Many collectors are the most influential people you’ve never heard of. Not so Stefan Simchowitz, the art collector who has been dubbed the “art world’s patron Satan” (New York Times Magazine), “the greatest art-flipper of them all” and “a Sith Lord from the Brotherhood of Darkness” (Jerry Saltz on New York Magazine’s online blog). Seems like every art magazine or critic has posed the question around Simchowitz—does he or doesn’t he?

Born in South Africa, Simchowitz received a B.A. in Economics from Stanford, attended the American Film Institute in Los Angeles, produced 15 feature films including Requiem for a Dream, and co-founded celebrity photo and video service MediaVast, which Getty Images bought for $200 million, all before becoming an independent consultant/curator/strategic cultural entrepreneur in the art world.

He buys artists early and in bulk, often getting to them first. He values his own collection of about 1500 pieces of emerging contemporary art at around $30 million. He’s been blacklisted by galleries but has found ways to get what he wants anyway.

I spoke with Stefan Simchowitz by phone from New York. I envisioned him prowling along empty Westside LA streets as we talked, since between his plummy accents he was panting.

Artillery: It seems you left the film industry right around the time LA stopped being just a film company town, and also started being the West Coast art town.

People like to have these absolutes, like it’s binary: it goes from a to b, black to white or blue to green, but I don’t agree. It doesn’t. Its like a floral arrangement; they put the roses in, then the tulips, then the greens; they’re just adding more flowers to the city, and the city’s becoming more vibrant and more colorful, eclectic and diverse, and more powerful in its diversity. I think that’s what’s interesting. The film business is so central to LA and always will be. The film industry has become much more interested in the art industry. The art industry has always been interested in film; they’re just getting closer together. And in proximity, they can begin to learn from each other, they are learning from each other in LA in a way that’s quite unusual, in the respect that the way film content and film culture are distributed and manufactured within the Hollywood system has so many interesting attributes, so much talent and, frankly, decades of experience building the Hollywood system, that is still today the preeminent system for cultural production in the world. The art business can perhaps learn a lot from it and Hollywood, vice versa, can learn a lot from the art production system, in how art deals with ideas, concepts and has a worthy respect for the narrative of ideas and the complexity that ideas bring to society and culture. LA’s like this perfect marriage of these two industries. Of course, the one’s always been dominant, but art is coming to gain its own foothold in the community.

So you brought a lot of experience in distribution and distribution channels to the art world.

I began in the movie business. I’m from South Africa; I went to Stanford undergrad. At Stanford, I watched movies every single day. I had a laser disk player, and I would literally watch a movie to two movies every day. Probably did it for five or six years; I watched hundreds of movies. It was a revelation. I watched Japanese cinema, French New Wave, the noirs, and really systematically, the westerns, the revisionist westerns of the ‘70s, the Eastwood westerns. You build up a huge cinematic language. There’s a dealer in New York named José Ferrer that I have a particular love for because he has such a great knowledge of cinema and film. I really think that the language of cinema has been critical to me in understanding things, and also my experience in building a business as a young producer in Hollywood helped form many of my ideas and strategies, methodologies as to how I function today as a collector, patron, dealer, curator, a sort of hyphenate within the art industry. I have great reverence for what the film business gave me, in its entrepreneurial skills.

So you’re still a producer, in a way.

That would be one way of putting it elegantly.

It sounds like you’ve worked hard to educate your eye, but your dad was a collector, right?

And my mom was an artist. I’ve had a love for photography since I was 15 years old. I’ve taken pictures and I’m very proud of them; you’ll notice them all over my Instagram account. I would have loved to have been a photographer, but I could never find the will to behave in that way, to secure jobs and be that individual. But taking pictures since I was 15 years old, literally almost every day of my life, I see the world through images, crafted through my understanding of film, my understanding of the power of images. The amount of experiences I’ve had throughout my life position me, in a strange way, perfectly for this moment, where social media comes along and gives me an outlet for the specific way in which I communicate, which is through images and the sharing of information that’s intellectually interesting to me. Social media is a perfect way for me to publicly diarize my life, and share things I couldn’t necessarily—you can’t really go to a magazine and say, “Hey, here’s photographs of my kid, do you want to publish them, aren’t they beautiful?” But they’re very interesting to me, and that journey’s interesting to me, and I take great care documenting them. Images are so central to the way that I think and behave.

