In “Monsoon Season,” her first ever New York solo show, on view at Charles Moffett, Natalie Strait presents new paintings of women that explore climate change, gender, queer culture and the experience of being a woman today. The women in Strait’s paintings are all shown alone or in pairs. Every figure is depicted topless, though this fact seems almost inconsequential. Their bare chests are not exaggerated or made to draw attention, but rather normalized and presented with the same straightforward, matter-of-fact treatment as the rest of their bodies. Strait’s subjects derive from media and popular culture. She takes inspiration from the long legacy of the female body being put on display for consumption. From vintage photography to Playboy to advertisements and social media of today, the image of the female body has been objectified and consumed. The works in the show seek to break down some of the tropes and visual cues used to create identity. Reclaiming the male gaze, Strait avoids over-sexualizing or objectifying her figures. Rather, she navigates the complexities of being a woman who is at once confident and vulnerable.

The exhibition title, Monsoon Season, reflects the period of heavy rain in Strait’s native Phoenix, an annual occurrence that locals have come to rely upon for respite after the summer. As with the rest of the world, Phoenix has seen the effects of climate change and now experiences reduced monsoon seasons, if any, leading to increasingly arid land and fires, along with the polluted skies that follow. A hazy, smoky landscape is seen in Superstition (2022), in which a woman holds a chihuahua in front of what appears to be an actively burning hill. Though a shocking, devastating site to behold, the scene is familiar both in Phoenix and in Los Angeles, where Strait lives and works today. The figure’s apparent indifference to the smoky sky attests to the increasing normality of such a phenomenon.

Natalie Strait, Superstition, 2022. Image courtesy of the artist and Charles Moffett.

A similar sky is seen in the background of Day Off (2022), in which a reclining woman lounges against a chain-link fence. The position and form of the figure in Day Off, seen also in Electric Blanket (2022), recall the relaxed, recumbent women that were favorite subjects of famed sculptor Henry Moore. Strait’s reclining figures might also bring to mind Aristide Maillol’s cast lead sculpture, L’Air (1938, 1962), that greets visitors to the Getty Center in Los Angeles. Modern imagery like a bag of Cheetos and an industrial cityscape reinvent the reclining woman trope with a contemporary twist.

