Although Christopher Reynolds’ art is full of food imagery, few of his installations and performances traffic in actual foodstuffs. “It’s not really about the food, but the food referencing,” the Northern California-based artist says in a phone interview. There is at least one glaring exception—an opulent performance last year at a private supper club in Santa Monica, but that, too, pointed to his elaboration of food as an index—in that case, of luxury. At its core, Reynolds’ practice explores food as a signifier of class and social status, a lever of aspiration; his work is steeped in the rituals and immersed in the politics and social meanings of food, how we consume it—both gastronomically and culturally—and how we use it to “manipulate, control and communicate.”

The Schauss Kitchen (2013–17), his most ambitious project to date, and Appetite Apparatus (2011), a related prelude to the encompassing Schauss Kitchen, explore appetite and denial. Reynolds produced a bevy of items for these projects entirely in a queasy Pepto-Bismol pink. They are both stand-alone sculptures and objects that are “implicated” in his performance—from the 1970s flip clock painted pink down to its rolodex-style split-flaps, to the pots and pans, cleaver and kitchen mallet, dish towels and food trays all in the same anti-acid pink. They appear as if they exude a tactile chalkiness that is reminiscent of the gritty texture of Kaopectate, as if, should you touch them, they might leave a light pink dusting on your fingertips.

“The Schauss Kitchen,” installation.

“I was obsessed with how food can manipulate, but also how color can manipulate,” Reynolds says. His research into the physiological effects of color led him to Schauss pink, better known as Baker-Miller pink—the description given by Dr. Alexander Schauss, the scientist who initiated a series of experiments in the late 1970s on colors’ effects on aggression. Schauss persuaded Baker and Miller, two naval officers at a correctional facility in Seattle, to paint the interior of a holding cell in the color he subsequently named after them. The studies demonstrated reduced aggression after 15 minutes of immersive exposure. In a later study overseen by Dr. Maria Simonson at The Johns Hopkins University Hospital, subjects also reported a suppressed appetite.

This rather unappetizing vision reached its zenith in Reynolds’ performance of The Schauss Kitchen two years ago at “Human Condition,” a sprawling exhibition in the former Los Angeles Metropolitan Medical Center in the West Adams district, where the work’s bewildering, alienating effect was compounded by the setting. All of the walls of the former Medical Center’s industrial kitchen were painted pink, and as he did in previous performances, Reynolds wore a matching pink suit and tie, Chuck Taylors, and rose colored glasses, and carried a thick pink tome of “recipes.” Cover-to-cover—all 800 pages—pink.

Christopher Reynolds performing in “The Schauss Kitchen” series, 2013–17.

The 1970s vintage flip clock—a thrift-store find—“was actually broken on 15 minutes, which was weirdly serendipitous—it flips, literally, every 15 minutes,” he says. A company in Burbank formulated the spray paint to turn it Baker-Miller pink.

He bought the glasses from one of the many online color therapy vendors offering Baker-Miller pink glasses.

There’s an aspect of coercive manipulation that echoes the initial study’s setting in a correctional facility. In his performances—for a private event at the Marine Art Salon in Venice, a public performance at Grand Central Market downtown, and a Yelp event for influencers—Reynolds adopts a “stone-faced” persona. Wearing the Baker-Miller glasses and staring at his audience, he walks around and “reads” from the Cookbook—the 800-page Baker-Miller-pink tome. “The more you read it, the less hungry you’re going to be.”

Cookbook, 2013, Baker-Miller Pink printed book (800 pages), edition of 3.

“I need to be implicated in the process. So I’m not only performing for the public, but I’m performing on myself,” he says. It’s a “play on performance anxiety and the fact that these [glasses] are lowering my blood pressure and calming me down.” But ultimately, there’s no satisfaction. Cooking show videos tantalize in the background.

As if to illustrate the nexus of unconscious desires and conscious self-manipulation, some time after the performance, Kendall Jenner blogged about painting a wall in her house Baker-Miller pink. Friends of hers had just been to “Human Condition” and told her over dinner of the color’s correlation with calming and appetite suppression. “Somehow my project is making her lose weight,” Reynolds sighs, “makes me sick to my stomach, but also kind of amazing.”

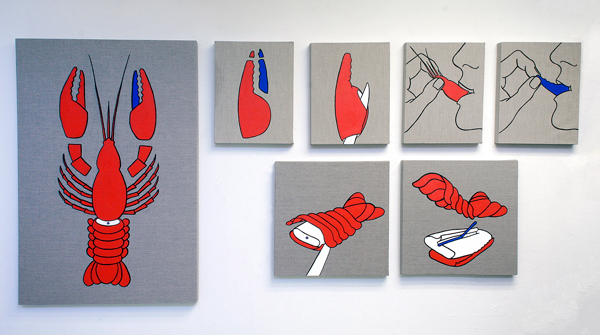

Reynolds’ fascination with food as an index of class mobility came sharply into focus in a gourmet event he produced in 2017—one of the few pieces he’s done with actual food—for the private Santa Monica supper club Stage and Table. The Claw and Cracker Club (2017) grew out of How to Eat Lobster (2011), a smaller-scale project that explores the ritual aspects of consuming.

How to Eat Lobster, 2011, (production still), video.

“I was obsessed with the lobster because it is one of the few remaining foods that we select ourselves. We pick it out. We kill it—I’m not saying in a barbaric way. There’s a very specific, ritualistic way that we disassemble and consume it. There’s a protocol,” he says.

Ritual was very much a part of the Reynolds family holiday celebrations, which included a Puerto Nuevo–style lobster dinner ever since the artist’s childhood. The family frequently visited Puerto Nuevo in Baja California, where meals also had a pronounced sense of ritual, Reynolds says—the parade of servers showcasing lobsters of various sizes, the act of picking out individual lobsters, which he found “fascinating and disturbing.” And How to Eat Lobster incorporated some of those ritual aspects. “It involved paintings and silk robes, in a play on religion meets fraternity meets secret society,” he says.

How to Eat Lobster (Blue Claw), 2011, installation detail

Lobster Bib (Blue), from “The Claw and Cracker Club” series, 2011.

Photo courtesy Sean Flaherty and Christopher Reynolds.