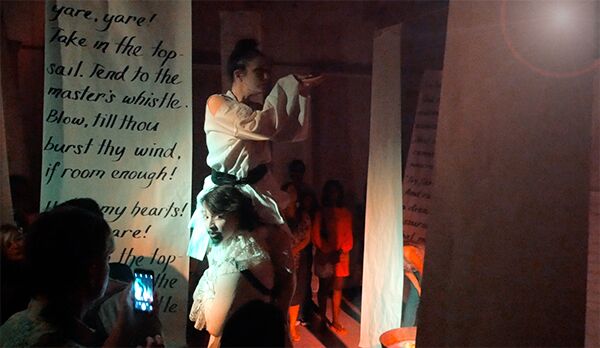

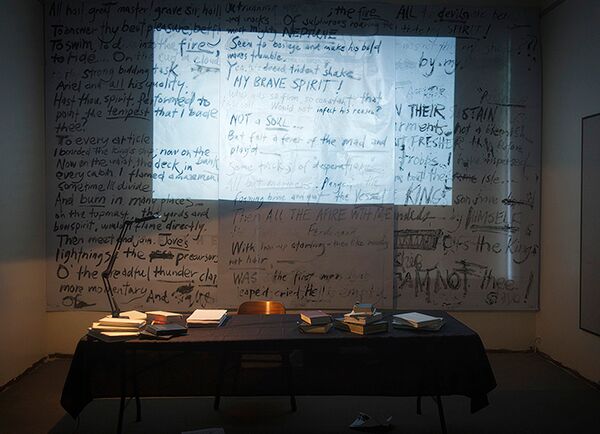

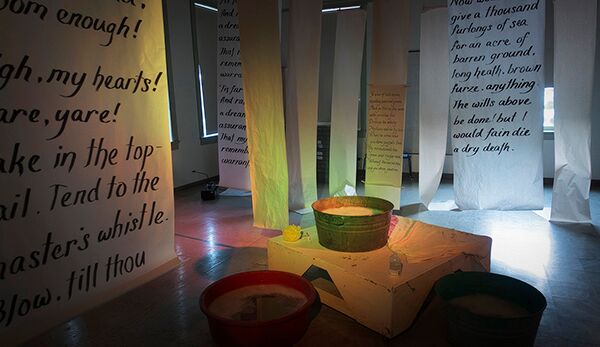

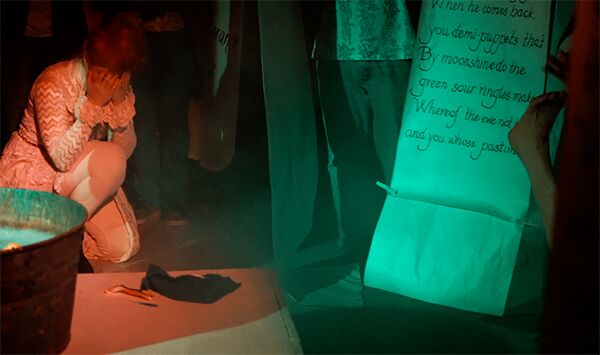

Artist Masami Teraoka said, “Let’s make art!” and they did. Pure art rumbles, bubbles and springs forth, like the eruption of a magnificent geyser. As the plume spray drifts and evaporates in the wind, the beauty of the gesture is the impermanent purpose. A site-specific, immersive interpretation of Shakespeare’s The Tempest was conceived, planned, strategized and rehearsed for a singular performance. Russian director Viktoria Naraxsa, a Pussy Riot partisan, Masha Kechaeva, the stage and costume designer and a local pick-up crew of actors, craftsmen and producers have presented a beautiful and transformative dream. With one performance, the event lingers as a memory lost to the trade winds.

In the arts, collaboration is a beautiful risk. Artists are often imprisoned in their studios, minds and habits. Collaboration oxygenates the art-making process. Creation is the goal and destruction is the chance.

Most often, artists are isolated islands. Masami Teraoka is an artist who lives on an island.

