I hadn’t sent the novel out in a while. In fact, I hadn’t sent it out in months. What was the point? Even if they loved it, they didn’t want it. At this point I was too dispirited to send the work out or describe the ensuing demoralization. But I needed to send it out in order to have some fresh rejection to write about. Otherwise I had nothing to say, and with these exaggerations and fabrications, I was only perpetuating frustration, laying a false trail across the visceral ether.

I sent the same fifty-page section that Melinda Waterform had ignored to Jim Brooklinen, a former editor of The New York Times Book Review. I had enjoyed a warm acquaintanceship with this eminent old East Coast literary man for about ten years and he had always encouraged me in my modest endeavors. I had been reluctant to send him the novel, or any portion thereof, as I had heard him complain about the unsolicited works that were still inflicted on him by pushy writers when he was retired and declining in health. But during the course of our occasional correspondence he had asked to see the novel when I had told him what I was working on.

“Dumb up the volume, because if you turn it down the quality of conversation will have to rise,” I said to Eden Gaperdiveve when I encountered him in a popular bar on the eastern end of Sunset Blvd.. A deejay was blasting classics from the halcyon punk and post-punk era – vicarious nostalgia for today’s youth, who hadn’t found anything better to replace it with.

“At least he’s playing good music,” said Eden as a highly compressed wave of negative elation—Mannequin by Wire—surged through the small room. Eden was a charming and erudite young man of letters. He ran a small press and arranged some remarkably democratic literary events around town. He seemed to care.

“That’ll be nine dollars,” shouted the bartender as a tattooed hand placed a bottle of cheap Mexican beer in front of me.

“I’m sorry.”

“Nine dollars!” he barked back.

“I didn’t order two, just the one!” I shouted back, and grudgingly threw down two fives, resenting the one dollar tip. This was a high price to pay for the privilege of having one’s senses assaulted in a claustrophobic sty filled with young people who were learning how to drink, learning how to smoke, learning how to hold a cigarette properly. Ten years ago the bar was a hole in the wall with a curtain in the doorway, and it was off-limits to well-heeled young Caucasians. Never mind…

“I’ve really been enjoying your rejection articles, especially that last one,” said Eden.

I thanked him kindly.

“It was funny,” he said, “but sad too.”

“Tell me about it,” I said, taking a sullen two-dollar slug of the overpriced beer.

“I’m glad somebody’s taking a roman-a-clef approach to the local literary scene,” said Eden. “I dug the Jeff McClimon cameo.”

“What’s that?” I said, straining to be heard over the chorus of Chinese Rocks.

“The writer you ran into outside your apartment. That was Jeff McClimon, right? It had to be.”

I was flattered that somebody was paying attention enough to make such assumptions, but also slightly disturbed that the character had been identified so easily when I hadn’t revealed anything specific about McClimon. “Jeff could easily recognize the encounter it’s based on,” I said. “I don’t suppose there’s much danger of him reading it though. He probably has better things to do, like his own work. How did you figure that out anyway?”

“He’s local and he wrote a blurb on the back of Neville’s book,” said Eden.

“You’re too sharp for your own good,” I yelled back. “What makes you think that was Neville’s book?”

“Because you were complaining about it when we were talking about Alt-Lit a couple of weeks ago.”

“Not exactly,” I lied. “It’s a mishmash, a composite. Most of these characters are composites. Situations and sentiments get transposed and shifted around. It’s taking shape as we speak.”

It was true, however, that the earlier-derided Alt-Lit author, Zander Valvitcore, could have been based on a number of people, not just Neville Smirek. The literary world currently abounded with self-published, micro-press-published—and increasingly, major-press-published—transgressive young writers. It was strange, but in recent years becoming “a writer” had come to be seen as a glamorous occupation, especially for inexplicably affluent young people who had nothing else to occupy their time with, and such writers as Neville Smirek were encouraging this new perception with their phantom income-fueled globetrotting lifestyles and aggressive social media presences. They threw publication parties in nightclubs that were more like raves than literary events, surrounded themselves with models and ‘influencers’, and ingested copious quantities of molly and other designer drugs. These salons and soirees were instantly over-documented on Instagrim for the convenience of the uninvited and the hateful doom-scrollers among us. Which would all be fine, if the writing itself was any good. Which it usually wasn’t. These days there were simply a lot of people that liked the idea of being a writer; they thought of themselves as writers and described themselves as such on their social media profiles, although there was very little writing going on compared to the amount of time they spent hustling and being fabulous. But the effortless enablement of the internet made it possible for them to entertain such illusions.

Edward Kienholz, “Barney’s Beanery,” 1965.

“Why do you even care?” said Eden.

“I resent people that haven’t made the same futile sacrifices that I have,” I said.

“Because they haven’t paid their dues?”

“Something like that… since when was the deejay elevated to the status of priest? This guy isn’t even spinning records. He’s playing music off a fucking laptop,” I said, deliberately changing the subject. Although I objected on moral and syntactical grounds to some of the authors he handled, I wasn’t entirely opposed to the possibility of being published by Eden’s emerging press: they were getting some favorable attention and had decent distribution.

“Let’s go outside so I can smoke,” said Eden.

We walked through the crowded bar to the crowded but somewhat quieter sidewalk.

“I was just talking to Suer,” said Eden, lighting up an American Spirit.

“I’m sorry…”

“Emgona Merage’s husband.”

“I thought she was a lesbian.”

“She is, but now she’s married to Suer Wightman, who just transitioned. They are a writer too.”

“Naturally.”

