Paul Anthony Smith is a Jamaica-born, Brooklyn-based artist who digitally composites photographs of people (family, friends and strangers), as well as places (Jamaica, Brooklyn and Puerto Rico), then decorates the surface of the paper with a stippled pattern by piercing it with a sharp tool. Smith shoots on location during his travels, making photographs of individuals as well as demonstrations and parades. The artworks reference Smith’s Jamaican-American heritage, while simultaneously alluding to world-wide racial and political tensions.

The “picotage effect “ (an old-fashioned pattern created by using a stipple method in textile printing whereby brass pins are driven into wooden blocks, which are used to create highlights and shadow patterns on fabric) that covers the photographic surfaces is based on Dazzle camouflage—patterns used to hide ships during World War I. Smith is purposeful with this and other references, directing viewers toward ideas on anonymity and hiding in plain sight.

Smith’s work investigates the formal relationship between image and pattern wherein the angular piercing of the images creates an animated quality similar to lenticular photographs. Smith’s pieces however, are also firmly rooted in the culture of appropriation. Given that he begins with his own photographs, what exactly is Smith appropriating: the readymade patterns of Dazzle camouflage, the layering of photographic imagery with geometric shapes (similar to Wade Guyton) and the aesthetic of juxtaposing the personal and historical (like Adam Pendleton)? While Smith’s pieces are uniquely his own, they also share a kinship with Robert Rauschenberg.

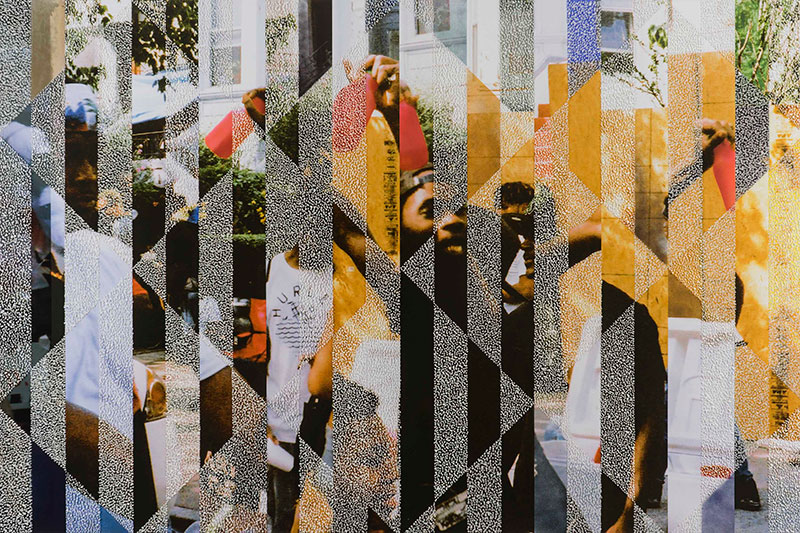

Paul Anthony Smith installation view. Photo by Michael Underwood. Image courtesy of Luis De Jesus Los Angeles.

In Departure Amputated, (all works 2018, except where noted), a vivid color photograph of a lush green landscape surrounded by a cloudless blue sky is intercut with people at a festival. Vertical stripes of punctures from the rear of the image reveal the white backside of the paper. Smith employs the same strategy in Cosmos and The Violence of his embrace of things American is embarrassing. The latter is a black-and-white photograph of a funeral. Many of the figures of those attending are obscured by the pattern overlay, rendering the purpose and context of the original image ambiguous.

Smith’s portraits are more direct than his images of places. The whites of the subject’s eyes stare from beyond the stippling, which functions both as pattern and a prison in Visibility comes at a cost. In Fear on the Hill and Grave Yard and Fallen Mango, the textured disruption of the photograph parallels the way the light falls on the trees in the background. The images capture the tension between violence and serenity. As directed by their titles, these seemingly peaceful portraits have an air of disquiet.

In addition to the picotage photographs, Smith also presents silkscreens on canvas from a 2017 series titled “Grey Area.” These atmospheric pieces are comprised of grids of disjointed and fragmented halftones depicting both palm trees and people drawn from Smith’s birthplace. The images are visually and conceptually engaging while serving as conduits to link Smith’s memories and cultural heritage.

0 Comments