“A national political campaign is better than the best circus ever heard of, with a mass baptism and a couple of hangings thrown in.” –H.L. Mencken

At no time in history is the character of a nation brought into more vivid relief than during elections. And no medium illuminates its current moral complexion – warts and all – with more affect and clarity than photography, the visual language of light and time itself, with the power to burn shared human experience into our collective conscious for the ages.

Capturing the essence of an election is no easy task. Photographers covering them frequently operate under the most constrained and chaotic circumstances. The best of them quickly recognize the moments worthy of sanctification, simultaneously configuring a complicated and ever shifting combination of technical elements (angle, focal length, film speed, shutter speed, lighting) to optimally translate their vision – all in a matter of seconds. And they must do so with a rare level of consistency.

But technical mastery is only the starting point for the eight superb visual poets and storytellers profiled in this article, all having won the highest honors in their field. They dive more deeply and passionately into their documentations, creating distinctive and influential bodies of work. Their style and aesthetic choices arouse emotions and illuminate the subject in a unique and memorable way. They make photographs that inspire, amuse and provoke, forcing us to rethink the human condition; in this case, to contemplate the nature of democracy, the electoral process, and our role in its history. Their work represents a cross section of the “originals” referred to in Alexis Tocqueville’s famous quote: “History is a gallery of pictures in which there are few originals and many copies.”

JEFF JACOBSON

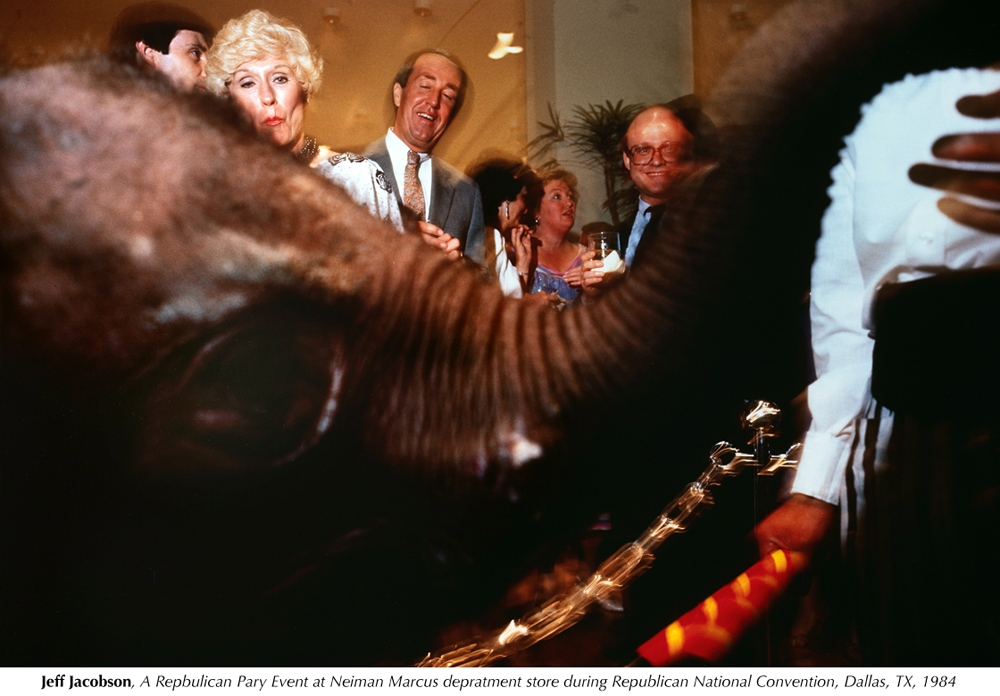

In 1984, a photograph was published in a mainstream news magazine of a Republican National Convention social gathering in full swing place at a Neiman Marcus department store in Texas. Filling the foreground of the frame is a real elephant, the curve of its trunk delineating an array of posh attendees reveling in detached amusement, as if the captive creature before them was just another decorative prop.

It was a signature Jeff Jacobson photo, part of a body of work that transformed the face of political photography. Not only for its ground breaking style, but also for its iconoclastic attitude.

In addition to being the first photographer to shoot the political scene in color slide film, Jacobson pioneered a carefully calibrated technique that combined long shutter speeds with blasts of strobe, spotlighting subjects hit with the flash while the ambient light pouring into the frame from the long exposures created impressionistic movement. Chaotic energy in the room was transformed into visible form, while fleeting fragments of gesture and facial expression were frozen in vibrant graphic detail. These playful multi-layered tableaus often captured otherwise unnoticed manifestations of the political world’s substratum – the fake smiles, greed, pretension and subtle insanity of it all – as well as the unintegrated ideologies percolating behind its “holier than thou” public image.

Influenced by the writings of Hunter S. Thompson and the drawings of Ralph Steadman, Jacobson’s work was their photographic counterpart. “I felt like I was doing Gonzo journalism,” he said. “That’s what I was seeing and feeling, the real underbelly of the political world and the ludicrousness of it.”

Growing up as a Jewish kid in lily-white Iowa during the Eisenhower McCarthy era, Jacobson always sensed there was “an alternative narrative not being told. ” His early interest in social justice later developed into a career as an ACLA lawyer, further tuning him into the political zeitgeist. But after taking a photography workshop in the mid ’70s with then Magnum Photos chief Charles Harbutt and experimenting with a camera at a 1975 George Wallace rally, he ditched his life as an attorney and began shooting presidential primaries on assignment for major magazines as early as 1976, continuing to do so well into the next decade. Jacobson clearly preferred photography to the law as a way to smoke out the “untold truths” that had bedeviled him since he was a boy.

The “elephant in the room” in Jacobson’s RNC picture took on more proverbial meaning in the journalistic sphere. His radical approach to shooting politics had begun deflating the prevailing myth that art and photojournalism are mutually exclusive, that there is some “official” objective reality that must be faithfully communicated without contamination from the shooter’s subjective feeling or point of view.

Jacobson’s images in fact brimmed with truth. His tailor-made technique simply revealed alternate layers and pieces of it in the objective world that his subconscious mind already sensed since childhood, and that the undeniably subjective passion he had for art and social justice animated.

“I’m in the never-never land between the art world and the photojournalism world,” said Jacobson, feeling pure objectivity was an illusion and the most successful pictures came out of “the intersection of the subconscious and reality.”

Jacobson recently passed away after a long battle with cancer. He had long since moved on from satirically bent political photography, focusing on books and teaching. His work became even more ambiguous and complex with age, more of it making its way into important museum collections. Facing mortality, he authored his third and final book, The Last Roll (Daylight, 2013), a highly personal project showcasing each carefully selected image he recorded with a precious last roll of his beloved Kodachrome 64 film that was being discontinued – the same film he had used exclusively in his campaign photography when everyone else was still shooting politics in black and white.

