As we move forward into 2018, we recognize a bit more concretely how our experiences in 2017 and immediately prior influenced and began to reshape our perception of the larger (and certainly the political) world. This is nothing new. Radical cultural change (or its culmination) will do that – whether it be a technological watershed (or its cumulative impact), economic depression or radical austerity, radical and institutionally reinforced inequality, ascendant fascism (which frequently accompanies these phenomena hand-in-glove), or rampant institutional corruption or subversion. So it’s not surprising that many of us find ourselves reexamining the way we perceive and look at the world on every level. One aspect of my own ‘take-away’ from the year was that artists and audiences alike were beginning yet again to deconstruct their ways of seeing, knowing (and being) and recomposing their views and perspectives of objects and their placement in the world.

One of the most notable shows of last year that placed this deconstruction front and center – open through February 4th, at LACMA – is Sarah Charlesworth: Doubleworld. Charlesworth’s work was aligned closely (and appropriately) during her lifetime with Pictures generation artists, but, setting to one side her deep immersion in photography, her overall artistic foundation was more broadly Conceptual and theoretically driven. (Two of her early mentors were Douglas Huebler and Joseph Kosuth.) Through many different series, executed between the early 1980s and her death in 2013, her meticulously executed and polished constructions of images (variously photographed, appropriated, and/or rephotographed or composited, staged or ‘directed’) probe a ground-zero phenomenology of image and image-making.

There’s a tendency in the peculiarly tweaked (and constantly morphing – it may be something else soon enough) argot of political punditry and corporate flackery to speak of the ‘optics’ of a given situation – referring not to the physical properties of visible light or visual sense or the instruments we use to explore or utilize them, but to the presumed impression or perception we may take from a particular situation or set of circumstances.

Charlesworth was already thinking about the way we take apart such ‘optics’ – and their accompanying conventions, clichés and stereotypes – in one of her earliest shows. In the essay she wrote for the 1982 show, In-Photography at CEPA Gallery in Buffalo, she wrote, “Did the camera take that picture? Did the picture impress its image by convention upon the eye of the unsuspecting photographer? Or did a person create the infinite perfect just-so-ness of the world that arranges itself before its avid lens?”

Charlesworth is clearly interested in the ‘just-so’ configuration and what fastens eyes and mind to it in lockstep. She’s interested in the way we inscribe and magnify the primary subject/object with importance or significance, the way impressions of varying depth or superficiality are reconstituted and elaborated – through rite and ritual, certainly through mass-media, through imaginative re-telling, or through sheer desire. She was deconstructing the internal micro- and macrocosmic narratives, the ‘story’ elements driving such image-making; also the subjective aspects of such moments, their cultural and psychological preconditions.

Exploiting a variety of techniques and tactics, and frequently combining and cross-cutting or hybridizing among them, Charlesworth is constantly taking these elements apart throughout her career. Throughout, there’s a kind of freezing and fracturing of the visual grammar and syntax to a degree approaching crystallography. For Charlesworth, the way we see is inextricably bound up with picture-making; and, conversely – setting aside physical optics – picture-making is fundamental to the way we see. In the course of her investigations, she takes the notion of picture-making – and the picture itself – to both a ground-zero of picture-object and a kind of chambre-claire of image-making (or, as Roland Barthes’ translator would render it, Camera Lucida – a critical text Charlesworth reviewed for publication and which would have enduring resonance for her).

In the aforementioned In-Photography essay, Charlesworth sketches out what might be a defining statement of intent for her entire career: “Sometimes I open an image in order to make room for myself, to disrupt the closure of an intensified known. The entry into an image, the rupture and reintegration of its coherent form, exposes that which lies between meaning, the reciprocal meeting of an object and its apprehension.” Charlesworth was already exploring those ruptures and reintegrations in her earliest work. The photostatted paste-up works of her Modern History series (1977-79) were already ‘sampling’ from the rhythm, pulse – and encoded cultural politics – of the collective narrative and mythologies propagated in mass media, specifically newspaper front pages (still almost iconically important in the late 1970s and early 1980s). They’re still fascinating to look at; and for those of us who still look at newspaper front pages in the mornings, everything about the configuration of photos and print columns (to say nothing of their placement above and below ‘the fold’) remains meaningful.

