One could see the LA-based artist Jesse Mockrin’s decision to name her first solo exhibition in New York City and at James Cohan—“The Venus Effect,” after the art historical term, motif, and visual effect—as itself a gesture towards acknowledging, even inviting ambiguity in the reception of her work. After all, the so-called ‘Venus effect,’ such as it is understood, achieves conceptual coherence only through particular scaffolding, at once disparate and contingent. Found throughout the very Renaissance-era portraiture of women that has inspired Mockrin’s work, the Venus effect refers to the employment of mirrors by painters, almost exclusively men, to reflect their female subjects, effecting an objectification fit for the male gaze. Within this reflection, however, the viewer should be able to surmise the female subject is not —perhaps only—looking at herself, but could be looking at them, if not originally the work’s creator. The encounter between perspectives orchestrated may have a beguiling effect, but ultimately the maze of gazes reveals one over the rest, sustained by the historical structures of power operating behind gender. The Venus effect is often tied to the proposition that what one believes may not correspond to reality. Its concerns reach beyond that of the artistic or historical, into the scientific and psychological. Indeed, Mockrin’s newest body of work holds promise to be about so much more than just its namesake.

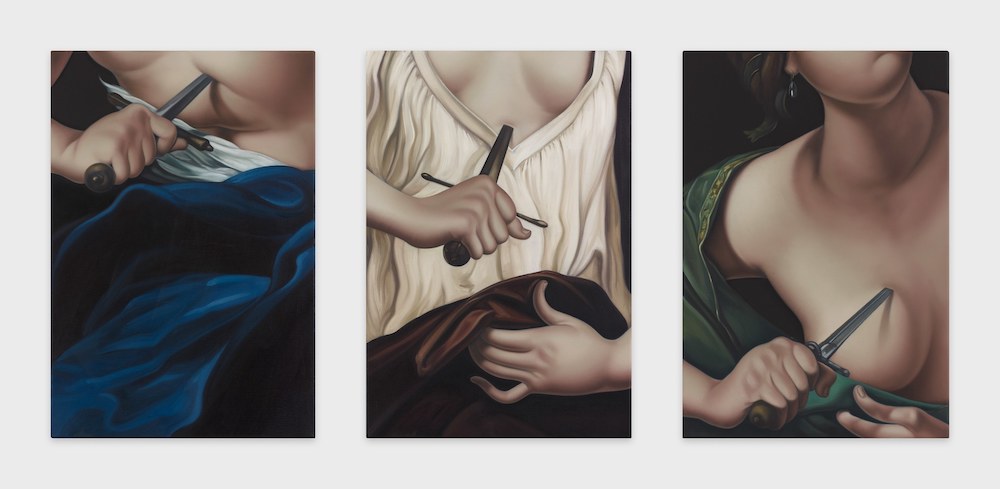

“The Venus Effect” has been installed within the James Cohan gallery so that each of its 10 paintings (all 2023) is given ample space for presence and viewing, no matter the size. All of the paintings have also been hung at heights ideal for most full-grown viewers to meet the main contents at eye level. Three are diptychs, larger in size than the rest. A handful of drawings on paper accompany the exhibition, titled, and depicting, Women grieving. It should be safe to say, as well, that by this point in her career, Mockrin has developed her own singular, or signature, style. By her own admission, Mockrin prefers more defined line work, her faces and bodies are idealized, echoing a Mannerist aesthetic, ironic, reflexive, and all, her rendering of human skin is perfectly unblemished, unreal, the result of layers of oils procedurally applied. The lighting in Mockrin’s paintings is always impeccable, true to her source material, and the better to highlight the ever-present and animated textiles, as in curtains, or the folds of clothing, and more often than not, their floral decoration. Mockrin’s compositions are often informed by the practice of cropping, if the human figure is not the focus of a given painting, a detail is, with hair and hands peripheral and cut off. Finally, the femininity on display in Mockrin’s paintings is not so much portrayed as interrogated. All if not most of these aspects are prevalent throughout the exhibition.

Jesse Mockrin, The gaping wound was exposed for all to see, 2019. Courtesy of James Cohan.

