It is probably safe to say that cartography evolved directly alongside oral and written narrative. Similarly, it is plausible to assume that fictional narrative began to take form as travel between known or proximate locations gave way to voyages across unplotted or unnavigated terrain—terra incognita—giving shape to experience, or simply dreaming up an alternate actuality to be fleshed out in the imagination. Long before Homer was composing the Illiad and the Odyssey, the dominant narrative was undoubtedly the tale of the voyage to a distant or unknown place.

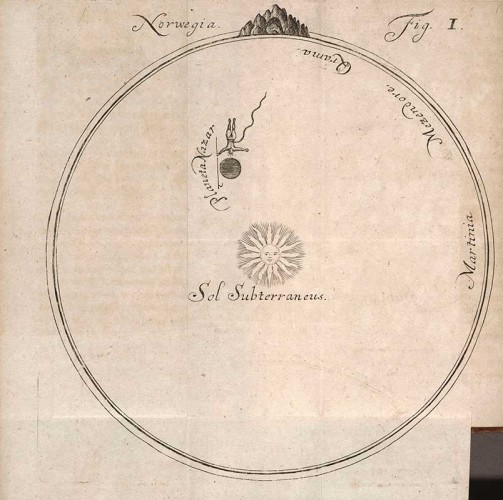

Ludvig Holberg, Map of journey to the center of the earth – “Nicolai Klimii iter svbterranevm” (printed book, 1741)

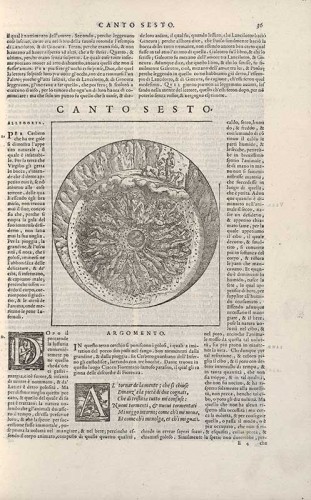

There was a long ‘pause’ between the maps of classical antiquity (Ptolemy—who coined the term, terra incognita—put his stamp on one of the more authoritative renditions), and the first maps to appear as the Dark Ages waned and the so-called ‘Age of Discovery’ dawned. At the time Dante composed The Divine Comedy (La Divina Commedia), the civilized world (such as it was) was largely dependent upon what had been mapped of the Silk Road across Eurasia and relatively crude nautical maps. The Divine Comedy is itself a kind of cosmography, albeit one mapping a still more speculative terrain between earth, hell and the ‘celestial kingdom’ of heaven. The first real novels took shape as much out of letters as journals, but it is probably more than coincidental that they parallel the 17th and 18th century golden age of Dutch mapmaking.

Dante Alighieri. Map of Hell from Dante con lespositione di Christofo Landino et di Alessandro vellvetello sopra la sua Comedia dell’ Inferno, del Purgatorio, & del Paradiso, 1564