How much sleep do you get? I saw one of your long Facebook posts at 3:45 AM.

I was in Australia, in the Blue Mountains. But the strange thing is, I’ll have an idea that will percolate in my head and I’ll suddenly just want to get it out and I’ll sit down—that was a 3,000-word post—and I’ll write that in 10 to 15 minutes, one sitting. Once I’m in the zone and I’ve thought about things, it just sort of flows out. A lot of these conversations, I miss certain things, clarify certain things—I like the dialogue that ensues because it enables me to think through the ideas. Sometimes people disagree with it or attack it, and I answer them in a way that answers a lot of the holes in my original argument, or even think through things that I haven’t thought through properly, which sometimes helps change my opinion of things. I’ve met a handful of people through social media, who I’ve never met in person, who have been an absolute enlightenment to me, in my thought processes and in witnessing their clarity of thought. One is a guy named Robert Keil.

I liked what he said about the combination of your eye and your understanding of economics making you a force to be reckoned with.

Some people have what I call “clarity of vision.” They’re able to distinguish the leaves from the bush, and the bush from the forest of trees. They have clarity, unencumbered by the weight of their own baggage. I enjoy it when these people come into my life, and do so through such a random, open environment as Facebook.

How do you feel about democracy?

I’m a great believer in democracy. I believe in diversity. I believe in the power of different voices coming together; I believe in the conflict that those voices bring against each other, creating balance and imbalance in the system. I think conflict is part and parcel of the condition of human evolution, so I’m a huge believer in democracy and its constant state of flux. That’s a strange question to ask me.

A democratic approach to the art market plus social media—I think you’re saying it equals evolution.

The art business has always been democratized to a degree, and it just becomes a more interesting democracy as the participants become more diverse and there become more participants. I don’t think it was an undemocratic environment before, I just think it was an environment that had fewer players and hence less diversity and so less of an appearance of being democratic by its lack of diversity and its sheer reduced volume. Now there are so many voices that come to it in such great volume that, compared to what it was in the ’50s and ’60s, it’s far more democratic. And the entry point for people to engage in art or have a conversation is completely different to what it’s been. These things have been facilitated by the ability to communicate easily—mobile telephones and social media—and I like it.

Didn’t that become a sort of illness, especially in New York, where the aperture kept getting smaller and smaller as artists were just focusing on producing for the rich?

And no one cares, so you just have these institutional paradigms. It’s a complex issue because the art world tends to frame things through a very specific moral and ethical lens, tailor-made to suit the structure that the art world has built, specifically in the postwar period. And it’s now really getting challenged at every corner by a much more mobile, flexible system of operating.

What is Simco’s Club, and how is it a new model?

I don’t really believe in new models, I just believe in a more productive way of doing the same thing. I’m not reinventing the wheel: it’s a really simple website—just aggregates my newsfeed from Facebook and Instagram, and people can get a general idea of what I do and what I’m about, see some notable press, and I sometimes send out a funny newsletter/shitlist/hitlist. It’s not really a business, Simco’s Club, it’s just a communication tool. I don’t think many people really go there, it’s just for convenience; most people still experience my shenanigans through my Instagram or Facebook page.

It’s something we’re already accustomed to, matching buyers with content makers, so why the big backlash? It’s like when Dylan went electric. What is this huge bunch of hate mail around your work?

I have no idea. I invest every single penny I make in art, I take risks and invest money and spend money on young artists, and as I get older and more seasoned, I don’t look to collect older artists like Richard Prince—and I don’t mean that in a denigrating way—but as a “graduate,” most people look to collect Warhol or Richard Prince. I don’t. I believe in young art. I believe in Emerging Contemporary as a category. I believe we live in a golden age of art production. There is more funding for art production, education for art production, more collectors for art production than ever before, and I think we’re in a sort of Renaissance of art. As opposed to some conversations I’ve had: “But there’s so many artists; there are thousands. It’s terrible; I’m going to collect more blue-chip work.”