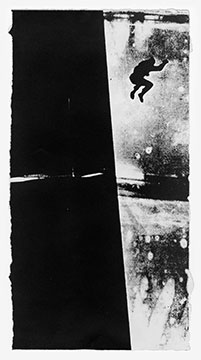

Almost all of the images appropriated for Charlesworth’s Stills series are taken from newspaper or newswire/media sources, and here Charlesworth begins to open, to enter the image in earnest. The strategy in cinematic terms is a kind of simultaneous zoom, freeze-frame, and dissolve. All of the images dwell in paradox – really a kind of void – where the picture (by way of the photographer, or more precisely the artist here) frames the meaning. The subject matter is grim: figures falling or leaping from windows and buildings, presumably to their deaths (although one is presumably taken from a movie stunt), escaping fires or committing suicide. Charlesworth has both deliberately cropped the photographs (sometimes artfully suggesting an actual ‘tear’ from the sourced newspaper) and blown them up to human scale. They’re no longer images we can hold in our hands or even open up on a table. In enlarging the scale, Charlesworth has both expanded the moment and immersed both subject and viewer in it. The cropping in the meantime, reconfigures the frame, detaches the subject from its surround, and alters (if only by degrees) its context. The fall becomes a suspension in a space redefined as both isolation and immersion, even as we remain aware of the cruel ironies beyond the frame.

But Charlesworth is already probing (and conceivably suffering) ironies and obsessions well beyond this particular frame – the kind of obsession that, as Douglas Crimp wrote about it for his breakthrough 1977 Pictures show, “is the very nature of our relationship to pictures.” Charlesworth is intent upon cutting through the half-tone of commercial and mass-media images and imagery, to see through those voids. She’s already experimenting with the notion of reading one image through another in her Red Collages, welding Barthes’ dicta from Lucida of a ‘wounding’ with the requisite sly cultural commentary. Her Rider (1983-84) with its fragment of a glamourous Natalie Wood reaching (yet cut off) through a silhouetted cowboy on a rearing horse is a cool but throbbing vibrato of yearning, a kind of psycho-graphic frisson deployed with rhetorical precision.

