I don’t know how to create the impression of time passing. But it passed, weeks passed by, during which nothing much happened.

The sense of futility engendered by these dealings with the literary establishment hung over other potential undertakings. There didn’t seem to be much justification for this ongoing expenditure of waste, otherwise known as literary endeavor.

More than four years were spent writing a novel that remains unpublished. It’s unlikely that I will ever do anything better. I’m not getting any younger, and I may not even get much older. Under the circumstances there doesn’t seem to be much point in transcribing or describing anything anymore.

At this late stage of my brilliant non-career my chief motivation for engaging in this time-consuming and sadly only self-indulgent pursuit is to satisfy the insatiable demand for new material that will inevitably follow the runaway posthumous success of the novel in question, in the form of a slim companion piece. Although in my case posthumous success has become such an obvious irony that even that ice-cold compensation will probably be denied me.

Meanwhile, the Mark Eupoles and Jeff Dryers of this world churn out one book after another, secure in the knowledge that the slightest squirt from their golden pens will be preserved for posterity: a volume of adulterated juvenilia, a collection of essays on tennis, a miniature novella tastefully packaged as a single hardbound volume with embossed silver print on a black background and sold as an expensive signed limited edition. For these elite authors one undertaking automatically leads to another, with publishers always at the ready to distribute their latest wares to an eagerly awaiting public.

Appalled as I was by the prospect of using others to advance my cause, I was slowly being forced to arrive at the unpleasant conclusion that there was no other way. I couldn’t do it all on my own: I could produce the work but after that I didn’t know what to do with it.

Casting my mind around for influential acquaintances that might be willing to help, I lit on the prospect of my illustrious neighbor, Melinda Waterform, who had become something of an overnight literary sensation following the publication of her novel, The Habit Of Desire. She seemed to find me amusing but had never read my articles, despite my having urged her to do so, and despite our having reviewed, on several occasions, the same books—and despite my reviews being more entertaining and insightful than hers, which were now gathered in a collection published by one of the big houses, with a color photograph of her looking insufferably content on the dust jacket.

I frequently encountered Melinda when she was walking her dog around the neighborhood early in the morning, and sometimes we briefly chatted about her career. It would be opportunistic of me to approach her, especially as I had never read any of her novels. I couldn’t fathom what somebody who led such a seemingly idyllic existence—thriving career, financial security, happy family life, property owner, frequent travel, grants, residencies, ad nauseam—could have to write about. But writing wasn’t all about complaining, and from what I’d heard she was particularly skillful at fashioning compelling narratives out of calculatedly relevant contemporary subject matter. If her work was bad, it would annoy me. If it was good, it would annoy me even more, so I didn’t read it. But perhaps she might look kindly enough upon me to suggest an agent that I could hit up. After all, we were neighbors.

I balked at the prospect but steeled myself to gently petition her upon our next encounter, if she wasn’t already talking loudly on her cell phone, as was usually the case.

All disingenuous bellyaching aside, it wasn’t as if I was bombarding publishers and agents with multiple emails. If, as it has been said, one should put as much time into seeking publication as one does into writing the book itself, I was coming up short, very short. I hadn’t waged an intensive campaign to get this thing published; I had only made sporadic, half-assed attempts, and I had been too easily discouraged. It wasn’t in my nature to aggressively pursue publication, or anything else for that matter, and I needed my remaining diminishing reserves of energy for the work itself.

But perhaps this lack of effort resulted from an innate sense of hopelessness in the face of the crushing and chastening business of dealing with the publishing industry, especially in this day and age of strictly monitored content and preferential handling. There really didn’t seem to be any way in. Arriving unsolicited at a publisher’s door, you might as well be trying to sell them vacuum cleaners.

