The woodblock prints by American painter, Frankenthaler (b. 1928) that form “Radical Beauty” at Dulwich Picture Gallery in London, follow the wave of recent retrospectives highlighting overlooked 20th-century female artists such as Hilma Af Klimt and Agnes Pelton. This exhibition, much like Matisse’s The Cut-Outs, centers on a medium the artist was lesser known for but may come to be their standout and most memorable work—as I believe for Frankenthaler it should be.

The exhibition features prints created from many layers of woodblock prints, allowing for depth in the colors from the layering prints and wood textures. The color palettes resemble night skies, sunsets, how clouds look out of an airplane window. That is to say they are vast. The feeling I get throughout this exhibit is similar to being in nature with awe-striking landscapes: I tingle, get teary, and feel a little aroused.

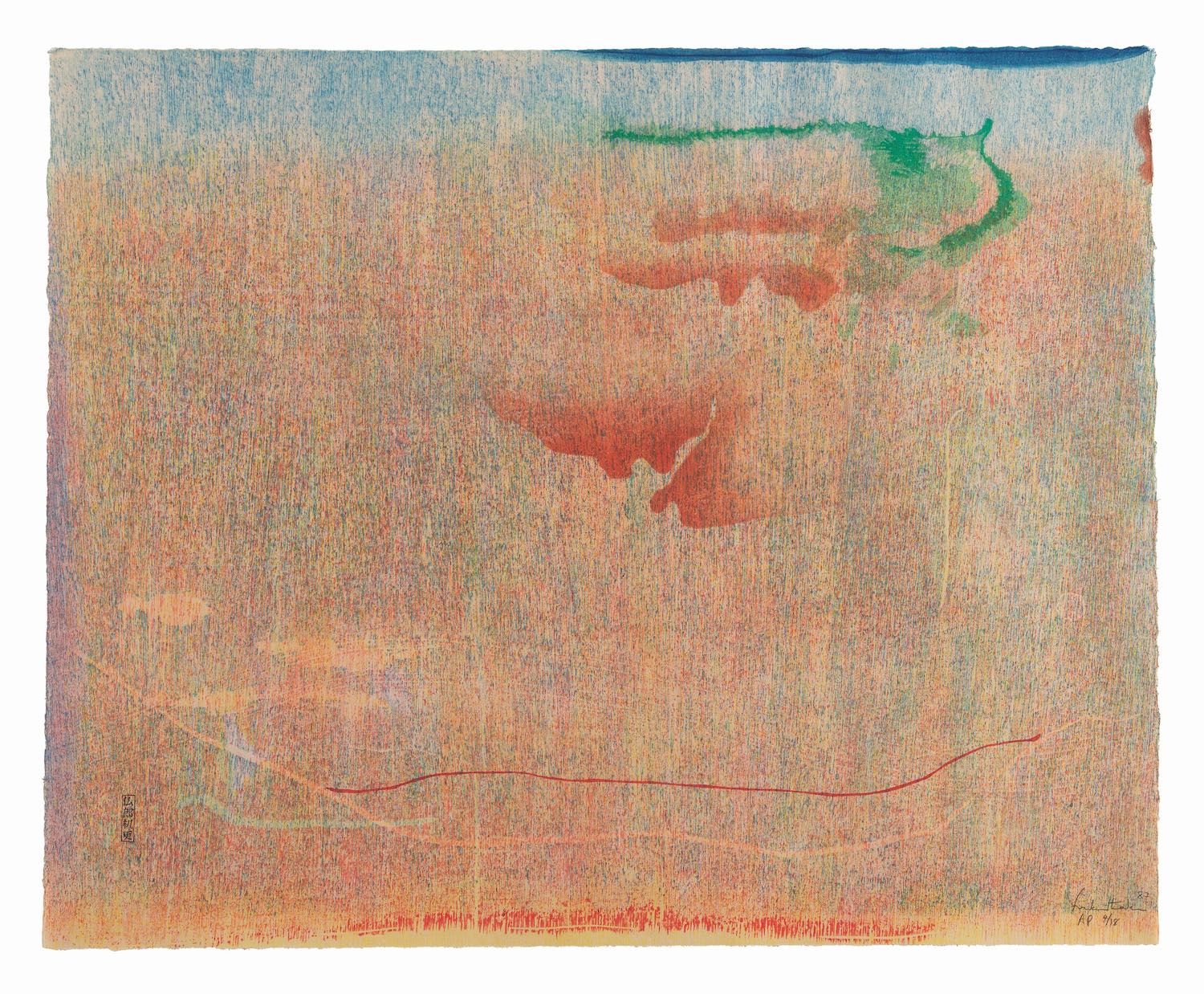

Freefall, 1993 by Helen Frankenthaler. Photograph: © 2021 Helen Frankenthaler Foundation, Inc/ ARS, NY and DACS, London/ Tyler Graphic Ltd, Mount Kisco, NY

Against the back wall in the first gallery is Freefall (1993). This large print of ocean-blue tones moves into darker hues as the piece spreads. In the lower portion of the piece, the green, peach, and yellow shapes see faint darting vertical lines emerge, making the paper look like wood. The works in this first room set the precedent for experiencing how Frankenthaler’s colors move. Guzzying, a delightful word coined by Frankenthaler to describe the technique where she sandpapers and drills into worked surfaces to achieve different effects, allows the colors to continue spreading, and add additional depth.