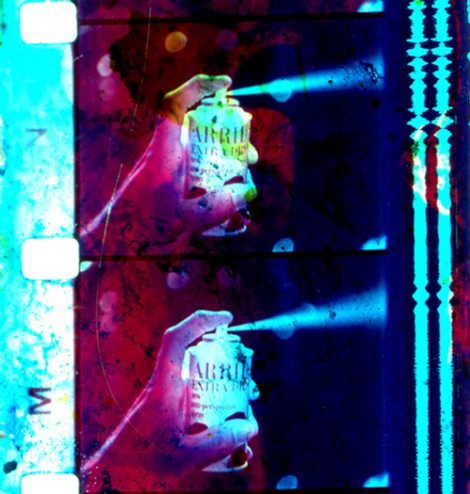

JENNIFER WEST, Arrid Extra Dry 1965 TV Commercial Film (16mm film print painted with birth control pills, writing inks and sweat – bought from a Brooklyn, New York street vendor) 2013

I made a joke recently that if I’m a donkey, I’m collecting tails because they’re pinning the tail on the wrong donkey. I think Jerry Saltz had an idea of an archetype of the kind of collector or individual I am. What’s ironic about what Jerry Saltz writes—I relate to Jerry, I think he’s a great writer; I like him, I like his thinking, but without meeting me or coming to see me or interviewing me or talking to me, he kind of pinned the tail on completely the wrong donkey. So everyone else was like, we’re actually the evil speculator that Jerry’s writing about, but guess what? He’s got the wrong guy for the crime, and this guy seems be able to take it pretty well, so we’ll let him collect all the tails for us and we can scurry about doing our business under the pretense of being the good and the great, the decent and the moral, the ethical and the fearless, and Simchowitz can be the whipping boy and take the heat.

What’s the Depart Gallery?

It’s not a gallery, it’s a foundation run by Pierpaolo Barzan, who started it in Italy over 10 years ago. I was a strategic consultant for his foundation for a very long time; he’s a client of mine, a collector, a wonderful guy. He wanted to leave Italy and come live in Los Angeles. We slowly came together and he opened the project space in LA. I am all about supporting art across every category. I think Depart Foundation has this in its mission, and I’ve been very supportive of the foundation in achieving those goals.

Do you buy art you like?

I only buy art I like. I only manage art that I like. I only sell art that I like.

What do you like right now in LA?

I’ll tell you something I bought recently that not many people know. I bought a ceramicist, an artist named Jeffry Mitchell, who I think is in his mid-50s. He makes these uniquely heavy, large ceramics. I bought them from a gallery that closed, Ambach and Rice, and I love them. That’s something LA that’s something I like, Jeffry Mitchell.

Something else I like that’s not obvious? We have a lot of good art. Someone else I’ve collected a lot of work from and placed a lot of work for is Jennifer West, who I think is an amazing mid-career artist and totally underrated from a market perspective. She does a tremendous amount of great video work, and she does these amazing filmic prints. She’s someone who I think you would be surprised to find that I like, but I’ve collected her quite heavily.

What does it mean to have an eye, and can you cultivate it, or are you just born with it?

You’re born with it, but if you don’t cultivate it, it will not develop. Art is so pregnant with emotion and taste. I know collectors who have good eyes; I can tell the difference between them and collectors who don’t have eyes. Collectors who have good eyes might have collections I would never collect myself or like, but I know they’ve got a good eye. But you immediately enter the moral hazards of the business and the quagmire that surrounds it when you start discussing these things—because if you meet any collector, one of the first things they’ll tell you to justify their collecting values is: “I buy only what I love, therefore I’m a moral collector.” But often times you can see that what they love is like a stuffed rhinoceros head on their hunting cabin wall or a huge painting of some crazy scene in gaudy colors in red and pink purple—hideous—but they bought it because they loved it, therefore it’s good and they’re collecting under the correct moral procedure, buy what you love.

This discussion of how we choose to frame the art world from a moral perspective is one of the central themes I find really fascinating, and the one macro theme that I’m really interested in challenging, understanding and discussing in the art world. If we can really come up with a system to question these belief systems, we can come up with a much more productive and much more ethical art world that benefits the values of everyone involved, artist collector dealer curator institution, and if we can just attack these problems we could end up with a solution that’s really in the best interest of everyone, what I call intelligent decision-making: decisions that benefit everyone involved.