Viewing art is often followed by epiphanies—moments in which the viewer understands things both cognitively and perceptually. Sometimes it even provides a glimpse into another place, at another time, about which one does not yet have any real experience. “The Shape of Time” is one such exhibition in which the number of new thresholds crossed is many. The artworks themselves are exquisite and extraordinary, ranging in techniques to include ceramics, sculpture, painting, fiber art, photography, installation, video and performance. Thematically broad, too, the exhibition emphasizes the economic, sociological, cultural and aesthetic. It is through the work of curators Elisabeth Agro and Hyunsoo Woo that the exhibition opens itself to the imagination, both aesthetically and historically.

It is impossible to summarize what Korean art after 1989 means because of the complexity and quantity of events that were occurring in the country at that point. Suffice it to say that the works of the thirty-three artists included in “The Shape of Time” reflect the myriad of changes in the country following the 1980 Gwangju Uprising and the 1988 Seoul Olympics, when a newly democratic South Korea moved out from under a dictatorship and opened up to the rest of the world. Most of the artists featured came of age during this period, and their works reflect the major shifts in the region.

Some of the artists, like Do Ho Suh, have already exhibited in the United States. Suh’s ethereal fabric building Seoul Home/Seoul Home/Kanazawa Home/Beijing Home/Pohang Home/Gwangju Home/Philadelphia Home (2012) floats in one of the museum’s main halls in a manner both majestic and melancholy.

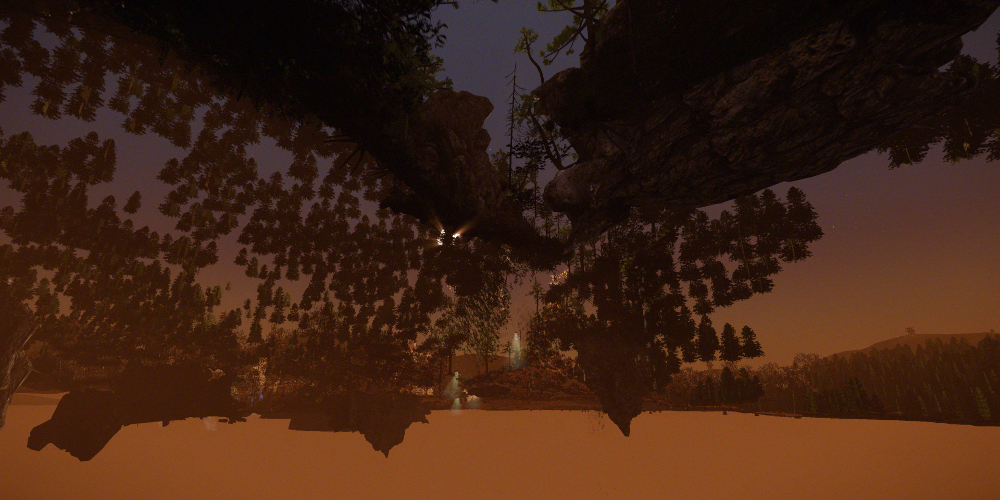

Still from Hayoun Kwon’s film 489 Years (2016).

Other artists, like Kayoun Kwon, may be entirely new to viewers. One of the most compelling works in the exhibition is her video, 489 Years (2016). The projected video is a virtual reality walkthrough of the DMZ (demilitarized zone) that separates North and South Korea, based on the account of a soldier who would regularly go on missions there. The landscape is both eerie and lush, the projection of an unreal fantasy that explores without hyperbole one of the most dangerous places in the world.

A table-sized installation, Evanescent Landscape—Hwigyeong: Philadelphia (2023) by Juree Kim relates more directly to changes that are both catastrophic and prescient. The piece is a constructed clay model of a modern city that has had water poured on it, causing the inevitable dissolution of the unbaked material into a present-tense ruin. Fragments of houses and offices jut out here and there, recalling both the urban transformation that the artist lived through and our current global climate concern about how nature is transformed by economy and technology.

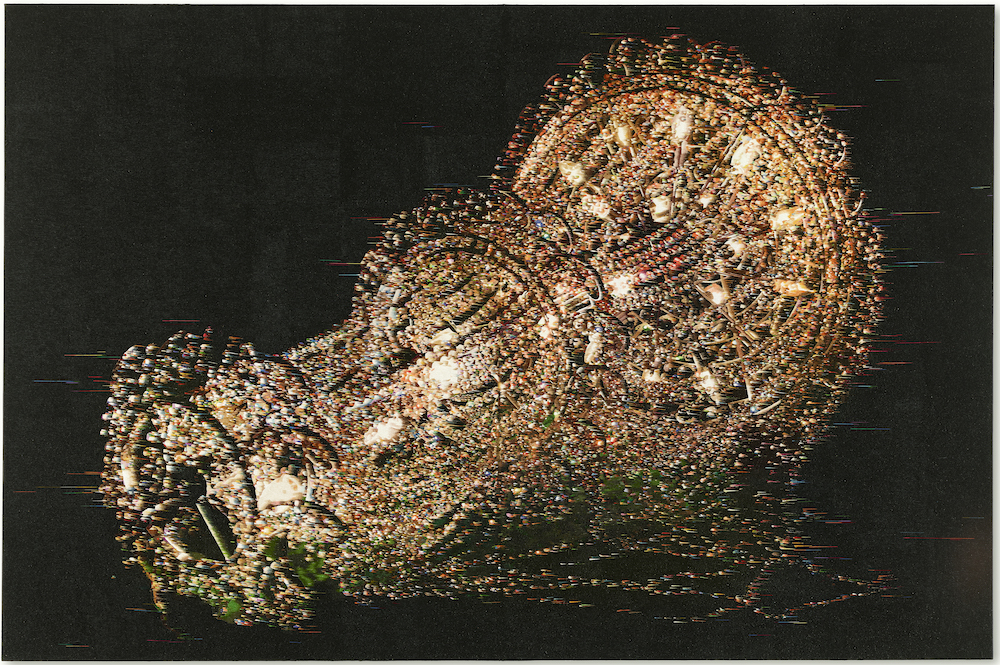

Kyungah Ham, What you see is the unseen / Chandeliers for Five Cities, 2015-2019. Courtesy of the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

At first glance, the works from the series “What you see is the unseen / Chandeliers for Five Cities” (2015-2019) by Kyungah Ham appear to be embroideries stretched on frames depicting luscious chandeliers that have fallen over or been unmoored from their usual positions in. Ceiling. As it turns out, to make these Ham goes through the very complicated process of getting these source images from South Korea (where she works and lives) to North Korea where the embroidery is completed by hand. The metaphor of luxurious but disheveled structures is a part of the conversation surrounding the series, but of equal importance is the information contained in the labels. It is there that the entire transactional process is summarized including both material and social parameters such as North Korean hand embroidery, silk threads on cotton, middleman, smuggling, bribe, tension, anxiety, censorship, ideology and wooden frame.

Overall, the exhibition is an intricate and profoundly significant aperture into a much larger world. It provides access to captivating art and is an invitation to further explore contemporary Korean art. This is but the first of several significant exhibitions in the United States in which art viewers have a chance to delve into Korea’s cultural production. “The Shape of Time” is a very auspicious start, and one that viewers should try to experience.