“They just wrote their first novel but they can’t get it published, which is funny because Suer is represented by Charlie Byars.”

“Never heard of him.”

“Really?” said Eden in disbelief. “Charlie Byars is one of the biggest agents in the country.”

“Like I said, despite the endless bellyaching in the articles, I haven’t really made an honest effort to get my novel out there. I just like complaining about it. How come this Suer person is represented by such a big agent if it’s his first novel?”

“Charlie Byars represents Emgona Merage…”

“Right. I see… So he’s represented by the biggest literary agent in the country, he’s married to a highly successful young writer, he just transitioned, and he still can’t get his novel published.”

“That’s right,” said Eden.

“Very odd,” I said. “He’s made all the right moves. A rare case of nepotism not working. Maybe the novel is crap.”

“I’d be very interested to read it,” said Eden.

“Why?”

“I’m really curious to see what it’s like. I mean, maybe it’s great. I’ve been asking them to send it to me for months.”

“Why, because it keeps getting rejected? That’s a great reason to want to read something. It’s his first novel, and the only reason it’s handled by a top agent is because they represent his wife.”

A photogenic young poetaster approached us, or rather, approached Eden. A conversation sparked up between them on the subject of a mutual friend’s new book, and I receded quietly from the picture.

Despite professing to greatly enjoy everything he’d ever read by me, Eden hadn’t asked to see my novel, yet he could hardly wait to get his hands on the rejected novel by Emgona Merage’s husband, Suer Wightman, doubtless with a view toward publication… because it had been rejected by numerous other publishers. If rejection was such a mark of potential quality, why then not ask to read my novel? Because I hadn’t married well and I hadn’t been rejected by the right people. Eden seemed to care, but what he cared about was a matter of some concern. As I walked away, such tiresome considerations began to gnaw at my vitals.

All this stress and bitterness was the direct result of being involved, however marginally, in the literary world. If I didn’t write, then I wouldn’t have to complain about not being read. A little appreciation would, of course, go a long way towards improving my attitude.

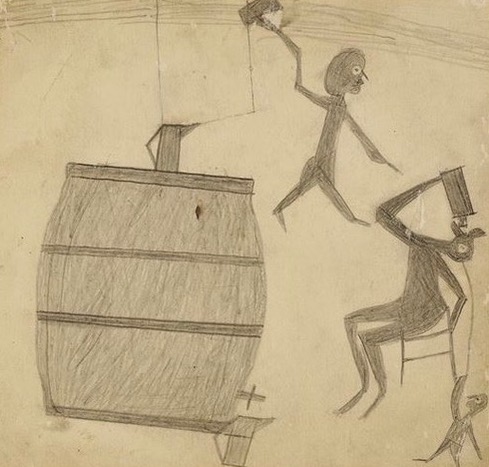

Bill Traylor, Untitled, 1934.

“John—I’ve read the excerpt you sent me, and I think in texture, sentence-by-sentence, it is often—generally—quite brilliant. There are sentences and small touches of (often splenetic and/or self-loathing) geniud scattered throughout, and the general precision of this voice is pretty extraordinary. The whole thing—this, and the rest of the book, depending on its nature and consistency and progress—may well be publishable. I do think that the overall misanthropy and self-flagelating may be too relentless for some readers. But I want to emphasize that the writing her, word- y-word, sentence-by-sentence, etc., is a really original and impressive achievement. Let me know whennyou think you’ve got the whole thung in shape, and I will do what I can to help you. As always, it was very good to hear from you.”

That was more like it. Within less than a week I had received a response from Jim Brooklinen. Jim had edited Elizabeth Hardwick and enjoyed weekly luncheons with Mailer in the seventies, so his response was tentatively validating. Failing eyesight could probably be blamed for the uncharacteristic litter of typos in his email, and he had somehow formed the impression that I’d sent him an extract from a work in progress rather than from a finished novel, but I could rectify that misunderstanding and offer to send him the entire manuscript. His response gave me a sorely needed lift.

“What have you been up to lately?” said Eden Gaperdiveve when I next ran into him.

“Just the usual round of bullshit. Nothing of substance, I can assure you. I’m still writing those articles.”

“That doesn’t take very long, does it?” said Eden.

“You’d be surprised,” I said. “The level of production may not seem justified considering the general indifference and lack of reward. It’s absurd on every level but…”

“Well, I’m enjoying them,” said Eden.

“You’re really going to enjoy the next one,” I said, somewhat sheepishly. I’d been wondering how to break it to Eden that I would be using him towards my own disreputable and self-serving ends.

“Why, am I in it?”

“Yeah, sorry about that. It’s not offensive. At least, I hope you won’t be offended by it…” I waffled on. Eden was an affable sort and I felt guilty about using him in this way, but he had furnished me with some rich material and I couldn’t seem to stop myself.

“Just as long as it’s not a hatchet job like with Tiffany Hardinskin,” he said, referring to the celebrated writer of ‘literary fiction’ that the Melinda Waterform character was loosely based on: a not entirely gratuitous slur on the over-revered.

“Don’t worry about that. You’re just a vehicle. There will be a few digs but it’s purely in the interest of moving the narrative along.”

“You hang around with writers, you’re going to get written about,” said Eden, shrugging it off. “I accept that.”

“Really, don’t worry about it,” I said. “Nobody’s reading it anyway.”

That was a relief. Eden didn’t seem to mind at all; he even seemed a little pleased about it. But he hadn’t read it yet.

This is Part VII of an on-going series. Please see previous installments: Part I, Part II, Part III, Part IV, Part V and Part VI.