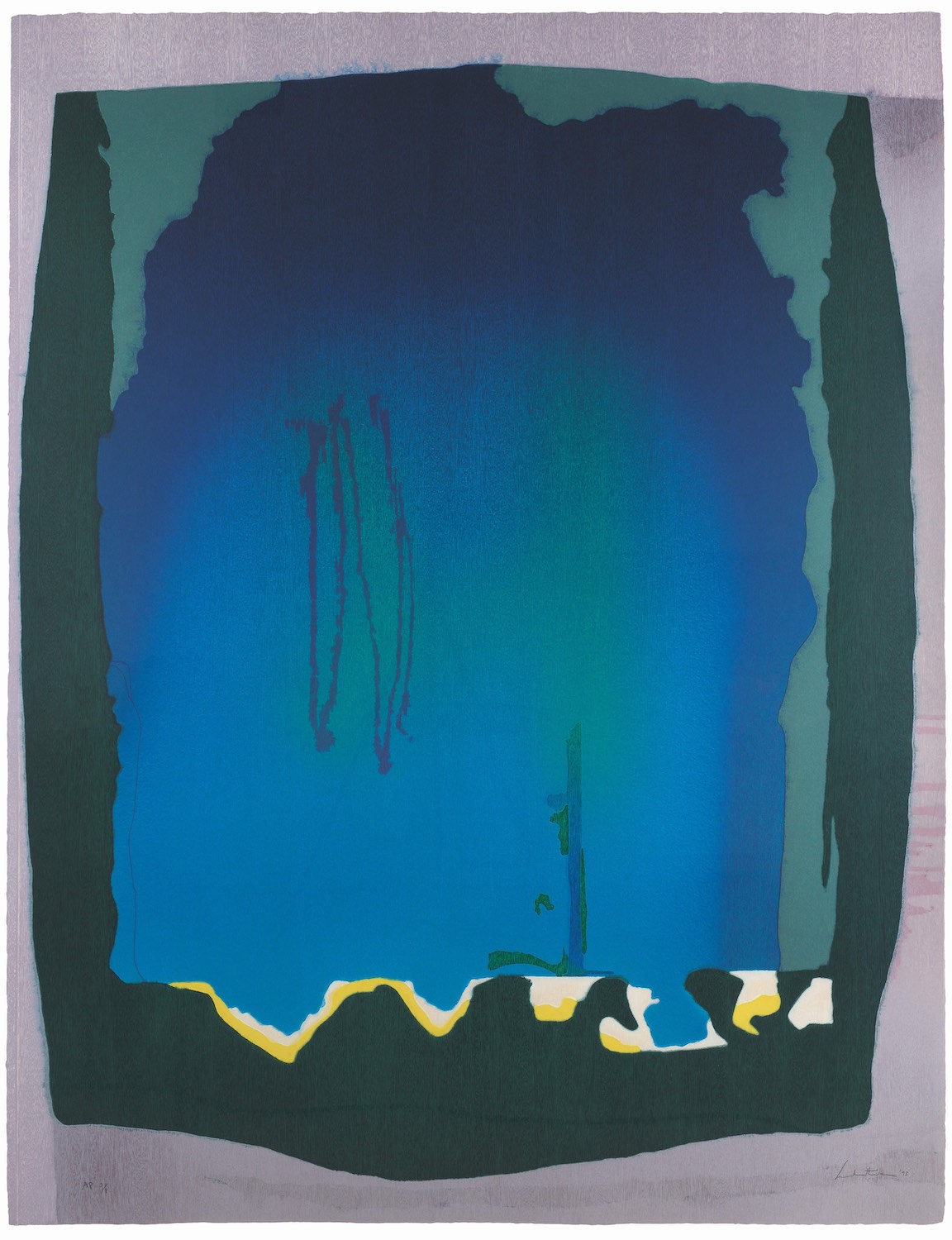

Madame Butterfly, 2000 by Helen Frankenthaler. Photograph: © 2021 Helen Frankenthaler Foundation

Some works feature the soak-stain technique commonly used in Frankenthaler’s painting to thin out paints making them more translucent and abstract. Japanese Maple (2005) sees juicy rich pinks and reds, offset with a full-moon-like blob of electric blue. A triptych composition, Madame Butterfly (2000) made in collaboration with Kenneth Tyler and Yasuyuki Shibata, is a 1 x 2m work where 102 color woodcuts have been made from 46 woodblocks. Frankenthaler cites her prints as being about ambiguity, speaking to these works not imposing an image or experience, but allowing the colors to ignite nondetermined feelings.

Installation Shot, 2021. Photograph: © 2021 Alice Cotterill for Dulwich Picture Gallery

One corridor shows the development stages of prints that formed Essence Mulberry (1977). In this room are some highlights with orange and amber horizontal blocks that are reminiscent of the desert. Frankenthaler says of her woodcut prints: “they’re repeated but they’re different.” The stages of printmaking displayed—along with a video of Frankenthaler at work in her studio—provide insight into the woodblock print process without lengthy curatorial statements distracting the viewer. You are only pulled out of the works with the unavoidable reflection that comes from glass-protected wall pieces being lit up in gallery spaces.

Outside the exhibition sits Frankenthaler’s painting Feather (1979), an iridescent-toned painting contrasted with rich ambers. Shown next to Monet’s Water Lilies and Agapanthus (1923), to highlight both artists’ depictions of the transience of nature through paint, it also remarks on Frankenthaler’s overlooked body of work. “Radical Beauty” is a pleasure for those that don’t perhaps have synesthesia, but want to hear colors and feel colors.

Helen Frankenthaler: Radical Beauty

Until 18 April 2022