The outpouring of tributes after his death in August attested to the profound influence he had on both his students and peers.

“I think of Jeff Jacobson as a photographer’s photographer,” said Holly Hughes, longtime Editor-in-Chief of Photo District News. “What I mean is that his influence among fellow photographers has spread far more widely than his acclaim among critics might suggest. . . Many photographers working in the documentary tradition have had to reckon with the questions Jacobson’s work raised.”

Said Kenneth Dickerman, Photo Editor of The Washington Post, “Jacobson was a magician when it came to political photography. But his wizardry didn’t stop there; it touched everything he did. . . For me, his books My Fellow Americans and Melting Point stand as benchmarks in photography.”

DAVID BURNETT

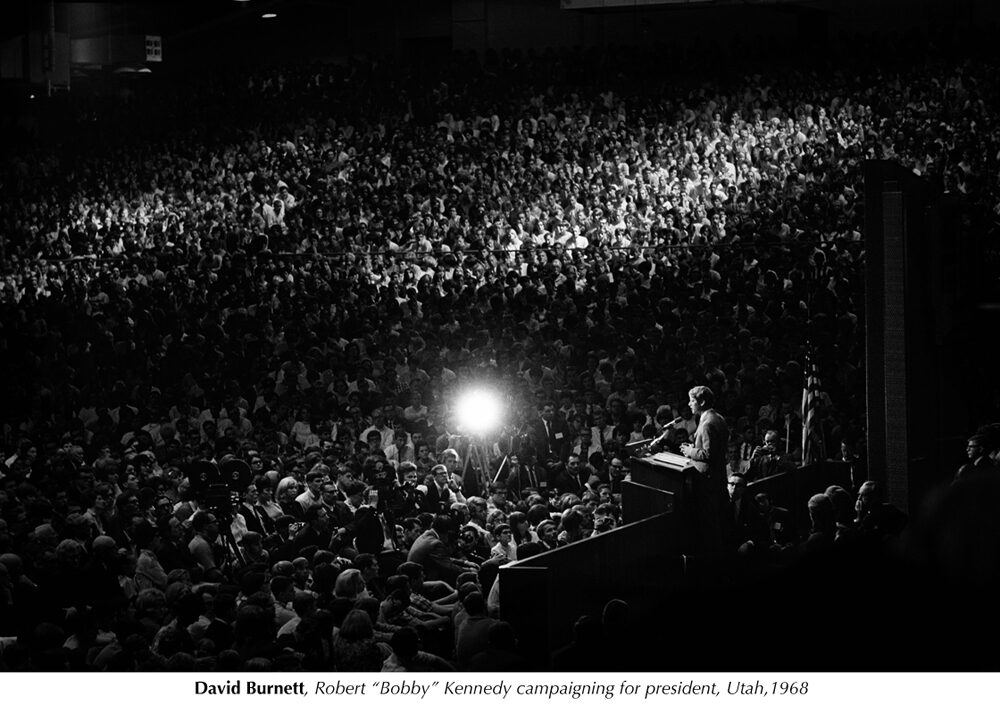

A journalist who has covered the world’s most important events spanning five decades, 60 countries, several wars and revolutions with a few Olympic Games thrown in, David Burnett, named one of the “100 Most Important People in Photography” by American Photo magazine, is also a veteran of the political scene in Washington, having photographed every American president from John F. Kennedy to Barack Obama.

Influenced by Douglas Duncan’s 1968 photos of Richard Nixon and mentor Raymond Depardon, Burnett’s election photography is a classic example of the traditional approach to political coverage. Exemplified by his black and white photo of Robert Kennedy speaking to a sea of citizens at 1968 Utah rally, its restrained subjectivity and stately composition frame a perfectly chosen moment in time, drawing the viewer in with its historical import and formal beauty.

Other legendary photojournalists with vast political portfolios working in the 20th century through the present day belong to this camp, such as David Hume Kennerly, Bill Eppridge and Pete Souza, to name a few. But after the century turned, Burnett took a stylistic detour, sparked by a fire sale purchase of a big old 4×5 Speed Graphic when the Salt Lake Tribune was clearing out their equipment closets. Wanting to try something new and avoid being assigned to the impending Iraq war, he headed to D.C. with his eccentric conspicuous apparatus and began pointing it at the political scene.

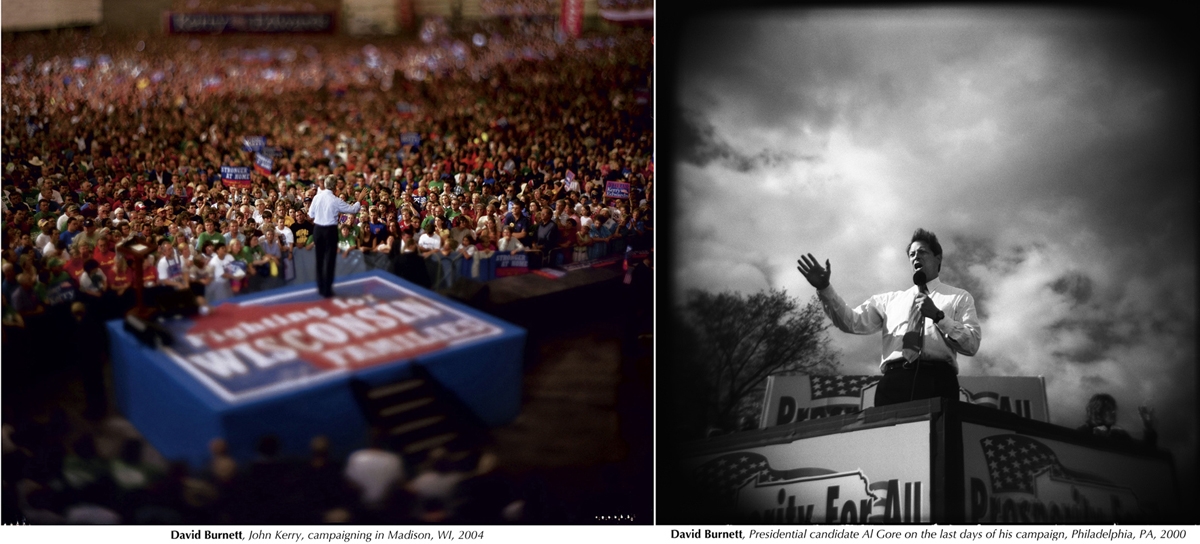

Rather than more true-to-life renderings produced by the 35mm cameras Burnett had been using for 30 years, the large-format bellowed contraption created more dreamy images redolent of 19th century photographs, its poetic effect illustrated in his 2004 color photo of John Kerry campaigning to a crowd in Wisconsin. He also experimented with the Holga, an even more primitive camera that yields random vignetting, blurs and light leaks. The throwback technique was already being revisited in fine art and fashion photography, but at the time no one had applied it to contemporary fast-paced elections.