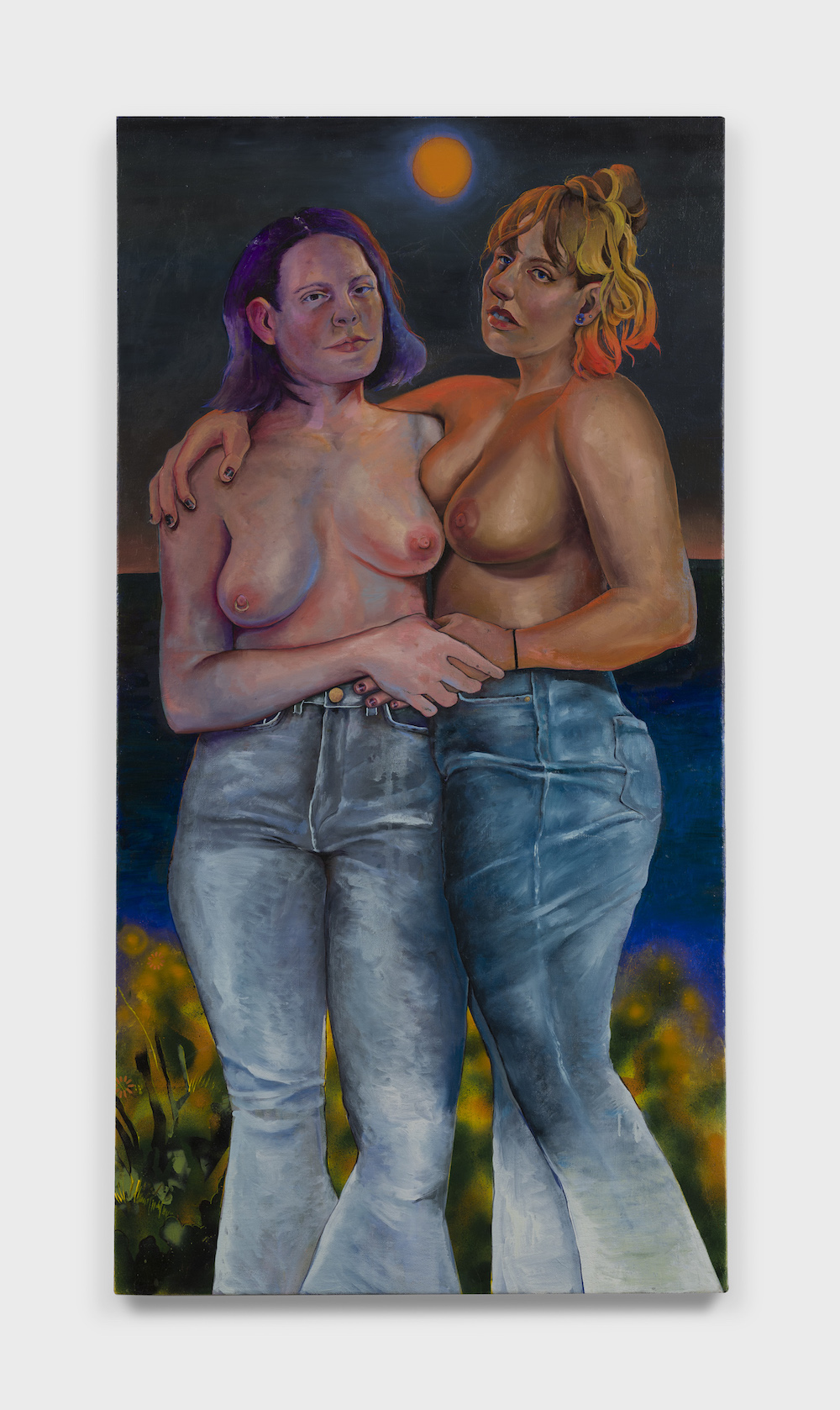

Such statuesque forms appear throughout Strait’s works, in particular the two semi-nude women in Moonrise on the Lake (2021). Standing in a half embrace and holding each other’s hand at waist-height, the two figures appear to be posing for a classical portrait. They look relaxed and self-assured, yet the clasped hands are protective, acknowledging their vulnerability as they pull each other in closer. The figure on the right looks off into the distance while the figure on the left looks directly at the viewer with an ambiguous, semi-guarded expression. Somewhat stoic, her face is also soft and tired, as if prepared to defend herself and her companion, yet retaining the capacity to let the viewer in.

Natalie Strait, Moonrise on the Lake, 2021. Image courtesy of the artist and Charlie Moffett.