OF A LIKE MIND

Painter Masami Teraoka loves Pussy Riot, the brave Russian arts collective. Out of his great respect, he wanted to work with them. His adoration grew with a logical progression. In the early part of this century, after a long study in Europe of Medieval and early Renaissance art, the Oahu-based artist became fascinated with religious history, influence, power and ritual, as well as its inherent oppression, deviancy and hypocrisy. With The Cloisters Last Supper Triptych Series, the painter devised capital pieces of muted color and gold leaf. In the figurative work, religious fervor bled into sexual ecstasy, brutality and madness.

At this time, in February of 2012, a Russian arts collective, Pussy Riot, overtook the sacred Cathedral of Christ the Savior in Moscow. Their impromptu punk rock concert on the altar of the Orthodox Church was an international scandal, an angry protest to the heavy boot heel of President Vladimir Putin. In short order, the three female leaders of Pussy Riot, all quite beautiful, were arrested and harshly imprisoned. Said Teraoka, “Pussy Riot’s concert had symbolized a perfect theme. Suppressed individual freedom versus oppressive government control.” The band’s visages began to appear in Teraoka’s paintings. “My major large triptych series eventually moved into a Pussy Riot Series.”

THE FEVER

An islander, Teraoka wanted to work with Pussy Riot. “I was inspired by their vision and philosophy. Basically, they are asserting human rights and individual liberties. When I watched their concerts, I was convinced they are a powerful group.”

After appeals in court and years in prison, the remaining two Pussy Riot jailbirds emerged from the gulag as international celebrities.

Teraoka’s passion was well known to his gallerist in San Francisco. The artist recalls, “The initial contact had sprouted from the Catharine Clark Gallery. (Catharine) went to see the Pussy Riot performance (at the Warfield in San Francisco) and she managed to give my book Ascending Chaos to their team manager.”

MESSAGE IN A BOTTLE

Eventually, the painter tried to make contact with leader Nadezhda “Nadya” Tolokonnikova, but that is not a simple thing to do. It is easier to book Katy Perry or Rihanna for a first birthday. (In the Hawaiian culture, a first birthday party is as sacred as a Beverly Hills bar mitzvah. In the post-colonial contact past, most Hawaiian babies never made it to their first birthday, now a true cause for celebration.) Ever earnest, Teraoka finally made contact with Nadya through Facebook. At the time, she was in New York with her friend and colleague Viktoria Naraxsa.

Fear is very much a factor in the Moscow arts community. After release from prison, Nadya found herself to be a pariah, a political liability. She was having trouble recruiting talent for her projects. No one wanted to play in her mine-filled sandbox.

Now in her late 20s, Viktoria Naraxsa grew up in Khabarovsk, a harsh city in eastern Russia. She recalls, through her translator, “Even at age five, I understood what a hellish, sad place it was.” The support of loving parents was a buffer to the town’s “aggressive, war-like mentality. There was no medium. You were a bully or were bullied. Any odd one was out. I had one friend.”

Meeting through a mutual colleague, Nadya and Viktoria became fast friends. Choreographer Viktoria Naraxsa was directing the debut of a stage musical, loosely translated as Cockroach, by Korney Chukovsky, the Russian Dr. Seuss. Viktoria gave Nadya a small role as a piano player. This casting choice may have been a factor in the banning of the play. It was alleged that the text defamed the glory of President Vladimir Putin.

The two strong women shared ideas and values. They began to collaborate. Viktoria directed and choreographed the stunning Pussy Riot video, Chaika.

In New York City, Nadya began to receive messages from a famed Japanese-American painter based in Hawaii. The artist was proposing some sort of collaboration based upon their common values of freedom and expression. Nadya shared the many missives with her friend Viktoria. Naturally, language almost sank the new ship. Teraoka and his associates bombarded the Russians with a series of messages that were lost in translation. Misinterpreted ideas, business budgets and schedules overwhelmed the now maddening project. Says Viktoria, “Then Masami sent a letter from the heart. He spoke of his childhood in Japan and his values. It [became] a merger of interests.”