Burnett’s retro modernist maneuver did not go unnoticed. Much to his surprise, the work was published repeatedly in top mainstream news magazines – perhaps a reaction against the deluge of the cold synthetic images the early digital era of photography had recently unleashed – further expanding notions of how important political events like 21st century presidential campaigns could and should be rendered by photojournalists.

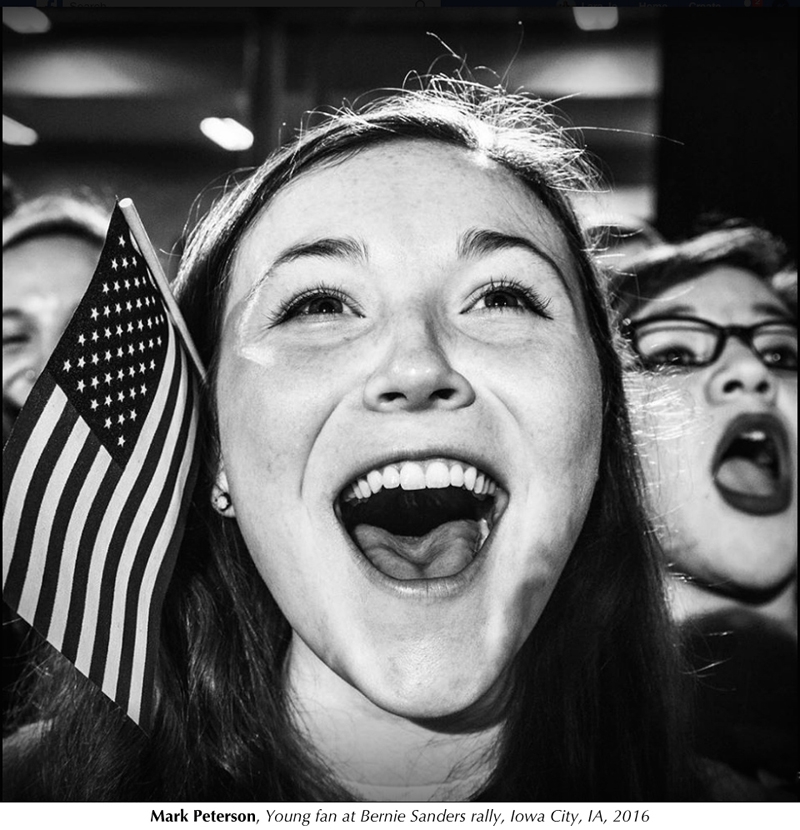

MARK PETERSON

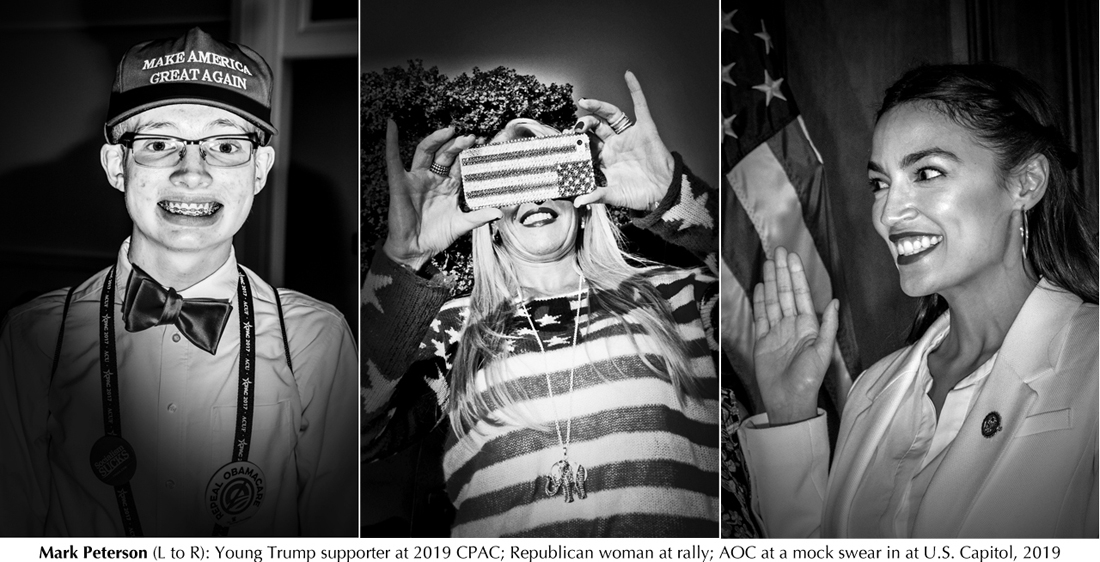

Though Mark Peterson was profiled in Part 1 of this series, his output of election photography is so prolific and longstanding that it merits inclusion on this list as well. After three decades on the campaign trail, his ability to churn out arresting political imagery week after week that still gets fast-tracked onto the pages and covers of major magazines is truly staggering, a rarity in the intense, fast-paced worlds in which he operates. Moreover, he is greatly admired by his peers, including Jeff Jacobson who considered him one of the only photographers he influenced that mastered his much-copied lighting technique and made it his own, and David Burnett, who named him as one of the political photographers he currently most admires. “I love the work Peterson has done in the last couple cycles,” said Burnett, “He makes a statement, he takes a stand, and I appreciate that. The work is very exciting.”

CHRISTOPHER MORRIS

Like Jeff Jacobson and Mark Peterson, the work of Christopher Morris also addresses the dark side of the political realm and contains contradictory layers of meaning. But unlike his two modernist contemporaries who spotlight the political underbelly with shiny surface beats, the danger is more subterranean in Morris’ images, a tonal vibration more sensed than seen. Emotions are dialed down and the color palette sublimely subdued, like a calm overcast beach day diffusing signs of a lurking storm.

His most influential political pictures are compiled in his monograph, My America (Steidl, 2006), produced while Morris was covering the White House for Time in the era of George W. Bush. He describes the book as his personal journey into Republican America. “Hopefully, he said, “you will see what I saw and feel what I felt – a nation that has wrapped itself so tightly in red, white and blue that it has gone blind.”

Morris’ photographs have also been credited with redefining political coverage in America, but a series of experimental films he made ten years later at political rallies leading up to the 2016 election are a revelation. In collaboration with Time and sound designer Edward Richardson, Morris filmed the candidates and their crowds of fervent followers with the Phantom high speed camera, then played the edited footage back in super slow motion, stretching seconds into minutes, revealing what the human eye and mind can’t see and process in real time. Coupled with the surreal soundscape made up of distorted ambient capture and fragments of stump speeches, we feel like we are floating and bobbing inside a giant aquarium of political rally creatures, undulating with swells of mob emotion.