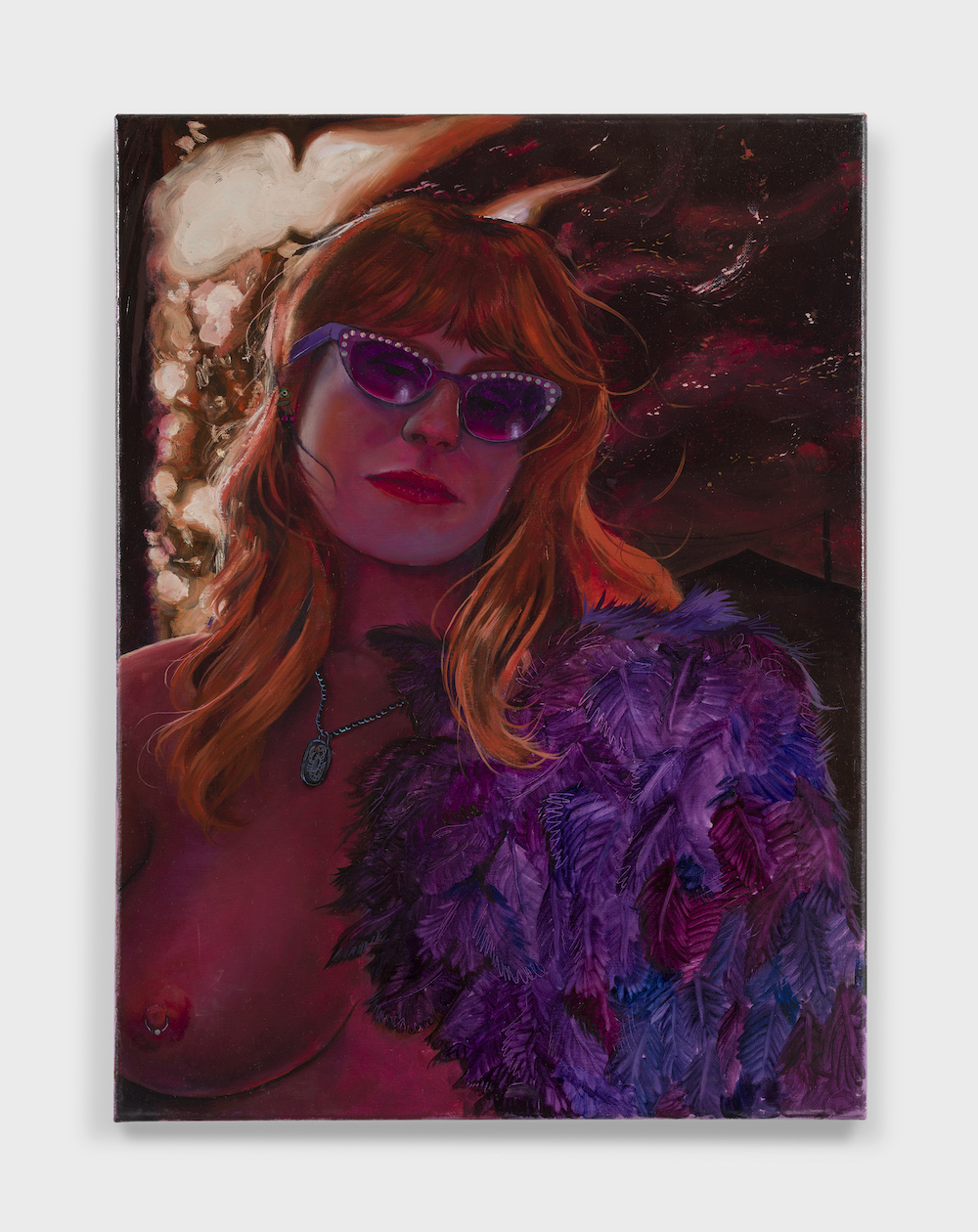

Subtle embellishments appear on select works, such as the tiny, glittery sequins outlining the top of a pair of pink cat-eye glasses in Palm Tree Fire (2022). Worn by a strawberry blond woman with bangs, the sparkly details draw the eye to the figure’s face. The work shows Strait’s exploration of the visual cues we use to define our outward appearances. The figure holds what appears to be a purple, feathered pom-pom or boa, and her bare nipple reveals a piercing. These objects, easily exaggerated to sexualize a woman, are all subtle and matter-of-fact. One could undoubtedly find a spread in Playboy with identical items, yet the figure appears to be wearing them for herself rather than to excite a viewer. Even the vantage point–slightly under her chest and tilted upwards–is a position that could be interpreted as sexual. However, Strait denies the viewer the authority to sexualize the imagery. Instead, the woman retains the power to be sexy if she wishes, or just exist in her semi-nude glory.

Natalie Strait, Palm Tree Fire, 2022. Image courtesy of the artist and Charles Moffett.

If “Monsoon Season” represents Strait’s entrée into the New York art scene, it is undeniably a strong, successful one. Strait’s style is fresh, and her talent is unwavering. Above all, the issues she addresses and her navigation of the world as a woman are increasingly crucial as we see our rights challenged and stripped away.

Monsoon Season is on view at Charles Moffett, 431 Washington Street, New York through August 5th