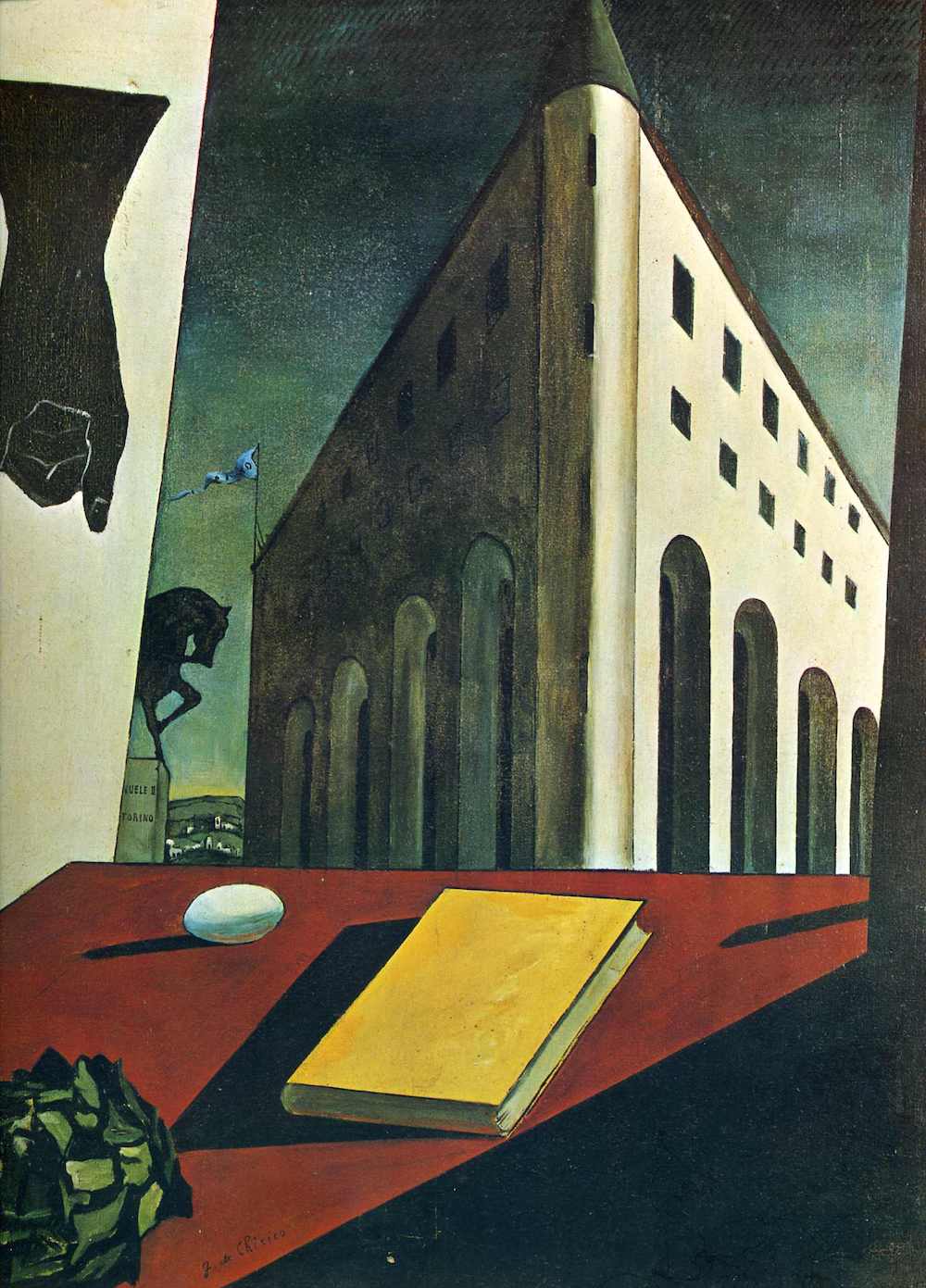

Giorgio de Chirico, Turin Spring, 1914.

You might as well be trying to sell them fucking vacuum cleaners.

“Where’s your dog?” I asked, unable to come up with a better conversational gambit, when I encountered Melinda Waterform waiting at one of the interminable stoplights on Sunset Boulevard.

She put on a brave smile, bracing herself, no doubt, for an awkward and preferably brief exchange. “He’s at home with the children,” she said, sounding tired, and announcing the presence of something she had in her life that I lacked, and didn’t want.

“On the subject of dogs,” I said, “you should read my recent article on the subject in Artillery.”

“Oh, really?” she said, with a show of curiosity that sounded a lot like disinterest. “Do you have something against dogs?”

“I have something against noise,” I said. “It’s more about dog owners than dogs. It was inspired by an encounter with an arrogant dog owner in the neighborhood… not that all dog owners are arrogant,” I quickly added. Talking to Melinda had never been easy and now that I was going to be asking her for a favor, everything I said to her sputtered forth more clumsily than ever.

“I’ll read it,” she said, glancing anxiously at the unchanging Don’t Walk signal on the other side of the busy street. “How are you otherwise, doing good?” she asked, probably not expecting an answer, least of all a sincere one, as she pressed the Walk button.

“You know I wrote a novel,” I said.

“No, I didn’t know that,” she said, with a strenuously patient half-smile, as the countdown on the Walk signal began to flicker.

“Well, it’s not exactly common knowledge, but I did, and now I’m trying to get it published, and…”

The words came out flat and foredoomed, lacking conviction in the awareness of their ultimate futility. The Walk signal lit up, but Melinda raised her eyebrows and paid me the honor of waiting the light out.

“… do you know of any agents or publishers that might perhaps take an interest?”

“Well…” I watched her weighing the situation, with the overloaded scales tilting heavily against the desired response: “… I suppose I might have some ideas.”

The traffic continued to pour by. After a long ten seconds, she fixed me with her exophthalmic and Listerine-colored eyes and spoke very directly: “I’ll tell you what, I wouldn’t normally do this, but I’ll do it because you’re a neighborhood character. Send me a PDF. No, send a couple of chapters or whatever.”

“How about the first fifty pages.”

“That’s fine,” she said.

“Tonight, yes, I’ll send it over. Thanks.”

The Walk signal lit up again, and this time Melinda didn’t linger.

John Currin, untitled.

As I walked away, I suddenly felt very small, my obscure position thrown into harsh relief. My hopes were raised, but it was not a pure sort of hope; it felt tainted and fleeting. Melinda’s disinclination had been palpable. She had no idea as to whether my writing possessed any merit, and didn’t seem interested in finding out. She assumed, I assumed, that owing to my age, social standing, and lowly station in life, that she had nothing to gain from bothering with it. And she had her own work to do: I understood that.

Nevertheless, I spent the evening editing a few passages together for her delectation. I harbored grave reservations about sending the work, or any portion thereof, to Melinda. She would now be privy to the contents, and could freely blurt about them to other literary friends of hers, perhaps in a disparaging manner; she could steal my ideas—she seemed like something of a literary magpie—or give them to someone else. She could also completely ignore it. None of these options were very appealing, but there was also the slim chance that she might be impressed enough to help me secure the services of an agent, although this seemed the unlikeliest of all these possibilities.

I sent her a modified version of the first fifty pages.

This is Part V of an ongoing series. Please see previous installments: Part I, Part II, Part III. and Part IV.