The short film shot at a MAGA rally, simply called “Trump,” is the most powerful of the set, the foreboding fun house mirror aesthetic best suited to convey the insidious hypnotic effect Trump has had on nearly half the American population. In the slow-mo swirl of his mass seduction, fetal fascism forms before our eyes in the womb of the MAGA rally; we are inside the collective psyche of lost and wounded souls high on delusional rapture.

CALLIE SHELL

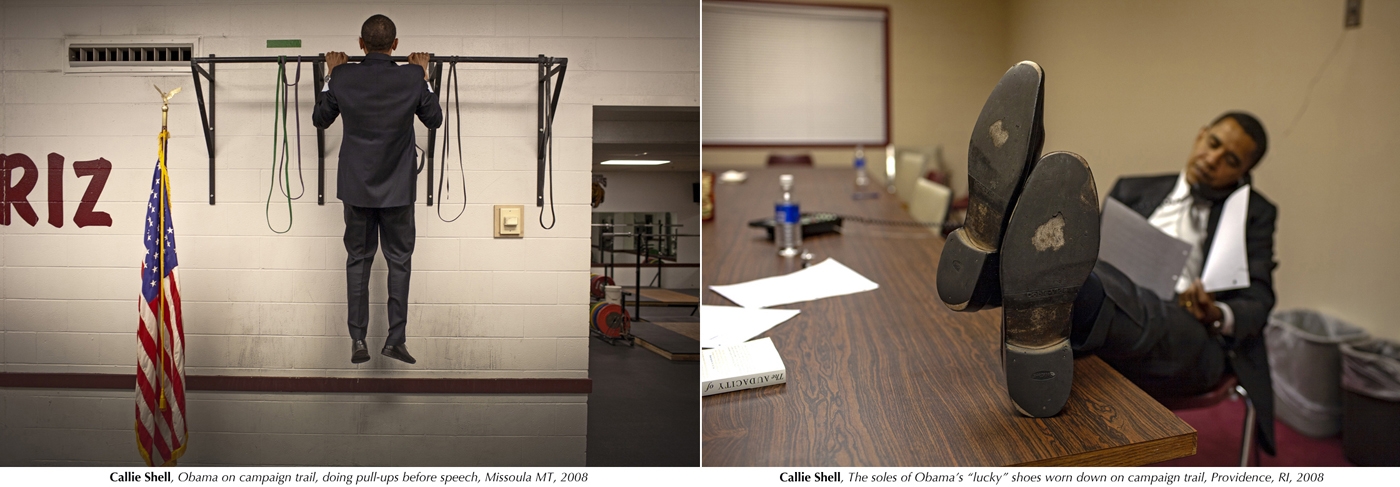

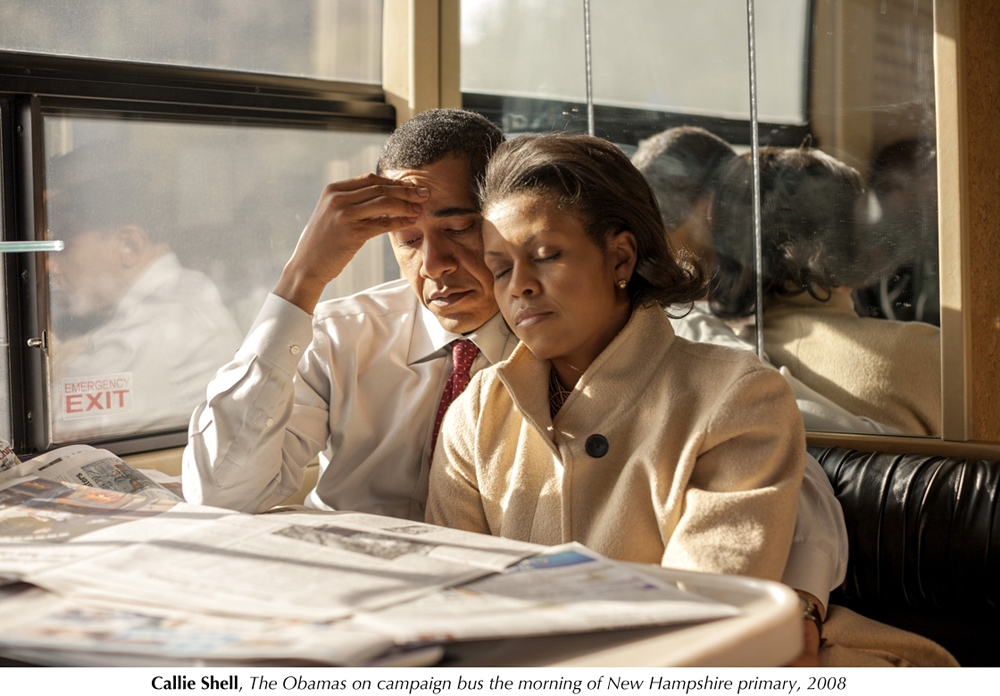

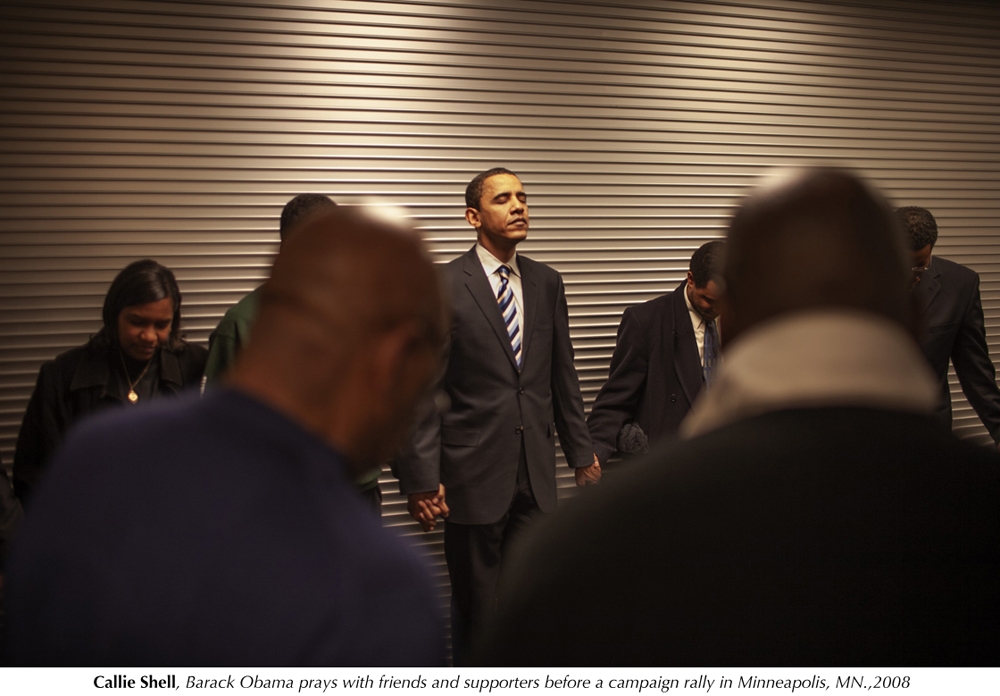

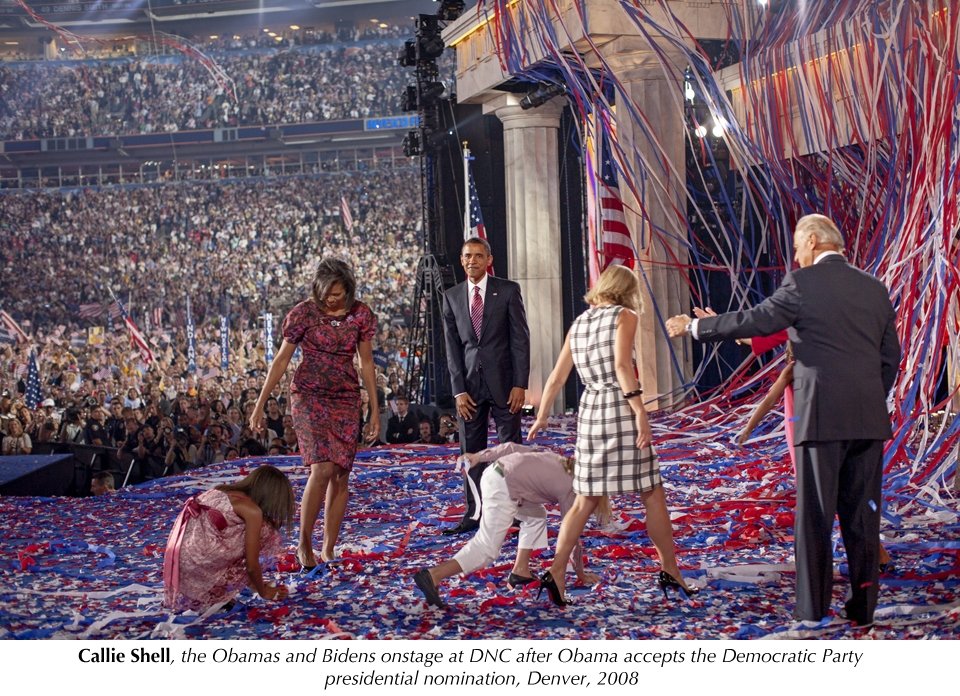

The dark, cynical currents that course through the work of Jacobson, Peterson and Morris have receded in Callie Shell’s moving, intimate portrayal of the Obamas that follows their unlikely odyssey from a local grass roots campaign – sans security, entourage and media frenzy – to the slowly growing juggernaut that ultimately landed them in the White House.

Taken on assignment for Time beginning in 2004, these deeply affecting images are by no means an obsequious idealized treatment of a rising celebrity politician the Kennedy era ushered in and the Reagan era intensified. Rather, they are a soulful reflection of the decency and hope the historic candidacy inspired and a testament to Barack and Michelle Obama’s natural capacity for love and