If one thinks of the essence of Modernism as being about direct experience rather than recreated experience, the artist who has really continued to expand possibilities is James Turrell. A striking aspect of his retrospective exhibition at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, which fills one whole floor of the Broad pavilion and a large portion of the Resnick, is what a personal experience viewing these works can be. This is especially true of the Perceptual Cell piece titled Light Reignfall, in which the viewer, laying flat on a narrow bed, is injected into a room-sized sphere. With no sense of actual space, the initial impression is that one is on top of a hill staring up at an unclouded sky. Then the color slowly shifts and a series of patterned images explode in vibrant hues, creating an intensely optical experience. The visual effect has great affinity with “inner” kinds of imagery, such as the patterns one sees with eyes closed, or those induced by hallucinogens. It is often difficult to distinguish whether one’s eyes are closed or open—actual seeing has been converted to the way we see on the screen of our mind.

One reason the Perceptual Cell works so effectively is that only one person can experience it at a time; the piece lasts for 12 minutes, and one is completely isolated inside the sphere. This is, of course, not true of the other installations in the show—there are almost always other people around. Being one-on-one with the artwork is a very special experience, one that we don’t have quite as often with contemporary art as we used to. No distractions or voices, just you and the art. Unfortunately, admission to that one work is booked through the show’s closing in April, but the remainder of the show is a marvelous experience as well.

It is, in fact, surprising that Turrell’s work has become so popular. His 1985 retrospective at MOCA Los Angeles was, by comparison, very sparsely attended. That so many people have, in the intervening years, become interested in what is still a rather esoteric kind of art is a testament to a growing interest in contemporary art by the public at large. This seems like a good thing, especially in the case of Turrell, because a quiet, contemplative art that engages viewers’ perceptions directly (“you see yourself seeing,” as Turrell has often stated) is a great foil to the cluttered and distracting world we now inhabit.

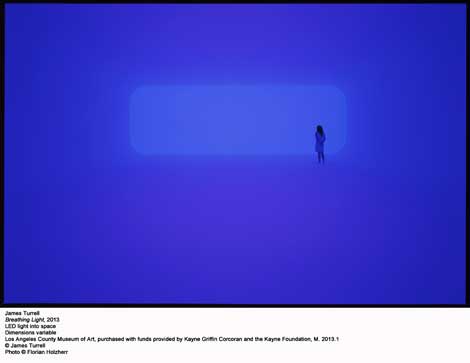

The other outstanding installation in the Resnick Pavilion is Breathing Light, one of Turrell’s Ganzfeld works. Ganzfeld, which is German for “entire field,” refers to the ganzfeld effect, the hallucinatory optical phenomena that occur with perceptual deprivation produced by exposure to an unstructured, uniform stimulation field. Breathing Light is a walk-in installation in which visitors enter a large space in which the corners have been rounded, so that no sense of the room’s perspective is apparent. On the opposite wall from the entrance, another space in a second room has a completely rounded off interior, so that it first appears to be a monochrome painting on the wall. The colors shift on the entire piece, so that it is constantly changing in a very subtle way as the viewers, wearing paper booties to protect the pristine floor, walk around the space. The effect is impressive, although the Perceptual Cell actually seemed to create an reaction more akin to sensory deprivation; in Breathing Light one is always aware of being in a real, tangible space.

The remainder of the show includes a large section documenting the Roden Crater Project that Turrell has been creating in the Arizona desert since 1975, and several recreations of earlier light installations, beginning with the projections from the 1960s. These are wonderful to see, since they help to chart the development of the artist’s work, as in any retrospective. What cannot be recreated is the moment of perceptual ambiguity when for the first time one experiences a Turrell installation that mimics the effect of a minimalist painting hanging on a wall. I saw one at the Flow Ace Gallery in Venice, California, in 1983, knowing nothing about Turrell’s work, and will never forget the moment that my perceptions were turned inside out. All of one’s expectations about the flatness of the surface one is looking at are pulverized in that one perception-changing instant. Unfortunately, no installations of that kind were included in the LACMA show, possibly because they deal with illusion, not direct experience. They are amongst his most austere and powerful works.