CREATION

English is a second language for Teraoka; Viktoria speaks not a word of it. Back in Moscow, planning for the unrealized Hawaii theatrical production became a comedy of errors. “Writing was difficult. Understanding was almost impossible,” said Viktoria, “All of Moscow was helping us translate. Each translation was different than another, but we wanted to make it happen.” Modern technology, like a promised Tower of Babel, was of little help. “I would write, ‘We need five actors,” said Viktoria, “Google Translation would tell Masami ‘We need five strippers.”

On Oahu, the painter dropped his brushes. Collaboration was exciting. His new role as producer and impresario kept him busy. Budgets were estimated, locations were scouted, talent was searched and approvals were sought for a production that had an unrealized concept. Communication between Moscow and the artist’s studio in Waimanalo was vociferous and daily. Miraculously, a mystery backer emerged with a promise to financially underwrite the project. My sources tell me that the artist’s collectors became nervous with the Russian intrusion. They wanted Teraoka facing, not the stage footlights, but a canvas with a wet brush in his hand. The show was on!

Freedom and expression was the thesis. Always an interest, Viktoria wanted to bring Russian author Yevgenia Ginzburg’s 1967 opus to the stage. Her celebrated Journey into the Whirlwind documents the horror of her decades-long persecution and imprisonment. The cold white of Siberia is unconscionable and inconceivable in sunny bright Hawaii. At Teraoka’s urging, two months before the curtain would rise, Viktoria turned her attention to another project on her wish list, magician Prospero’s island in Shakespeare’s The Tempest. The parallels were too lush to ignore for the director. The history of Hawaii is a tragicomedy of colonization. Like the play, Hawaiian legend is rife with ethereal gods and human royalty. “Like Pele and Queen Liliuokalani,” affirmed Viktoria, “Shakespeare’s Miranda is an island girl. I liked it because the pivotal scene is a wedding, a merger of nature and civilization, a marriage of the passive and aggressive, magic and reality.” Later, the director confessed to me that she does not believe in a God, but she does believe in magic. Like Prospero.

REALITY AND DREAMS

Plane tickets were purchased and arrangements made. Fortunately, Viktoria Naraxsa and the set and costume designer Masha Kechaeva already had their visas. Under Trump’s immigration, Anna Melnik, the choreographer, was unable to gain legal entry to the U.S. From Moscow, the two women landed in Hawaii. They were picked up at the airport and escorted to the beach where they promptly dove into the bright Pacific Ocean. Says Masha, “It felt like a fresh, deep breath.”

“Oahu stole my heart,” said Viktoria in Russian. A week after the performance, I met with the smiling blonde at the classic Moana Surfrider, the first resort hotel built in Waikiki in 1901. We sat outside, under a large Banyan tree that protected us from the sun and a light rain that strolled overhead. “Honolulu stole my heart,” said her translator, Luba, in English. I could tell Viktoria was passionately telling the truth. She sat up. Her light green eyes flashed.

Viktoria showed me her new tattoo, a souvenir, on the inside of her left forearm. The dusk-colored, geometric line-art design was Suprematist in style, like a Malevich pendulum. The mark came to her in a dream one night in Hawaii during the mad days of rehearsals, community workshops and production prep. Tattooing is very much a part of the Hawaiian and Oceania cultures. Viktoria had hoped to have her skin marked in the ancient kakau method, but such hand-tapping technology is impossible to find.

THE LONG MARCH

In mid-February of 2017, Viktoria Naraxsa and the set and costume designer Masha Kechaeva landed on Oahu and hit the ground running. They were not the first Russians to invade the islands, but the first to depart victorious. (In the early 19th century, Tsar Alexander sought to dabble in Hawaiian politics. The island of Kauai was an easy midpoint between the Russian fur trade in Alaska and the Chinese buyer. Kamehameha the Great united the islands and gave the Russkies the boot.) In addition to the creation and production of a new performance piece, the Russians had a full schedule of community workshops for adults and the keiki (kids) and a fundraising performance at the Arts at Mark’s Garage, a community arts center. In three weeks time, Viktoria’s The Tempest, a conception of William Shakespeare and Masami Teraoka, would debut.

