Art Basel is a world unto itself; as the 13th year of the art fair rolled through Miami in early December to strong sales, completing a re-bound from the 2008 market drop, its massive influx of cash, glamour, international speculators and celebrity have triumphantly re-shaped this beach retreat’s identity (and provided a needed form of money laundering). Lest we forget, art fairs exist for the dealers, galleries and collectors, and not specifically for the artists. As such, they specialize in providing an insular backdrop for the ultra-rich for whom art serves as a literal “selfie” in which they see their buying power reflected back to them. Art Basel (Miami) is similar to the international biennial circuit in the moneyed demographics it draws, but dissimilar in its stringent focus on marketability, commodity and avoidance of art historical context which even Art Basel (Switzerland) doesn’t quite achieve. There are alternative exhibitions and venues that provide more substance and critique—a highlight was Artadia’s 2012 awardee Ramekon O’Arwisters’ Crochet Jam at the NADA Fair—but on the whole the “gated community” feel of Miami Beach (its geographic isolation from the mainland included) doesn’t lend itself to inclusion of the world at large, not even to the local artists and galleries.

However, there were some sporadic intrusions into the gilded confines, including one by NetJets pilots airing a labor dispute, and a rather spectacular calling-out of Klaus Biesenbach at a poolside party. That same night, a coalition of local community groups and street artists marched in Wynwood, the mainland Miami location of the off-site fairs, in solidarity with the Ferguson protests and in remembrance of a local graffiti artist, Israel “Reefa” Hernandez, killed by Miami police in 2013. The organizers utilized works from artists Kenneth Pietrobono and Molly Crabapple who donated pieces, including drawings of those slain by police and feather banners with phrases such as “Brutality.” The march drew over 400 people; the protesters blocked I-195 connecting mainland Miami to Miami Beach in an effort to “shut down” Art Basel and did back up traffic across the bridges, although their impact remained contained primarily within the confines of Wynwood.

Wynwood has a history of its own; once a rundown warehouse district, it has gentrified in the years since the arrival of Art Basel as an “artist district,” no doubt in response to the amount of money flowing into Miami through the fairs. However it functions at a different level in terms race, class and economics, drawing a more diverse, populist crowd; a case in point is Wynwood’s Art Lounge, a pop-up nightclub sponsored by BET. The off-site Basel fairs in Wynwood such as Art Miami, Red Dot and Miami Project draw a similar demographic, and showcase primarily secondary market works for resale or less original, more derivative works.

What the Wynwood fairs offer are reminders that multitudes of art worlds exist simultaneously, and to be aware of the “other” in how we frame art or see art. Although the blue-chip market view is on full dominant display across the water in Miami Beach, it is only a single perspective, albeit the one of the engine at the core of the market-driven art world. As it dominates it also gives rise to the secondary market of uncontrollable replications and knock-offs in numerous hybrid forms. Comparable to the Hollywood/Bollywood dynamic, a secondary market springs from the first, which soon expands to become its own entity addressing a much larger, more diverse, democratic audience. The protests that rolled through Wynwood during the Friday evening and Sunday closing of Art Basel spoke primarily to this audience and drew interest, attention and many participants. This may have been seen as preaching to the choir, but could also be swelling the ranks of the movement. The organizers considered marching in the streets of Miami Beach for the Friday protest but felt it was inaccessible compared to Wynwood; during the Sunday rally the protesters found the I-195 blocked by not only Miami Police but by the police and mayor of Miami Beach, who were determined the march would not cross over to reach the enclosed heart of the fairs.

Traveling to New York City from Miami, the inverse relationship between these two art world centers could not have been clearer. Miami serves as the escapist pleasure-release valve for the New York art market, and what functions underneath the daily machinations of the Chelsea galleries and museum networks is on full display down south. An excellent show at Paula Cooper showcasing recent work from Hans Haacke, including his 2015 Forth Plinth proposal for the prestigious Trafalgar Square Arts Council England award, provided a glimpse of market clarity. A related show at Essex Gallery, ‘The Contract’, highlighted works by artists using Seth Siegelaub’s 1971 contract stipulating the artists’ right to a percentage of the resale value of their works (Haacke has used the Siegelaub contract for the majority of his career).

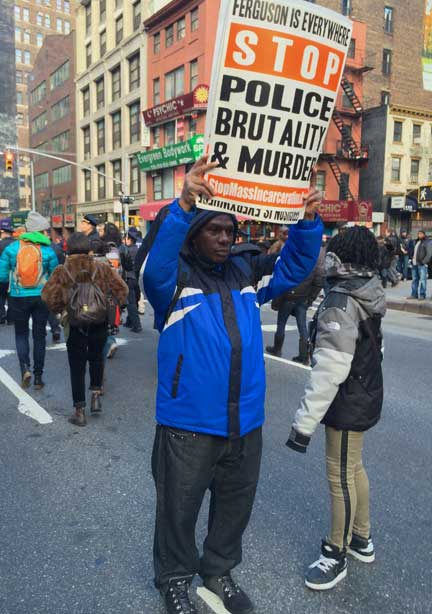

The clearest connection was between the community organized protests in Miami and the New York Millions March in solidarity with Ferguson and #BlackLivesMatter. The NYC action drew over 60,000 people; as in Miami, they also used art as an effective means to channel and direct their outcry. Large-scale mosaic murals, combined to create haunting images of Eric Garner’s and Michael Brown’s eyes, were highlighted on the front page of The New York Times; local Brooklyn resident Evan Michael Glenn walked the entire length of the march barefoot and bare-chested, performing a gesture of past and contemporary slavery. These powerful works call out the market-driven art fairs as mainly empty sites whose meaning is desolated by market forces, driven out by an avoidance, or arrogant ignorance, of current events in the larger world enclosing them.

Photos by Nancy Popp