When Pouya Afshar was a young boy in Tehran, his grandfather gave him a gun and told him to kill the crow that was eating the fruit off the trees in the garden. The young boy did as he was told. Later his grandfather told him the crow might have been a mother feeding her young. Horrified at his own murderous deed, Afshar has never been able to erase that crow from his mind, nor any of the other visions of violence, destruction and oppression to which he was exposed while growing up in Iran during the 1980s and ’90s.

Instead, he uses his pen to transfer memories onto paper in boldly honest drawings that reanimate some of the horrors inflicted upon his country. Ayatollah Khomeini, Saddam Hussein and Ariel Sharon, as well as Chile’s dictator Augusto Pinochet and Bosnia’s murderous Radovan Karad‑ic are among the leaders brutally lampooned in his recent exhibition “Romance with the Crow I Killed.” Detailed with the recurring motifs of loaded guns, erect penises, accusing fingers and germ-transmitting mosquitoes (and combinations of these), Afshar’s witty pen-and-ink portraits render these political figures as violent, thuggish brutes driven by base male urges that create a culture of war.

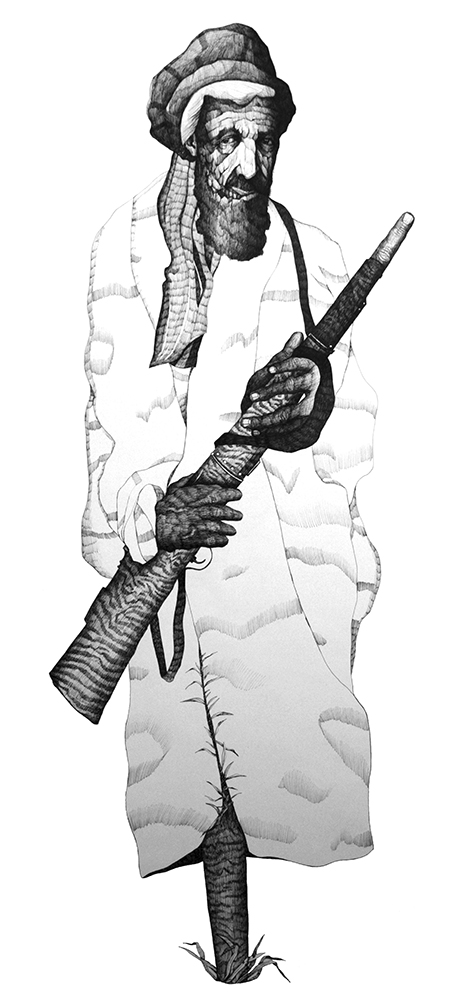

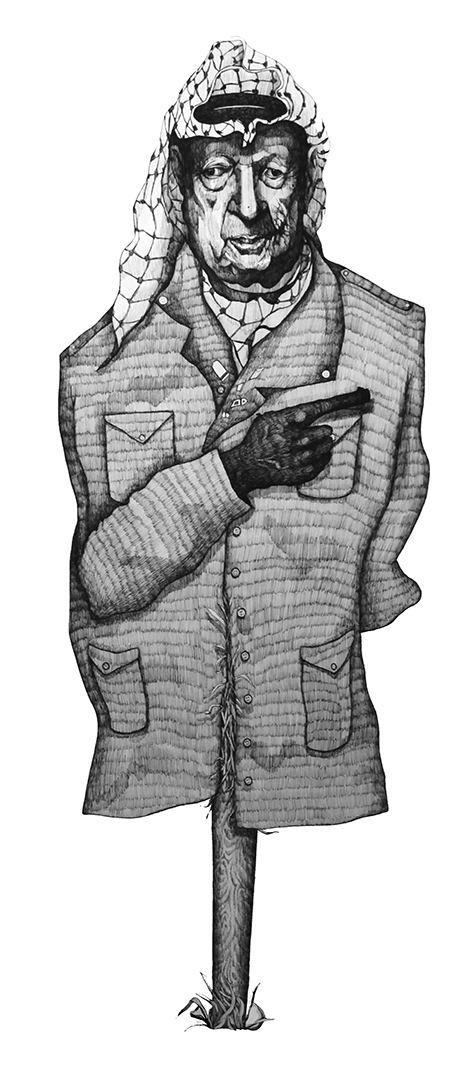

Afshar’s dry humor and meticulous draftsmanship are perhaps best displayed in his powerful scarecrow series, in which Middle Eastern leaders are depicted as busts on wooden posts, legless but still menacing. Using artistic wizardry, Afshar has merged the faces of two opposing leaders in each figure to create composite characters. The former Shah, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, is blended with his rival Mohammad Mossadeh, and Yasser Arafat and Ariel Sharon share a single face, suggesting that despite political divergences, these men were essentially cut from the same mold. In one drawing, a scarecrow’s hand is rendered as a handgun, pointed accusingly elsewhere. We see the gun motif replacing limbs explored in his sculpture Bucks (2014), in which rifle-legs inextricably link men with violence.

Afshar’s cinematic training enables him to take such images and combine them into larger narratives replete with meticulous details from his own life and events happening around him. In one panorama, The War (2014), which depicts the Iran-Iraq war, looping strands of barbed wire tie together images of Khomeini—his arms raised in a Hitleresque salute, an eyeless Saddam Hussein, fighter planes, guns, tanks, and women holding their dead children. A sinister mosquito with a penis-shaped body and a gun shaped like a horse’s head evoke the grotesque black-and-white portrayals of war and violence in Picasso’s Guernica or Kollwitz’s drawings and prints. By pouring these images onto paper in a dreamlike but stark montage, Afshar documents for us the suffering of the people in his home country, while also battling his own dark memories. Almost cowering in a corner is a cartoon character from Afhsar’s childhood. To the right, a dark and haunting crow reminds us of Afhsar’s first encounter with death and killing and the end of his own innocence.