Early on, the program faced many challenges. Language topped the laundry list. Viktoria Naraxsa does not speak the English language. Masami Teraoka is most comfortable in the Japanese tongue. Help came with a call to the University of Hawaii at Manoa. An undergrad pre-Med pursuing a BS in microbiology with a certificate in Russian saved the day. Luba Baydak is also dancing in the AlohaThon Dance Marathon fundraiser of which she is an executive director. Her volunteerism and dedication to the project was exhausting and extensive until it became too much.

SHANGHAI

One of the beauties of an active arts community is the serendipity of the impossible. The prospect and the imagination become intoxicating and a fever breaks out. Let’s put on a show! Over 25 people freely gave their time and craft to the effort. More contributed housing, transportation, meals and the essentials. “No one had any idea how much work it would be,” said Lisa Shiroma, the volunteer production manager. To complete the job, days would be long and nights devoured.

A three-day performance workshop for the Honolulu theatrical community was held at Kapiolani Community College. “Viktoria is an awesome director. A passion driven artist,” said Masami Teraoka, who observed the workshop. “It was too strenuous for even a healthy young (person). Viktoria is tough. I had wondered how much of such physical training would benefit the final performance.” While Viktoria was teaching movement and character, she was also casting performers.

Many of the workshop participants became involved in the production. Tetyana Miyamoto, a Russian who followed her husband to his Hawaii home, attended the workshop and eventually played the roles of Antonio and Trinculo. These parts are traditionally played by men; gender was not a factor in Viktoria’s casting. “I met Viktoria for the very first time at the workshop,” said Miyamoto, “It was a very unusual point of view in creating characters. Implementing movements and action, all action.”

Scheduling rehearsals was difficult. “With work and family commitments,” said Viktoria, “We could only rehearse at night, after their workday.” She laughed, “We all had nervous breakdowns.” The heat and pressure of a production fosters a family, a team of comrades who accept the challenge to create a work of art to the very best of their abilities. “The actors and production crew have been working around the clock to create this performance,” admitted Lisa Shiroma. “The stress brought us closer,” said Viktoria, “In essence, we were taking on a large project, like building a house.”

Religion has a presence throughout this narrative. In New York, Nadya and Viktoria were staying in an apartment in a former Catholic cathedral when Masami Teraoka first contacted them. Pussy Riot and Teraoka share a conceptual interest and work history in cathedrals. It is not surprising that the first Hawaii rehearsals took place in the chapel at the University of Hawaii at Manoa.

With a financial budget limited to essentials-only, the entire performance was a volunteer effort. Says Masha Kechaeva, “We had the greatest team ever and I’m very grateful to all of them. A magical crew… (It was) the most organic thing, if you’re open, it brings you amazing people to work with, it gives you meaningful stories.”

AN ARTIST’S INFLUENCE

For Viktoria, everything about Hawaii became a mind blowing new experience. Like a “love at first sight,” Koko Head Crater, an extinct volcano east of Diamond Head, overwhelmed the director. She wanted to stage the play inside the green mountain arena. The experience would have been staggering. Unfortunately, Hawaii is a land of many permits, red stamps and slow permissions. That idea was given a fast nyet. She smiled and said, “You can’t fake love.”

“The show had grown into a major production!” said Lisa Shiroma, the gung-ho production manager. Masha, the set and costumer designer said, “It was quite a unique experience because in my regular life I draw sketches and then the production team makes [the costumes] real, according to my drawings. In this type of production, like The Tempest, I had one sewing machine and two days to sew eight costumes. It was a journey!”

FORGIVENESS OR PERMISSION?