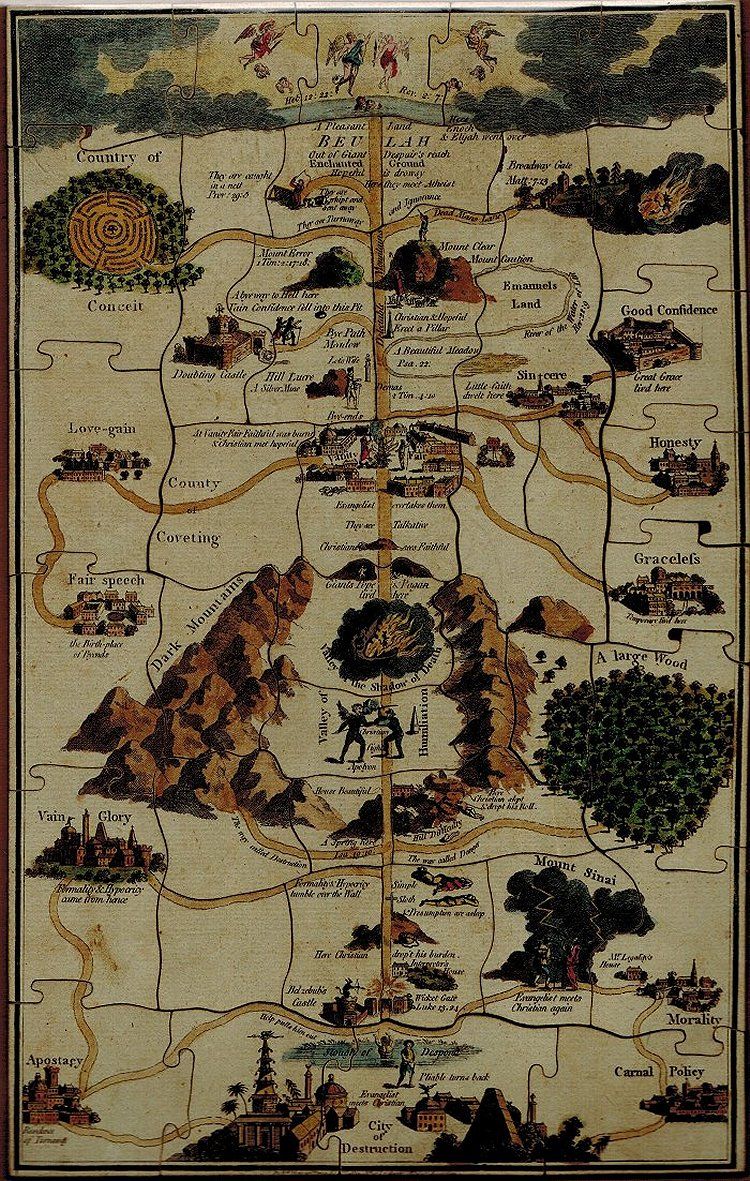

As the novel evolved and fictional voyages once intended mostly as satire (e.g., Defoe, Swift) gave way to tales of adventure, writers or their publishers began to essay their own maps; and in due course, maps were not only described or referenced but actually included in various print editions. But the fantastical paved the way for the more realistically terrestrial specimens. Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels included maps of Lilliput, Brobdingnag and his other fantastical islands—and The Huntington Library’s collection includes what must be one of its earliest editions. Other remarkable early editions with maps include John Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress and Cervantes’ Don Quixote, as well as a late 18th century edition of an annotated—and mapped—Divine Comedy.

John Bunyan, Pilgrim’s Progress

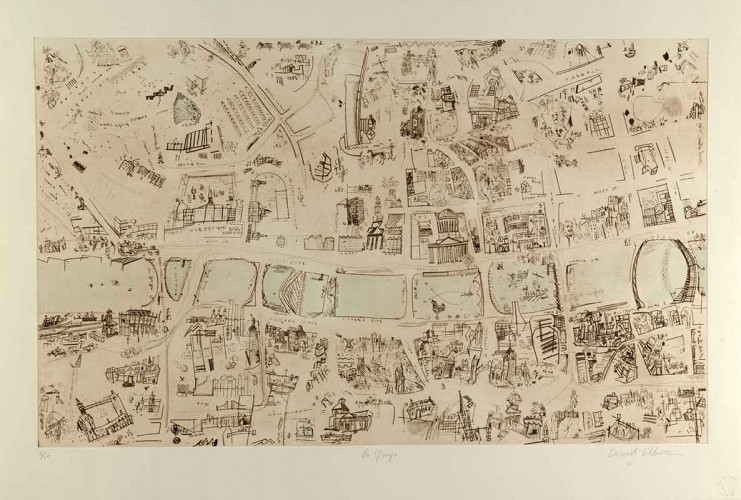

Out of this variegated and fantastical ‘terrain’, The Huntington has assembled an exhibition celebrating its rich holdings in such ‘mapped’ editions and more particularly the publication anniversary of a landmark 20th century literary masterpiece, which, notwithstanding its lack of an actual map, traces the micro-‘odyssey’ of its principal characters—Leopold Bloom most prominently—through 1904 Dublin, with almost cartographic precision—namely, James Joyce’s Ulysses. The result is Mapping Fiction, which examines the fascinating correspondences and frequently over-lapping dialogue between fiction-writing and map-making.

