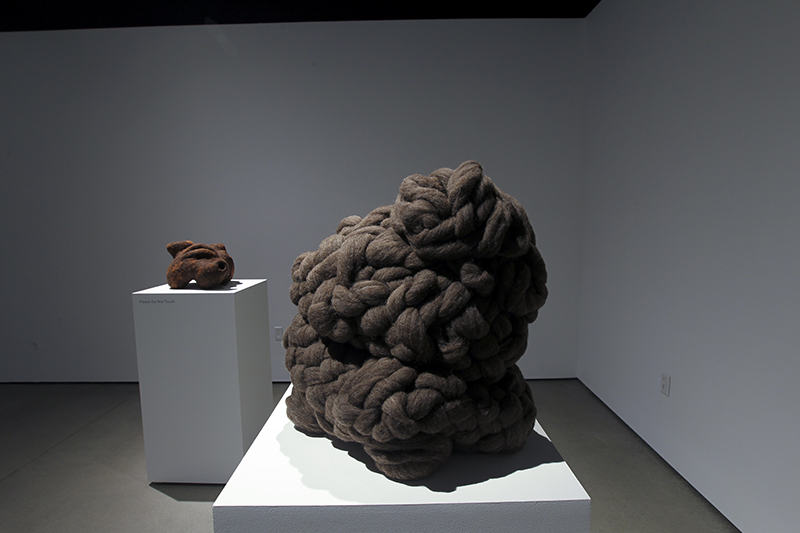

Most expressive are her woolen sculptures, whose morphologies often echo the shapes in her drawings. Many appear vaguely corporal. Untitled (2017) is a clot of rusty reddish-brown wool bearing gaping holes suggesting wounds or bodily orifices. The puffy, bulbous arch comprising White Hole (2018) is amassed of black wool whose fluffy surface texture brings to mind cotton candy spun of charcoal. Sukkarieh’s titular reference to a white hole—a spacetime theory bearing negligible relation to the subject at hand—distracts from this sculpture’s real-life presence, which evokes billowing towers of smoke or the gloomy entrance to a lava cavern.

Wool traditionally bears comforting associations of softness and warmth, but here it appears somber and eerie. Sukkarieh’s use of wool relates to childhood recollections of her grandmother weaving rugs and her mother knitting sweaters with the family gathered around a stove during winters in her hometown of Baalbek. Yet she also says it now reminds her of the hair of innocent souls having lost their lives in bloody frays. Such dichotomous symbolism affirms that even one’s fondest memories can be tainted by the horrors of war. Sukkarieh’s work seems driven by her conviction that art can help untangle emotions jumbled by trauma.