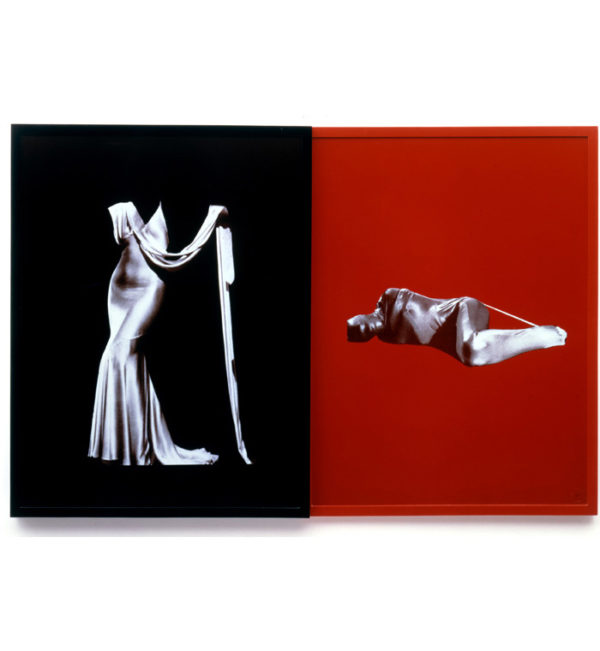

Charlesworth is always acutely conscious of the reversals at play in almost any conventional photographic treatment of its subjects. The larger concern veering into Charlesworth’s focus here is the orchestration of desire. She detaches and isolates her displaced silhouettes still more decisively in the Objects of Desire she constructed between 1983 and 1989, investing them with greater importance and singularity. Frames are defined yet merged (chromatically) with the monochrome fields, frequently (though not always) bright red. The object as gesture, as symbol is the singular focus; and Charlesworth is fairly straightforward about what she’s getting at, whether the ‘objects’ are presented singly, as pairs or diptychs (in one instance a triptych), or arrays. The paired vertical and horizontal of Figures – with its gorgeously body-contoured 1930s-style evening dress facing off a recumbent bondage figure (that could be male or female) read as an inevitable (or perhaps just irresistible) follow-up to Rider’s love- with-the-proper-phantom-cowboy. Elsewhere in the series, the images have an ideogrammatic quality: the confection of Blonde (1983-84) hairdo in its black field; the bondage Harnesss (1983-84) in its red one; the geisha peering through a teardrop tear in another red field. Charlesworth probes and plumbs with variable delicacy and boldness the gulf between what is seen and what is signified. The balance is not always quite so fraught. As the series evolves, Charlesworth’s pairings suggest a point of equilibrium and equanimity if not exactly transcendence.

Charlesworth is always acutely conscious of the reversals at play in almost any conventional photographic treatment of its subjects. The larger concern veering into Charlesworth’s focus here is the orchestration of desire. She detaches and isolates her displaced silhouettes still more decisively in the Objects of Desire she constructed between 1983 and 1989, investing them with greater importance and singularity. Frames are defined yet merged (chromatically) with the monochrome fields, frequently (though not always) bright red. The object as gesture, as symbol is the singular focus; and Charlesworth is fairly straightforward about what she’s getting at, whether the ‘objects’ are presented singly, as pairs or diptychs (in one instance a triptych), or arrays. The paired vertical and horizontal of Figures – with its gorgeously body-contoured 1930s-style evening dress facing off a recumbent bondage figure (that could be male or female) read as an inevitable (or perhaps just irresistible) follow-up to Rider’s love- with-the-proper-phantom-cowboy. Elsewhere in the series, the images have an ideogrammatic quality: the confection of Blonde (1983-84) hairdo in its black field; the bondage Harnesss (1983-84) in its red one; the geisha peering through a teardrop tear in another red field. Charlesworth probes and plumbs with variable delicacy and boldness the gulf between what is seen and what is signified. The balance is not always quite so fraught. As the series evolves, Charlesworth’s pairings suggest a point of equilibrium and equanimity if not exactly transcendence.

Charlesworth was always acutely aware of the parallel ‘doubleworlds’ she straddled in her work: the doubleworld of image and object and the doubleworld of image and imagery. This comes across inescapably through almost all of her work – but the elegant tondos she constructed in Natural Magic (1992-93) were a kind of climax of this counterpoint. She explored it with an almost archaeological degree of obsessiveness in Doubleworld (1995), in which her meticulously constructed and staged (and one actually titled) allegories are paired with vintage optical instrument (e.g., Voyeur (1995) with its telescope and suggestively parted curtain). Her 2000 0+1 series is almost a 180-degree reversal of Doubleworld’s extended allegories and natures mortes of picture-making and optics (and Empire Light’s explosion of light onto a twilit Empire State Building). Here, Charlesworth returns to her favorite motives as if her fundamental ‘elements of style’ were the only authentic means of testing her fundamental ‘ways of seeing’, setting a kind of level for the limits of apprehension; e.g., the Lakshmi and snakes from Objects of Desire, the book from Natural Magic – this time covered only in white light, the Buddha and bowl and column (this one with two capitals); and that trope of rationalist modernity, the grid (actually a ‘screen’). The contours of the objects are barely discernible. It’s as if the view we’re given is actually a squint. We’re either scarcely able to open our eyes to these objects, or blinded by the light. The only difference between the ‘Seated’ Buddha and the “Levitating’ one is the barest suggestion of shadow at the base.

In the last body of work she produced before her premature death in 2013, Available Light, she makes her studio and variously refractive and reflective objects in it her subject. In another kind of 0+1 approach, with the studio setting off the dimensions of an idealized chambre-claire, the ‘wound’ here is rendered here as purest symbol. Each subject opens up or offers a world – by lens, aperture, vessel or pure energy. I’m not quite sure I can find a trace of the Barthes we know she admired in either these images or the immediately preceding series (whether the Barthes of Camera Lucida or Le Degré zéro de l’écriture). But we can trace both an artistic or philosophical and even practical methodology in the images – locating, placing, and finally navigating the visual field, and grasping at our perceptions and what we can describe of them between the light and the shadow.