empathy that Shell’s refined eye gently captured in their interactions with everyday folks on the campaign trail and within their family life and aspirational marriage. Interspersed throughout are other poignant images revealing how exhausting and lonely the campaign trail can be, and how hard fought was their victory.

Shell’s modern day election narrative constitutes a classic hero’s journey, commemorated in her recent book, Hope, Never Fear: A Personal Portrait of the Obamas (Chronicle Books, 2019). She makes clear the collection is not a “love fest” for the Obamas. “It isn’t meant to make us miss them more or deepen what divides us,” she states. “It is, instead, my personal portrait of a journey that changed us for the better. It is a reminder of the difference this family made when our country needed change and something to believe in.”

BARBARA KINNEY

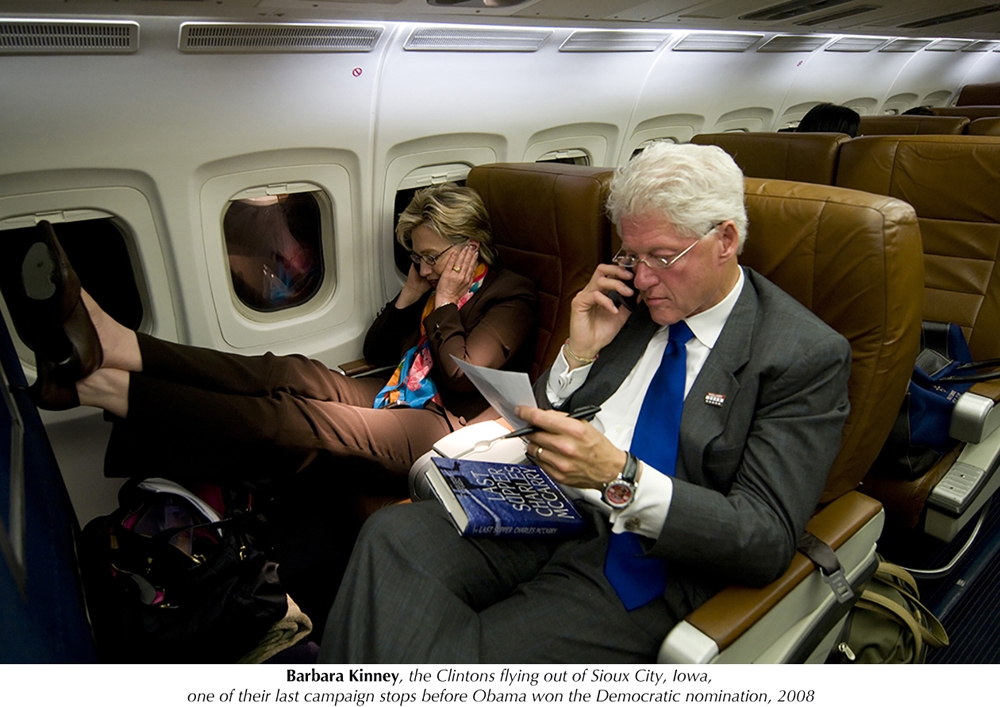

The kind of exclusive inner access Obama granted Shell is a coveted position among photojournalists, usually reserved for official White House photographers contracted to document the round-the-clock activity during a president’s tenure, including stints on the campaign trail. The seemingly plum gig comes with its comes own set of challenges, especially when the photographer is not working for outside media, but hired by the candidate to make them look good.