Anyone who has ever stopped at a hotel with a coffee/giftshop in this country or almost any other is familiar with the souvenir map with its over-sized neighborhood grids of city streets inset with miniatures of the city’s major landmarks, monuments, cultural institutions, and prominent retail, sports and entertainment venues. Art and architecture—and more specifically antiquity—probably had more to do with the evolution of this particular memento than literature. The Dutch weren’t the only Europeans venturing towards points south and elsewhere. This was also the period when the English and Germans re-discovered Italy; and what came to be known as ‘the Grand Tour’ became a rite of passage for children of the aristocracy and the prosperous merchant class. (It could be said that Cook’s Tours picked up for the masses where the first ‘grand tour’ guides left off—and one of their early 20th century travel guides with maps is included here.)

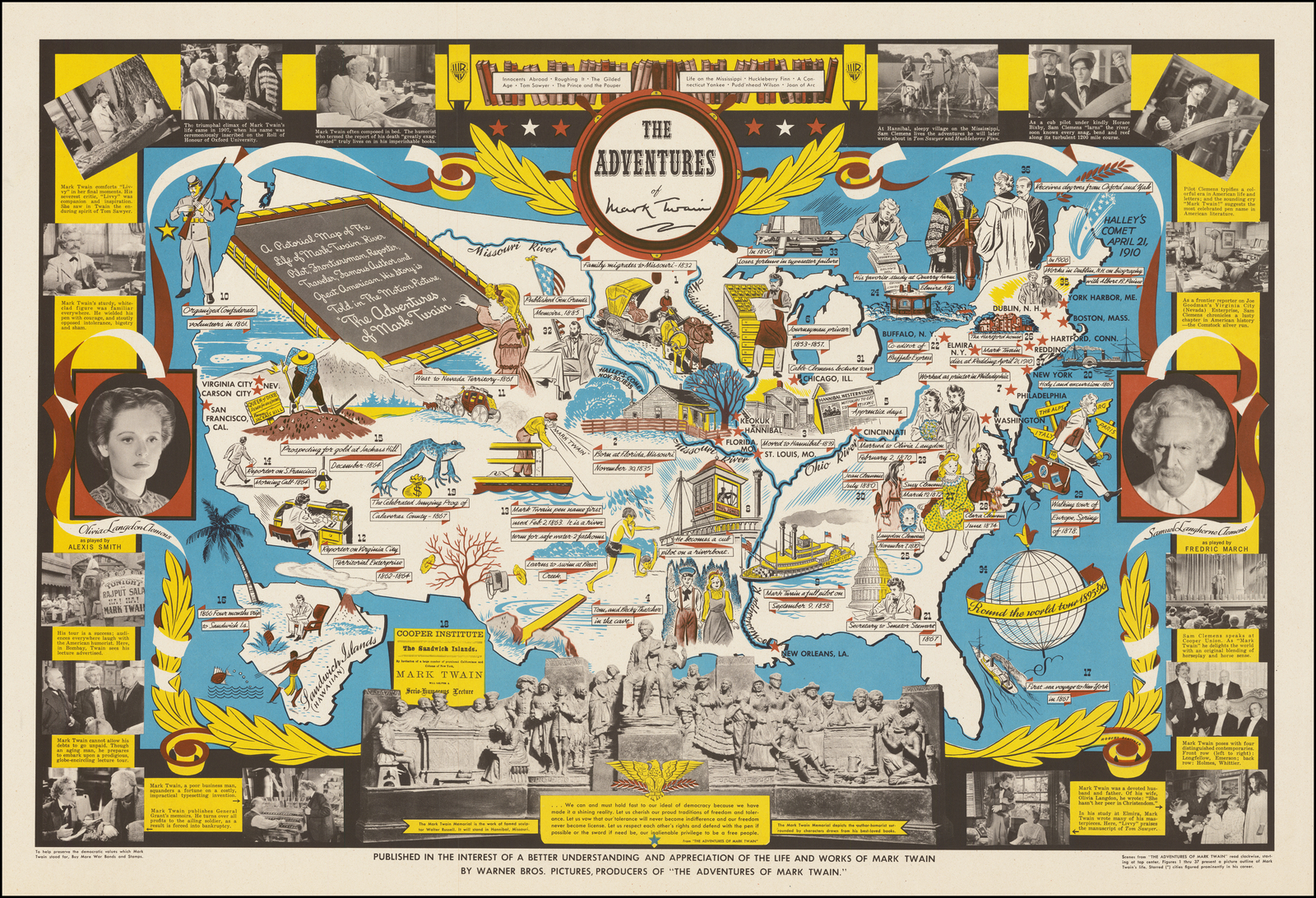

It didn’t take long for literary tourism to catch up with the ‘grand tour’, writers being among the first and most avid of those making such tours, a pattern which only accelerated as the 18th century gave way to romantic and realist novelists and poets of the 19th. The fashion crossed the Atlantic in due course; and not five years after the Civil War, Mark Twain, whose earliest stories and books were themselves a species of travel and adventure journalism, published a collection of his dispatches from Europe and the Middle East for the Alta California and other newspapers, Innocents Abroad, that in effect was a sharply satiric and distinctly American send-up of the grand tour.

Although the early editions of Innocents Abroad were abundantly illustrated, none of Twain’s subsequent memoirs and collected travel writings (e.g., Life On the Mississippi and Roughing It) included maps—ironic for a writer who took his pen name from a navigation term he picked up as a Mississippi River steamboat pilot and whose life was itself the grandest of tours. Curator Karla Nielsen offers the consolation of a Warner Bros. promotional map for its 1944 film, The Adventures of Mark Twain, which although confined to the continental United States, faithfully reflects that adventurous spirit.

