Shortly after Thomas Kinkade died tragically from an overdose of Valium and booze in April 2012, LA artist Jeffrey Vallance had a dream in which Kinkade showed him a secret vault of disturbing artwork that ran counter to the wholesome, uplifting image cultivated around the Painter of Light™ and his artwork during his lifetime. To Vallance’s astonishment, when he recounted the dream to Kinkade’s family during a symposium on kitsch a few years later, it turned out that the vault really existed, and indeed contained a mother lode of non-canonical Kinkades.

In Miranda Yousef’s new documentary on Kinkade, Art for Everybody, Vallance tells the story of his prophetic dream again, and she uses the vault and its contents as a metaphor for Kinkade’s barely repressed darker side, and the toll his industrialized and sanitized version of professional painting took on himself, his family, his business partners and his legions of fans. Piecing together Kinkade’s career from talking heads, archival footage and the full cooperation of his widow and four daughters, Art for Everybody doesn’t break any new cinematic ground, but is a tightly constructed narrative.

Vallance befriended Kinkade while organizing the museum-scaled exhibition “Thomas Kinkade: Heaven on Earth” at Cal State Fullerton’s Grand Central Art Center in 2004—a testament to Vallance’s uncanny ability to insinuate himself into unlikely situations and make improbable connections, such as trading neckties with Anwar Sadat, curating contemporary art exhibitions at the Liberace Museum, delivering XXXL scuba flippers to the King of Tonga, and so on.

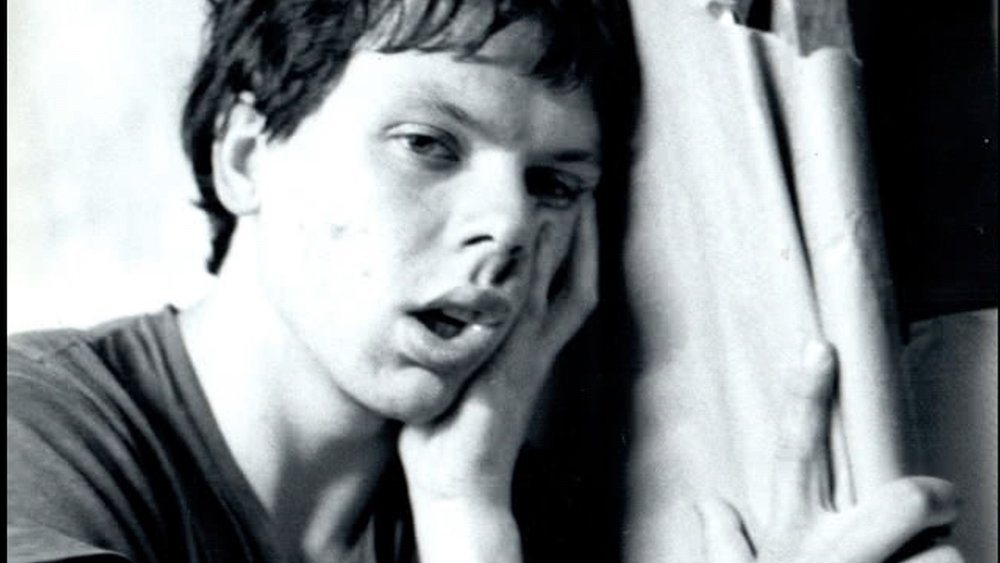

Still of Thomas Kinkade.

If you are unfamiliar with Kinkade, the incongruity stems from the fact that his paintings (as I noted in an essay published over two years before Susan Orlean’s New Yorker profile, AHEM!) are “overtly, even militantly sentimental… detailed workmanlike renditions of traditional quasi-luminist landscapes, inhabited by homely cottages and stone lighthouses, neatly bisected by babbling brooks and waterfalls, and track-lit from heaven through a conveniently parting storm-front.”

Beloved by the Moral Majority, his career was subject of one of the most intensive and successful branding campaigns in the history of art. At the time, it was guesstimated that 1 in 20 American homes contained a Kinkade artifact, which encompassed anything from a hand-retouched limited-edition print to coffee mugs, collector plates, datebooks and customized La-Z-Boy recliners.

Kinkade grew up poor in Placerville, California, about 40 miles east of Sacramento, attended Berkeley, then Art Center in Pasadena. After graduating he landed a job painting backgrounds for animator Ralph Bakshi’s cinematic collaboration with comic artist Frank Frazetta, Fire and Ice. Bakshi is the most entertaining interviewee: “From what I gather, if you like Kinkade you’re an asshole. Well, I guess I’m an asshole.” This period of Kinkade’s life is the most revelatory, with snapshots of the artist in Rocky Horror drag, stories of mental breakdowns and the most intriguing of the previously unknown work that was discovered in his vault.

While the artist’s shady business deals, debilitating alcoholism, sexual assaults, bizarre alter egos and family-unfriendly outbursts (like pissing on a Winnie-the-Pooh statue in Disneyland or yelling “Codpiece! Codpiece!” during a Siegfried & Roy performance in Vegas) are documentary gold—the real shocker for most visually literate viewers will be how accomplished a painter Kinkade actually was.

Thomas painting with baby.

Many of his undergrad paintings are tortured self-portraits in the familiar Degenerate Art mode. “I want to paint the truth,” he says in a contemporaneous audio journal, “and the truth of this world is not happiness. The truth of this world is pain, and that’s the only truth.” But he’s also a stylistic chameleon, knocking out underground-cartoonish paintings or Gustave Caillebotte homages at the drop of a beret.

This, in turn, forces us to reconsider Kinkade’s primary oeuvre—the over-saturated, over-articulated, nostalgia-curdled landscapes—as a deliberate concept-based aesthetic strategy, rather than someone earnestly trying and failing to be Albert Bierstadt. Of course, this won’t be enough for everyone. The always droll Pulitzer-winning LA Times critic Christopher Knight, brought in as resident nay-sayer, doesn’t miss a beat when shown some of Kinkade’s early work: “He should’ve stuck with it.”

Ultimately, Art for Everybody comes across as a cautionary tale about the conflation of artistic ambition with the capitalist myth of infinite (and mandatory) economic growth. Which may also have been part of the artist’s intention. “His paintings are a brilliant look at America,” asserts Bakshi. “He’s really painting his feelings about the cheapness of our society as it becomes more greedy and hungry. Those paintings belong in The Metropolitan Museum of Art as far as I’m concerned.” I wouldn’t bet a million bucks on that, but maybe they’ll work up the nerve to screen this moving and challenging documentary.

Art for Everybody premiered in March at SXSW and is currently traveling the Festival circuit. Jeffrey Vallance is working on curating an exhibit of Kinkade’s never-shown vault paintings.