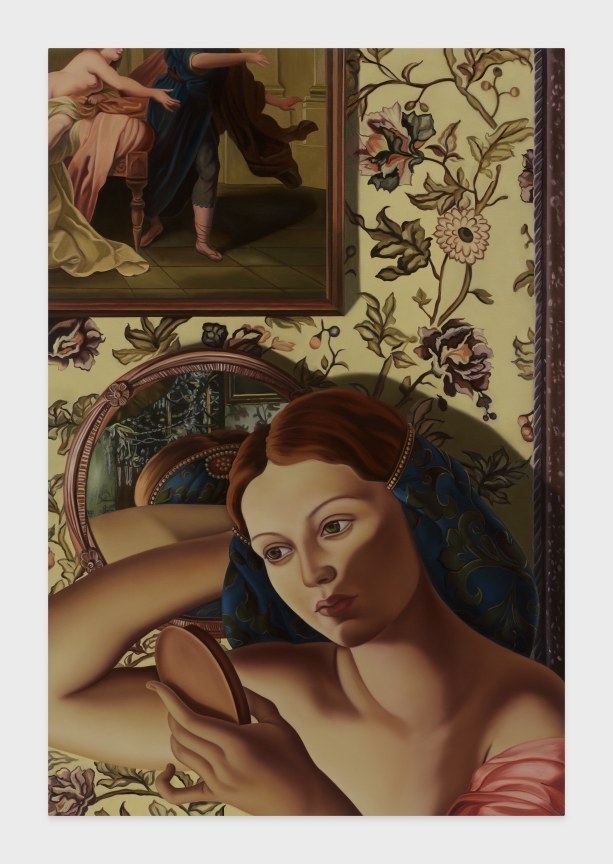

Whether intentional or not, one of the first paintings the viewer is likely to meet in “The Venus Effect” is also among the more audacious. In Herself Unseen, a woman’s sideways profile occupies the bottom half of the composition, she poses her hair with one hand, while attentive towards a small mirror held with the other. Just behind her, another mirror reflects the back of her head, and the room she’s in, instead of the viewer, or Mockrin. Above her, the corner of a Renaissance painting peeks out, depicting a barely clothed woman reaching for another figure, possibly a man, who swats her away. In fact, frames—or crops?—abound, perhaps five in all. One seems to line most of the actual canvas’s right-side frame, and another is hinted at in the wall mirror’s reflection. A floral-decorated wallpaper field and antique light tie everything together. The viewer is left to ponder on the nature of framing or cropping, the question of what is included, what is left out, what is focused on and what is dismissed, namely, perspective as understood expansively yet critically. Many of the other paintings follow suit, taking up different aspects or concerns set down here. In Divination, Mannerist-style boneless arms and hands prop a mirror up, against an upside-down V-opening of curtains, and resting on a sheen surface, both decorated in floral, all of it bathed in a cold blue light. The posing of the arms is unnatural enough to highlight the composition’s framing. Much the same effect is present in “Sorceress,” where yet again, impossibly curved, bent hands pose with long wavy red hair and hold up a mirror, presumably for a face outside of the frame. Almost every surface in the room, including the hand-held mirror, has floral decoration, beautifully highlighted by sunlight streaming through a window.

In the eponymous diptych, Mockrin utilizes the gap between the two paintings to question their cumulative coherence. On the left, sunlight hits heavy drapery, a clothed arm lifts some of it up from the left, while a naked woman poses and looks at something out of frame to the right. On the right, beautiful green drapery divides perhaps that naked woman’s holding of a mirror, reflecting a, or her own, face, gazing directly at us, from an unclothed arm lifting some of it up. Taken together, it is as if the scene were a narrative loop. Presumably, we are situated in the room with them, and this is made even more surreal by the detail of a garden just outside the window, beyond our subject figure(s). If not audacious, one of the more ambitious paintings in “The Venus Effect” is The lover and the beloved, where the diptych gap suggests an in-between mirror, only to come into conflict with the daylight that streams in progressively from left to right. In both parts, a seated woman gestures down to a seemingly admiring male below her. On the left, the woman holds the mirror, the man’s back is turned to us. On the right, the male is facing us, and he is the one holding the mirror. The painting is inspired by an Italian epic poem set during the Crusades and involves chivalric knights and treacherous witches.

The paintings of “The Venus Effect” hold an abundance in potential for interpretation. What do we make of Mockrin’s highlighting of the act of cropping and framing? Furthermore, what does she want us, the viewer, to pay attention to? How can the viewer read the inclusion of snippets from famous Renaissance-era paintings and their exclusive focus on gender dynamics? Why are the people in Mockrin’s paintings modeled after the Mannerist aesthetic? Some contemporary interpretations argue Mannerism has a self-conscious, reflexive, proto-(post)-modern character…What of their unnaturally perfect skin? Why do some of her subjects defy the traditionally imposed gender dichotomy? What about the recurring gender role reversals that occur in her paintings? What kinds of questions does Mockrin have for the historical and social construction of femininity? In referencing Renaissance art as source material, is Mockrin reviving an antiquated vision for a twenty-first-century audience just to see what the reaction is? Or is satire perhaps one of her aims? Critique? The nature and execution of Mockrin’s project, overall, is such that no matter what explanations or interpretations are offered up, still others will present themselves. This is, of course, to the artist’s credit.