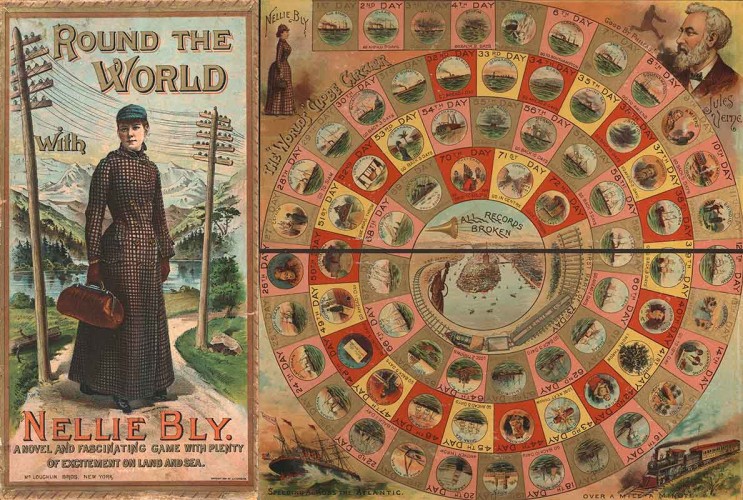

Adventure in fiction inevitably begat adventure in real life. Jules Verne’s Around the World in Eighty Days inspired the New York World to send the intrepid Nellie Bly around the world in 72. What could go wrong—or right? Readers were invited to speculate—and give it a dry run by way of a board game inspired by the journey. Although maps continued to find their way into travel and adventure literature both factual and fictional (Robert Louis Stevenson’s map for Treasure Island is here), still more great novelists plotted their fictions across land masses far closer to home, whether the cities and villages of England and France (e.g., Woolf’s Mrs. Dalloway; Hardy’s The Mayor of Casterbridge), or even rural counties of the American South (Faulkner’s sketch for the fictional Yoknapatawpha County—based loosely on his native Lafayette County, Mississippi and the setting for 16 of his novels—for Absalom, Absalom! is also here).

But by far one of the greatest literary ‘mappings’ is Joyce’s Ulysses. All but pre-ordained in Joyce’s preceding books, from Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man to Dubliners, it swallows the city of Dublin whole; and in few books does the city seem as engraved into the bodily flesh of its characters—and certainly its author’s. The great irony is that Dublin rejected its great genius with a ferocity that might be described as (to borrow from U.S. District Court Judge John Woolsey’s decision overturning the U.S. Customs Office’s designation of the book as obscene and legalizing its publication in the United States) ‘emetic’; the book was written over seven years far from the place of its germination between Zurich, Trieste and Paris. (Needless to say, the first Shakespeare and Co. edition of the novel, which was finally published in Paris, is here.)

