Your cart is currently empty!

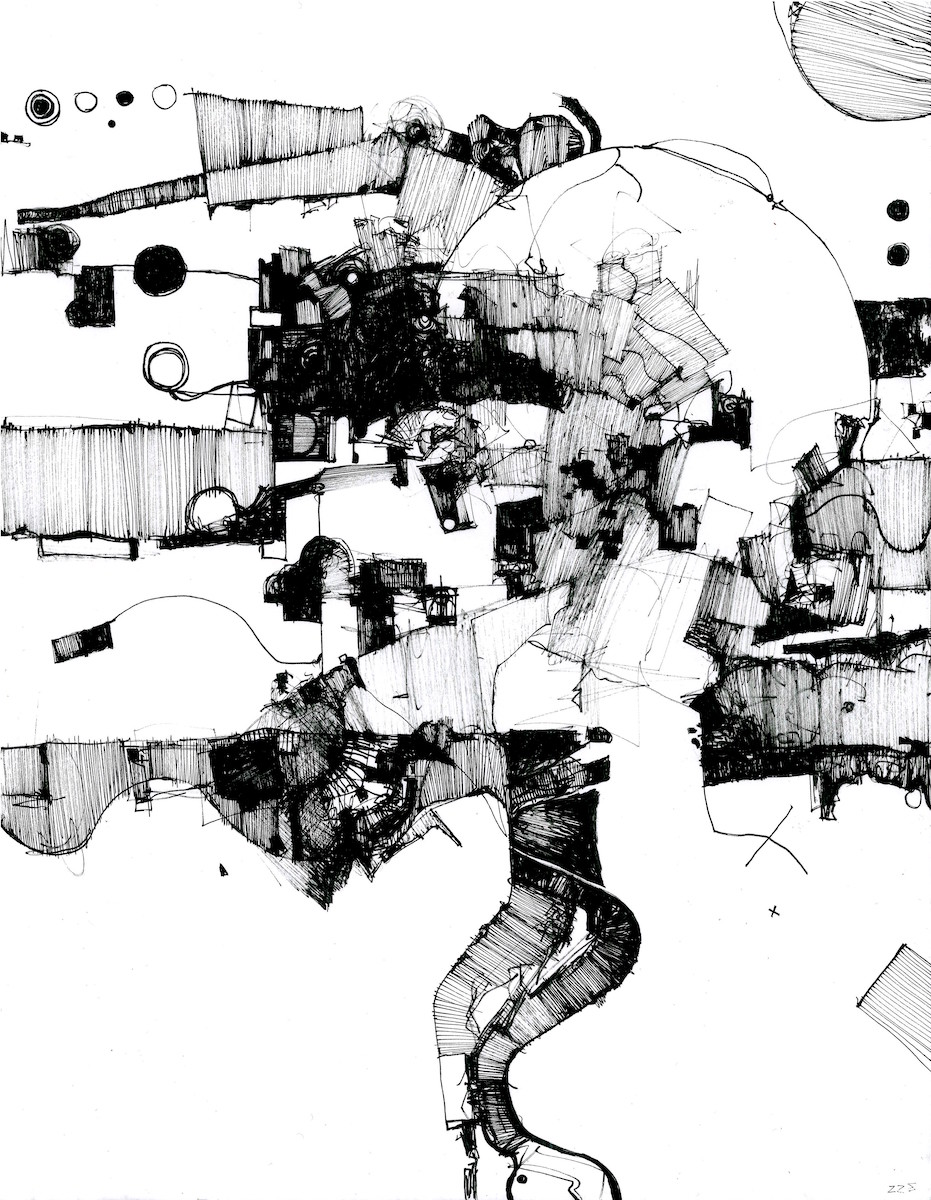

Prayer Against Turbulence Decoder

You know when an airplane goes from just rattling back and forth to when it feels like the engines stopped and you drop, like, 20, 50, who knows how many feet and then picks up rattling again? I hate that. I don’t want to die.

The nice thing about turbulence is it usually happens way after take-off and way before landing, so your tray tables do not have to be in the upright and locked position. Which makes it easier to draw.

I don’t know anymore how many times I’ve done this. I hold it together through bad weather that feels like it’s trying to kill me by taking a pen and drawing a thing. Wait, no, that’s inaccurate—it’s never a thing, it’s always some ragged half-made sketchy shape. The resulting drawing will inevitably be: spidery, black-and-white, unnameable, fragmented, not describable. It won’t be the most popular thing I make, but it will be real. It’s a prayer is what it is. I don’t want to die, I am going to make something so I don’t think about death. I draw until the rattling stops.

With this kind of drawing, you don’t plan. You don’t do what you are taught to do in art school: lay out every idea you’ve ever had and every tool you can master or imagine using, and curate from there some way of saying something about something.

This is the opposite kind of work: you start in a small arbitrary place on the paper and give yourself a small task: fill this in black. Left and right and left and right with the pigma .005 until just filling it in black doesn’t seem right any more, and then just move on intuition. Start not with an overview like a grand master at a chessboard, but start like a man in a tunnel, seeing by matchlight. Start with just one thing—anything—you know is real, like the left-right that makes the box black. And then look as close to you as you can for the next thing, and the next thing—just do the next thing you can do. And pray the plane stops moving.

It would be an exaggeration to say this is art that’s getting made because it has to, but it is art being made in the classic devotional mode, like Virgin Marys and wooden idols of fire gods: If I just do this, we will all get through. The crops will grow, the plague will end, 280,000 lbs of thrust pouring from the Pratt and Whitney will continue to overcome 577 tonnes sacrificed to the gods of mass and motion.

I don’t believe a word of it, and I can’t think of anything else to do.

Making a little black line is not a good idea. Making it thicker and thicker by turns is not a good idea. Making a picture because you’re worried you might die is not a good idea. It’s even worse because I definitely am not going to die in a plane crash—this rattling and drop-down broken coaster feeling is so common and survivable I can make it the lede for this piece and all of you recognize it and you only recognize that you recognize it because you’re still alive—because a bumpy flight is very easy to survive.

I’ve done so many of these drawings, though. I could find all of them, every bad flight for how many years, put them together on a white wall. You might not know this fear, but you know fear. You’re afraid of something—so you could see the lines of fear knowingly. You would know they are real and something human, and emanating from a human consciousness outside yourself. You couldn’t say very much constructive had been accomplished—you couldn’t say fear had been defeated or prevented or even that we’d learned much about fear—but in some small way some part of fear had become something else. Something you could look at, take in, and then live in, as part of your mental furniture. This other life feels fear as I do, as deeply, as undeniably. We are connected.

That’s all we ever do. Find a small thing that is definitely real and bang on it and bang on it again until it is not just what it is.