It’s difficult for photographers working under such controlled circumstances – where they must perpetually behave – to make unique ground breaking images without raising suspicion or alarm among elite image-obsessed politicians and their handlers. Only photographers with a high degree of social and observational skill who have built up a surfeit of trust over many years have managed to thread that shaky needle and regularly produce work that transcends the safe and expected.

Barbara Kinney, Hillary Clinton’s official campaign photographer for both her presidential runs, belongs to the small club who’ve pulled it off – her confidence seeded years earlier while serving as Bill Clinton’s personal White House photographer for six years.

Having spent years with the Clinton family, Kinney cultivated a certain level of comfort that allowed her to capture the candidate letting her guard down and letting loose. What distinguishes her campaign work (other than its obvious historical value documenting the first woman to be nominated for president by a major political party), is the high wattage of humor and rollicking fun lighting up the images, emanating from Clinton’s boisterous sea of fem fans as well as from Hillary herself. Kinney also demonstrates an uncanny ability to capture subtle but meaningful gesture and expression across all emotional ranges.

Social media has had a significant impact of the way politicians campaign and how images are transmitted to the public. Kinney was one of the first to cover politics in the selfie era, addressing the phenomenon head on with her signature spontaneity and wit. One particularly memorable shot shows Hillary Clinton facing a large sequestered crowd of supporters, their backs all turned on her with cell phones raised. This bizarre “backward” image requires a double-take to understand a mass selfie is taking place. According to Kinney, Hillary had just directed the audience to snap all at once, a savvy solution to the never-ending requests for individual selfie souvenirs.

Said Chelsea Clinton in an essay she penned for Kinney’s book, #StillWithHer: Hillary Rodham Clinton and the Moments That Inspired a Movement (Press Syndication Group, 2018), “Today, because of the ubiquity of cell phones, cameras are everywhere. We can catalogue our daily lives and moments of significance. We still need photographers like Barb to help discern when a moment illuminates a larger truth, the love between a mother and daughter, the kindness of a candidate, the joy of a campaign.”