David Lilburn, “In media res” (2004) – “The Quays,” drypoint etching with ink and watercolour

Like the book’s original U.K. and U.S. customs obscenity designations, this could not stand; and in 2004, Ireland’s Office of Public Works commissioned artist David Lilburn to produce a series of etchings integrating the characters’ trajectories and the novel’s episodic structure within the varied topographies and landmarks of the city’s plan for the 2004 exhibition James Joyce and “Ulysses” at Ireland’s National Library in Dublin. Lilburn’s magnificent suite of seven drypoint etchings, In media res, is without a doubt the crown jewel of the exhibition—the ultimate ‘souvenir maps’ for a literary tour of Dublin. Phoenix Park references a historic political murder that figures in the novel’s background mused upon by both Stephen and Bloom; The Quays, the Ormond Hotel bar and neighborhoods around the hotel and the bar’s backroom “saloon” (and where Bloom buys his wife, Molly a copy of The Sweets of Sin); O’Connell Street, Dublin’s central thoroughfare anchored by historical monuments, the City Hall and Dublin Castle; Loop Bridge, with still more landmarks, as well as Sweny’s chemists and Holles Street Maternity Hospital, where Stephen drinks with medical students and Bloom checks in on a maternity patient; Eccles Street, where Bloom and Molly live (at No. 7); Coastline is more or less where the novel begins; and Howth, Molly’s ‘past recaptured’ moment, as she recalls (from her bedroom on Eccles Street) her orgasmic ‘Yes’ to Bloom’s marriage proposal at Howth Head at the north side of Dublin Bay.

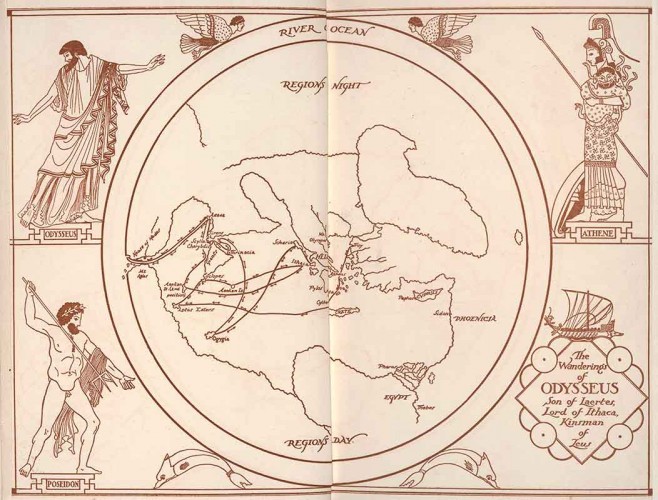

A 1935 edition of T. E. Lawrence’s (yes—that Lawrence) translation of Homer’s Odyssey—with Lawrence’s map tracing a vaguely Aegean geography with an assurance neither Odysseus nor Homer and his sources could have claimed—becomes a fitting pendant to this compact yet fantastically expansive exhibition. This is the sort of show that inspires both deep dives into libraries and intense wanderlust. I have no doubt Raymond Chandler and Ross Macdonald have inspired literary tours of Los Angeles; but closer to The Huntington, Lynell George has mapped out walking and bus tours tracing Octavia E. Butler’s typical walks and transit routes between Pasadena and downtown Los Angeles. I highly recommend following the viewing with a literary tour of The Huntington’s Chinese Garden, which the curators have also thoughtfully mapped out.

A 1935 edition of T. E. Lawrence’s (yes—that Lawrence) translation of Homer’s Odyssey—with Lawrence’s map tracing a vaguely Aegean geography with an assurance neither Odysseus nor Homer and his sources could have claimed—becomes a fitting pendant to this compact yet fantastically expansive exhibition. This is the sort of show that inspires both deep dives into libraries and intense wanderlust. I have no doubt Raymond Chandler and Ross Macdonald have inspired literary tours of Los Angeles; but closer to The Huntington, Lynell George has mapped out walking and bus tours tracing Octavia E. Butler’s typical walks and transit routes between Pasadena and downtown Los Angeles. I highly recommend following the viewing with a literary tour of The Huntington’s Chinese Garden, which the curators have also thoughtfully mapped out.

Mapping Fiction — through May 2, 2022 — in the Library’s West Hall — The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens