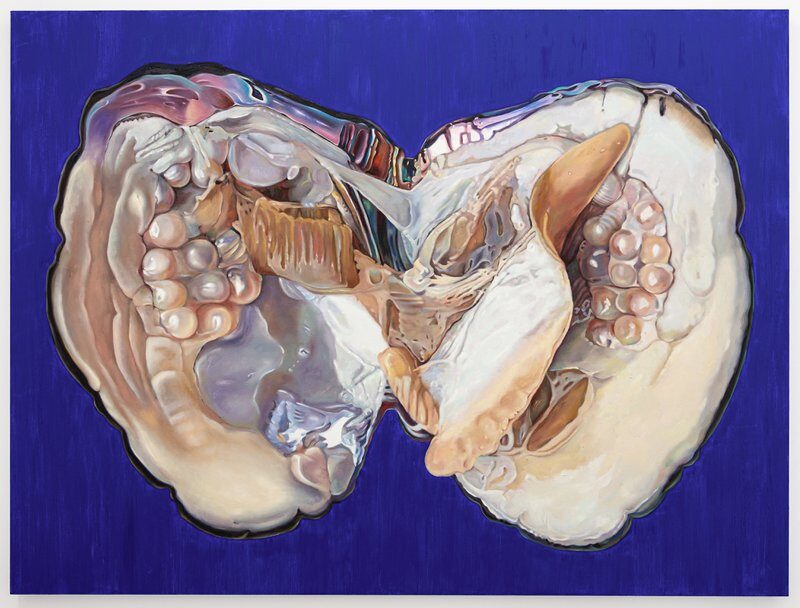

Fawn Rogers’ exhibition “Your Perfect Plastic Heart” at Wilding Cran Gallery presents a series of paintings depicting oysters and their gooey erotic membranes. At first glance, these works struck me as a cross between Marylin Minter and Chloe Wise–glittery hyperrealist paintings of gastronome with a hint of kitsch. Rogers takes the oyster as her subject to frame the story of our precarious reality as we navigate living and dying in the age of the Anthropocene (a term Rogers uses that I tend to shy away from).

As Rogers points out, oysters have been historically commodified as culinary delicacies–served with lemon and mignonette–and their pearls as a luxury material that signifies wealth and taste. Human fingers creep out of the oyster’s shells, tracing their slimy edges and protruding pearls, eroticizing and likening their forms to female anatomy. The oysters are decontextualized from their natural habitats and painted against nondescript color field backgrounds. As if to evoke an eco-Yves Klein fantasy, the painting titled Epoquetude is foregrounded by a vibrant cobalt blue, further stressing their condition as rarified commodities. I’m left wondering, how does Rogers’ sexualization of nature contribute to the ecofeminist conversation?

While the pearl industry certainly speaks to the story of human exceptionalism and exploitation of nature, another related, resurgent, and collaborative story lies beneath Rogers’ opalescent surfaces. Oyster farming is surprisingly sustainable; not only that, it significantly benefits the ecosystem as oysters are natural filtration systems that promote biodiversity. What is not sustainable is farming and shipping oysters from Maine to Los Angeles. Rogers claims that “the pearl’s inception hinges on corruption, manipulation, and desecration.” While this is true, oysters also contain histories of indigenous harvesting practices. Rogers’ paintings present pearls and mollusks from the vantage point of capitalist consumption to tell an aestheticized story of the Anthropocene. It’s hard to deny the alluring quality of Rogers’ paintings, but they seem to miss vital connections to a more resurgent ecofeminist story, lost in the painting’s erotic surfaces.

While I’m aligned with Rogers’ ecofeminist agenda, I do wonder if her painted critters tell the story of environmental urgency and disaster she aims to inform. Or are oysters just enticing to paint and sexy to look at? Ecofeminism’s strength and potential lie in its commitment to cultivating tentacular thinking, resurgent strategies, and multispecies kinship. As Donna Haraway likes to say, “It matters what thoughts think thoughts. It matters what knowledges know knowledges. It matters what relations relate relations. It matters what worlds world worlds. It matters what stories tell stories.” Rogers’ oyster story is one among many other related (hi)stories of conquest, resistance, and resurgence.

Wilding Cran Gallery

1700 S. Santa Fe Avenue, unit 460

Los Angeles, CA 90021

On view through June 25, 2022