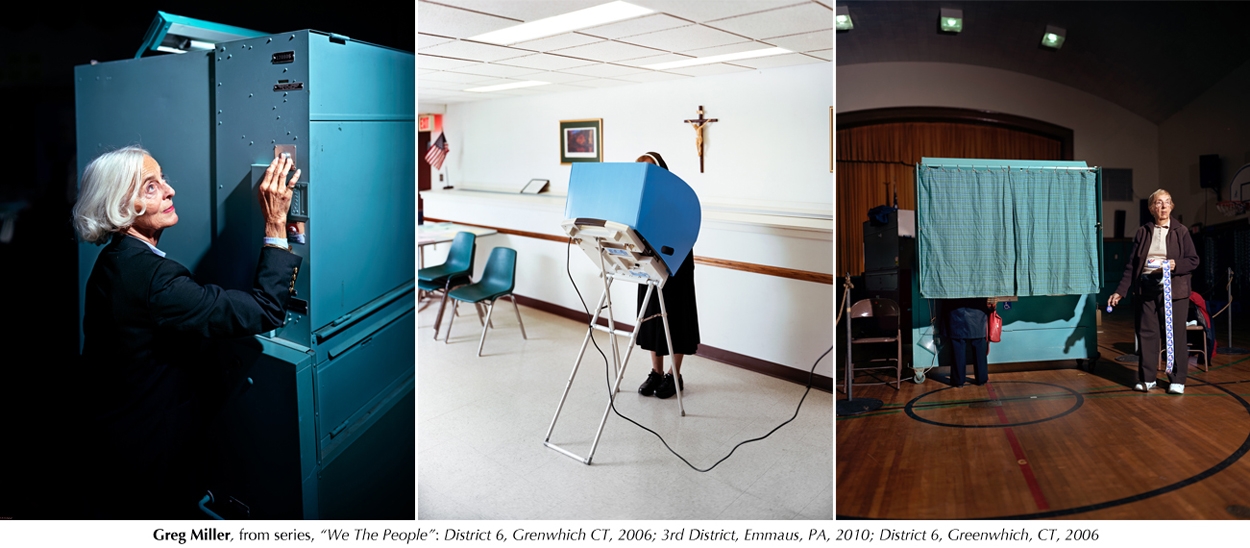

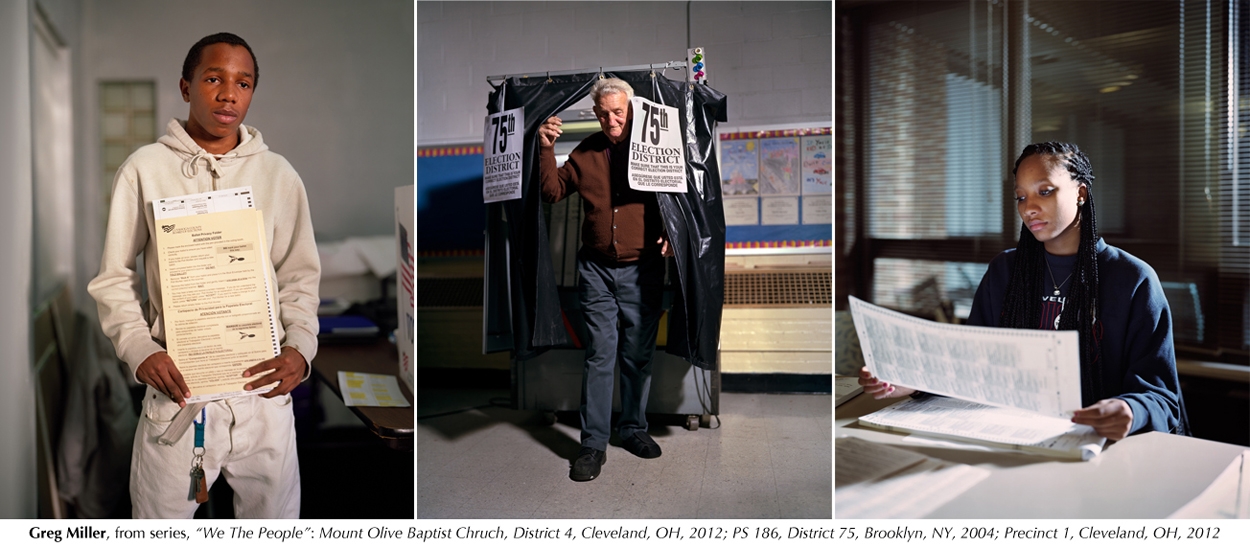

GREG MILLER

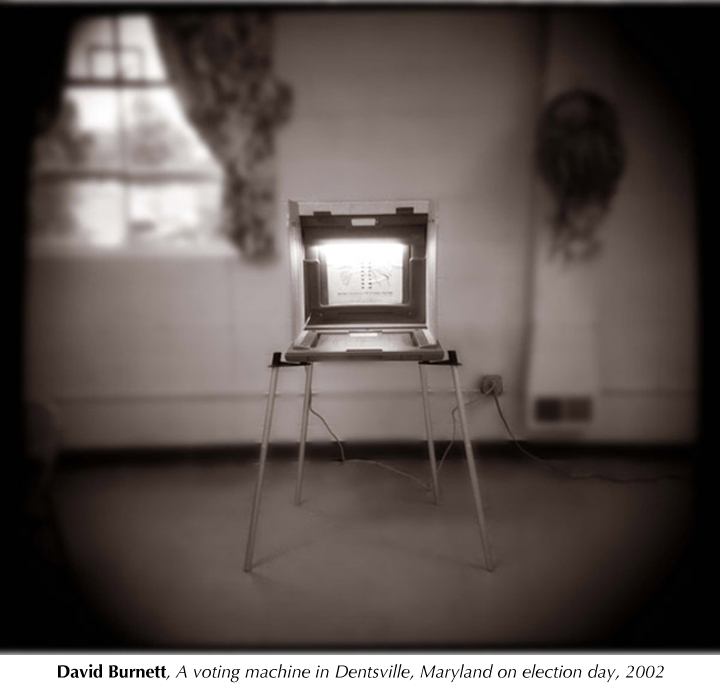

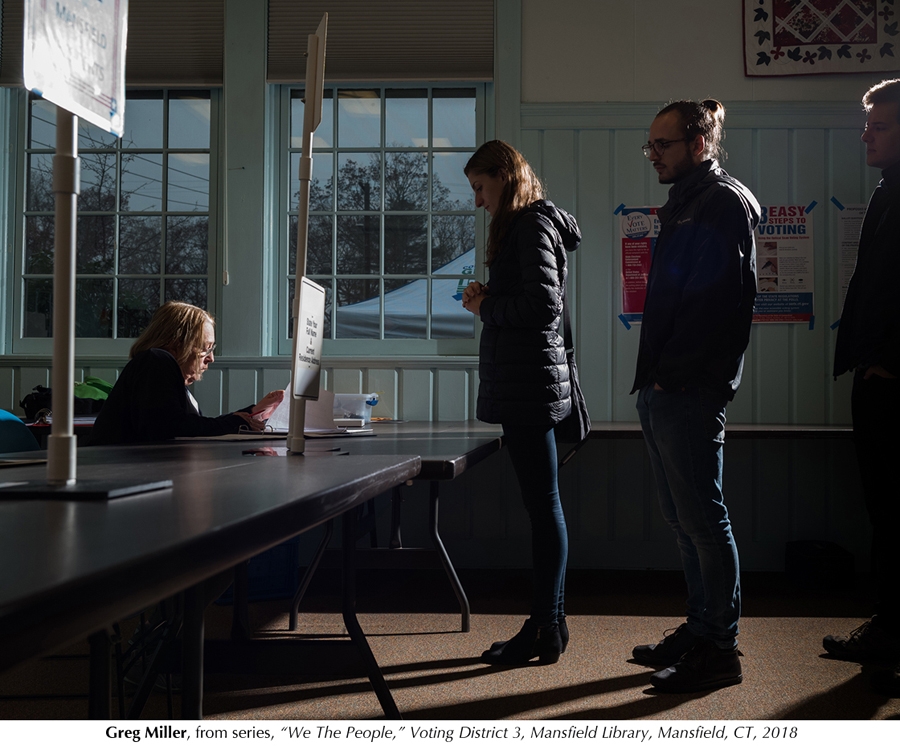

Away from the screaming crowds, media chaos and partisan bickering that dominate election season, the minimalist meditative work of Greg Miller is a poignant reminder of where the true miracle of Democracy actually takes place: inside the mundane atmosphere of polling stations where we enter a booth alone and cast our vote.

In his ongoing series, “We the People,” Miller transforms the humdrum into the holy with his use of large format cameras and narrow Caravaggio light beams aimed at voters and poll inspectors in and around voting stalls, the beatific images evoking religious confession and communion.

“That quiet library atmosphere is democracy at work” says Miller, a Nashville native and Guggenheim recipient who has photographed an eclectic array of polling stations around the country since 2004. “There is no blood bath, we don’t have to kill the king. We don’t have to topple the government All we have to do is chill out, vote quietly and accept the outcome.”

Known for his depictions of daily life that include a touching series of children waiting for the school bus on lonely back roads, Miller’s reverence for the sacred in overlooked aspects of everyday public life permeates most all his work. His appreciation for the electoral process is no exception. Says Miller, “I love the gravitas and the mundanity of it.”