Besides the deadline, the only other certainty of the production was the use of the Linekona, now known as the Honolulu Museum of Art School. Built in 1908, the tall two-story Colonial Revival is an imperious grand dame. However, the landlord is a very conservative arts organization. Masami Teraoka was given permission to use the lawn and the sweeping steps in the front of the building. Who could say no to Hawaii’s greatest living art star? As legend goes, Viktoria Naraxsa took one look at the Linekona and wanted more. She saw great possibilities. The Teraoka Team asked for additional permission to use the interior lobby and it was granted. Like a tempest in a teapot, the director’s ideas kept burning and consuming ground. In short order, the whole building was invaded like Putin snatching the Crimea.

Rehearsals were fluid exercises as the concept and script were being written on the fly. Slowly, it was designed that the audience would break into two groups and move in sync throughout six staged areas or rooms. “We created a story which invited local people to have an experience altogether and to become one team in the process of that discovery,” said Masha. Two groups would see different narratives. Then the audiences would congregate to watch a ceremonial video sequence and then move to the balcony outside for the wedding banquet finale. The rehearsals were taxing for the talent. According to Viktoria, “The three weeks went by in a second.”

Time flew with seconds to spare. Viktoria was absorbing Hawaii. As a choreographer, she did not have enough time to adequately pursue her interest in haka, the native New Zealand war dance or the aggressively precise and athletically demanding Hawaiian men’s hula. She forged a quick immersion into the local arts culture, meeting, among others, ukulele virtuoso Taimane Gardner and Jonathan Heraux, founder of the Ong King Arts Center. Somehow, Viktoria even got a tan. She desperately wanted to learn how to surf.

“Now when I look back,” writes Masha Kechaeva, “I see the whole month in Oahu as an immersive play itself, where I was the viewer, actor and director in my regular life. The concept of “being immersed” turns into the way to see the reality. [Life is] a symphony and every musical instrument has its own role, you as viewer pay attention to every sound, detail and unexpected thing.”

FLIPPING THE FUNDRAISER

Damnably, this Pussy Riot posse did not burn down any institutions or desecrate our altars. Nary a palm tree was torched. Nonetheless, these creatives did upset some local notions. Hawaii is largely xenophobic and justifiably so. Captain James Cook set the bar and every well-intentioned invader has been raising it since. Hawaii has a fear of strangers and Viktoria Naraxsa pinched that notion in their ʻēlemu, or their keister. In addition to conceiving and producing an undefined performance in three weeks time, the Russians had to create a fundraiser for The Tempest. Forty or so good citizens arrived at the Arts at Mark’s Garage, an art space in Honolulu’s Chinatown, expecting a solo dance performance by the exotic Muscovite. Hardly. The audience became the performers. Quite cleverly, the audience was forced to confront their xenophobia and experience the love of a stranger. Titled Close, the audience members were paired with an unknown. A questionnaire unveiled the assumptions of the other. One was blindfolded and the other gagged. The new teams were forced through a series of rooms, exercises and communications. Most horrifying, they were asked to dance together. Once unbound, a new Q&A made light of their previous prejudices. The evening was concluded with a toast and a glass of champagne. One witness confessed, “Many new friendships were made that night.” Now, that’s Aloha!

Pussy Riot, in all of their glory, are hell-raisers, saboteurs and nose tweakers. All hard work demands a little play. Viktoria and Masha caused a small kerfuffle at the VIP opening of the first annual Honolulu Biennial. Had this provincial burg been Manhattan, the indiscretion would have made tabloid headlines. The generous Howard Hughes Corporation is the major donor to the Biennial and their iconic Vladimir Ossipoff designed headquarters is one of the many sites in the exhibition. The 1962 modernist masterpiece was exhibiting a sublime Yayoi Kusama Infinity Room. Never get a Russian near an open bar. It has been whispered, never stated, that Viktoria and Masha were raising hell and taking selfies on Kusama’s polka dotted bed and clamoring at her polka dotted dining table.

In Part 2, tensions mount as the debut approaches. A backstage romance blossoms. An epic meltdown halts production. The Pussy Riot partisans, performers and local talent hunker down as the curtain rises.

All photos by Neal Izumi

_______________________

Gordy Grundy is a Pacific-based artist. His visual and literary work can be found at www.GordyGrundy.com