ANDREA BRUCE

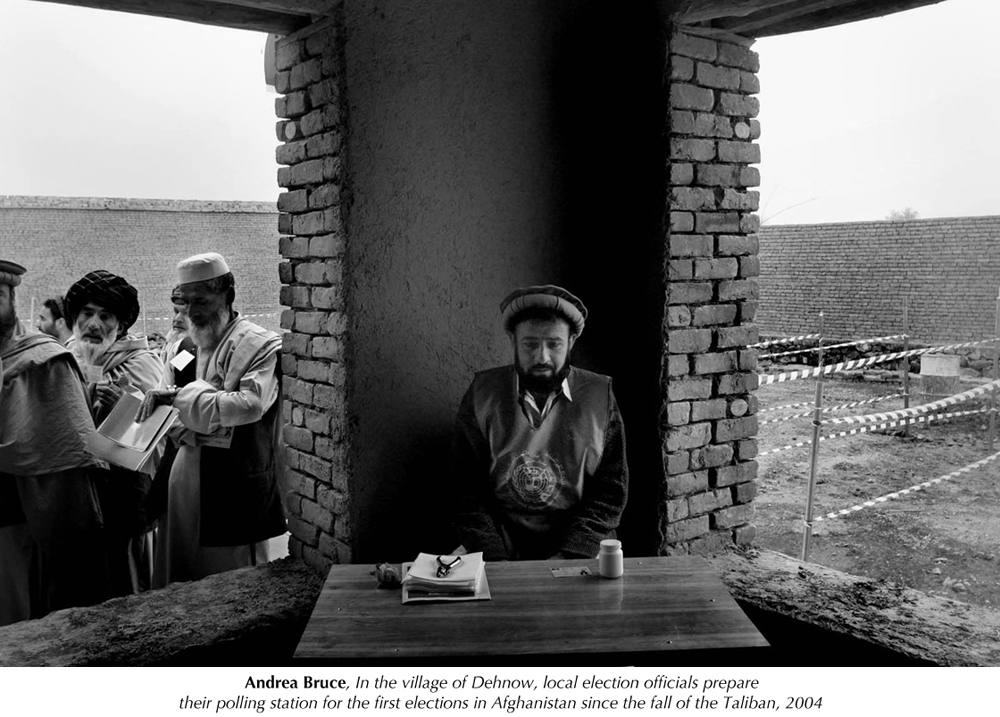

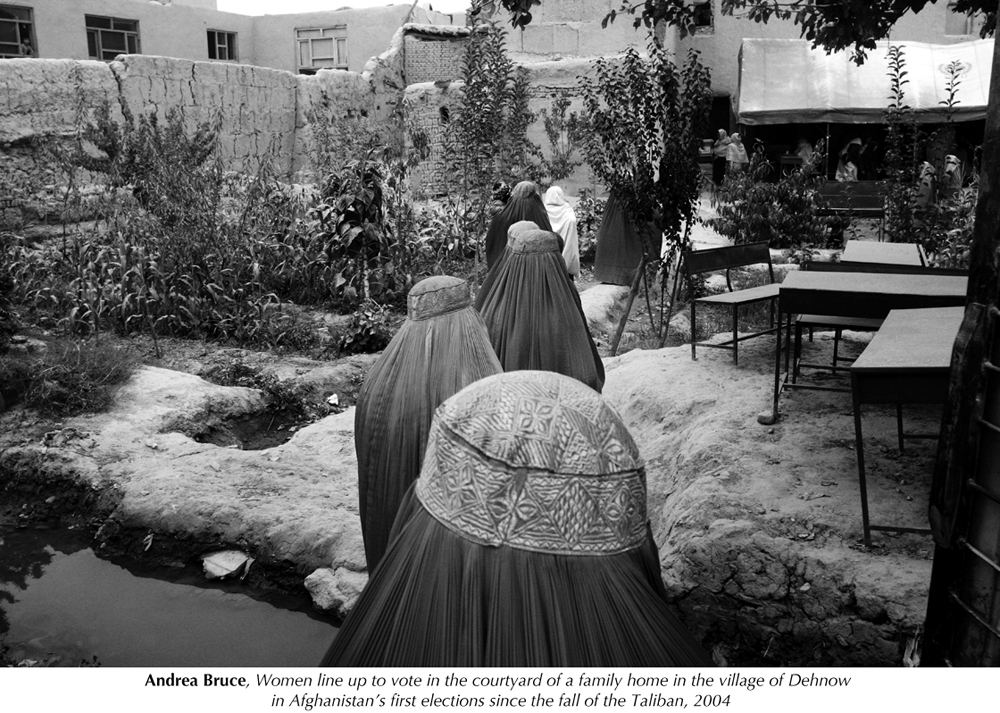

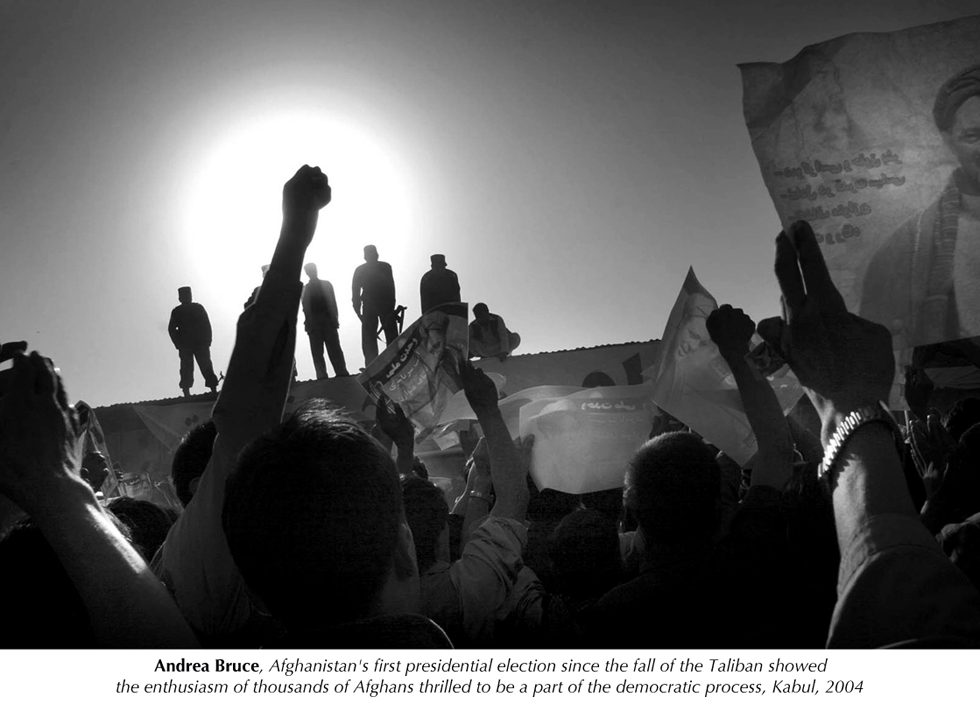

Since 2016, Andrea Bruce has been exploring ideas of Democracy and how people define the word across the U.S. in her project “ Our Democracy.” But she is best known for her work in lands far away, chronicling the lives of people living in the aftermath of war and spotlighting overlooked trauma and social issues that flare up in its wake.

Her series documenting the first free elections in Afghanistan since the fall of the Taliban is a hopeful and heartbreaking portrayal of sprouts of democracy bravely trying to take root in soil battered and hardened by war and violent fundamentalism. An especially moving image shows women in burkas lined up to vote, many for the first time, their monochromatic queue winding through a decaying stone courtyard, as if on a holy pilgrimage.

Bruce’s use of classic black and white photography for this series breaks no stylistic ground, but great photographers know when not to. Doing so in this context would distract from the profound nature of what is taking place in the pictures and its timeless, universal implications. The absence of color combined with the more archaic atmosphere of rural third world locations transport us back in time, recalling early 20th century photography picturing suffragettes still fighting for their right to vote or minorities voting for the first time. The work reminds us of how far we have come in America, while her soft ethereal exposures suggest how fragile and sacred democracy is, and how easily it could slip away.

Which historical and political imagery will stand the test of time, making it into important collections and becoming part of out shared visual history, is a complex and often controversial equation. This is particularly true in regard to photojournalism and documentary photography, whose association with current events and distribution to the masses by way of popular media has biased art-world tastemakers who often don’t perceive the beauty, significance and worth of the work until the patina of time has coaxed it to the surface. Yet numerous photographs taken in the mid 20th century by photojournalists on assignment for publications like Life magazine are now among the most treasured works in museums. After all, we cannot travel back in time to recapture moments or re-experience history. Moments only live on through photographs, offering priceless glimpses into what passed before us.