It’s difficult to really appreciate the extent to which Anselm Kiefer has transformed the space of White Cube Bermondsey London for his exhibition “Finnegan’s Wake” unless one is familiar with what the gallery looks like under more “normal” circumstances. An absolute epitome of a contemporary white cube gallery, the space is about as pristine, huge and expensive as a gallery can look these days. Kiefer’s exhibition/installation radically alters the space into an apocalyptic chamber of horrors that is also a showcase for his stunningly beautiful paintings. The installation begins in the long hallway that leads to a series of enormous galleries; viewers walk between a long series of metal shelves that contain skeletons, sculptures of tulips, mushrooms and other objects, the format suggesting a medieval mausoleum. Down the hallway, open doors lead to a series of huge rooms containing piles of concrete and metal rubble. Apparently excavated from the artist’s studio complex in France, the debris suggests both the results of war (Kiefer grew up playing in the ruins of post-World War II Germany, which left a permanent mark on his art) and the current environmental crisis. While the broken chunks of concrete and steel rebar create a sculptural statement on the floor akin to the 1970s post-minimalist installations by New York artists, the walls contain towering canvases of radiant beauty.

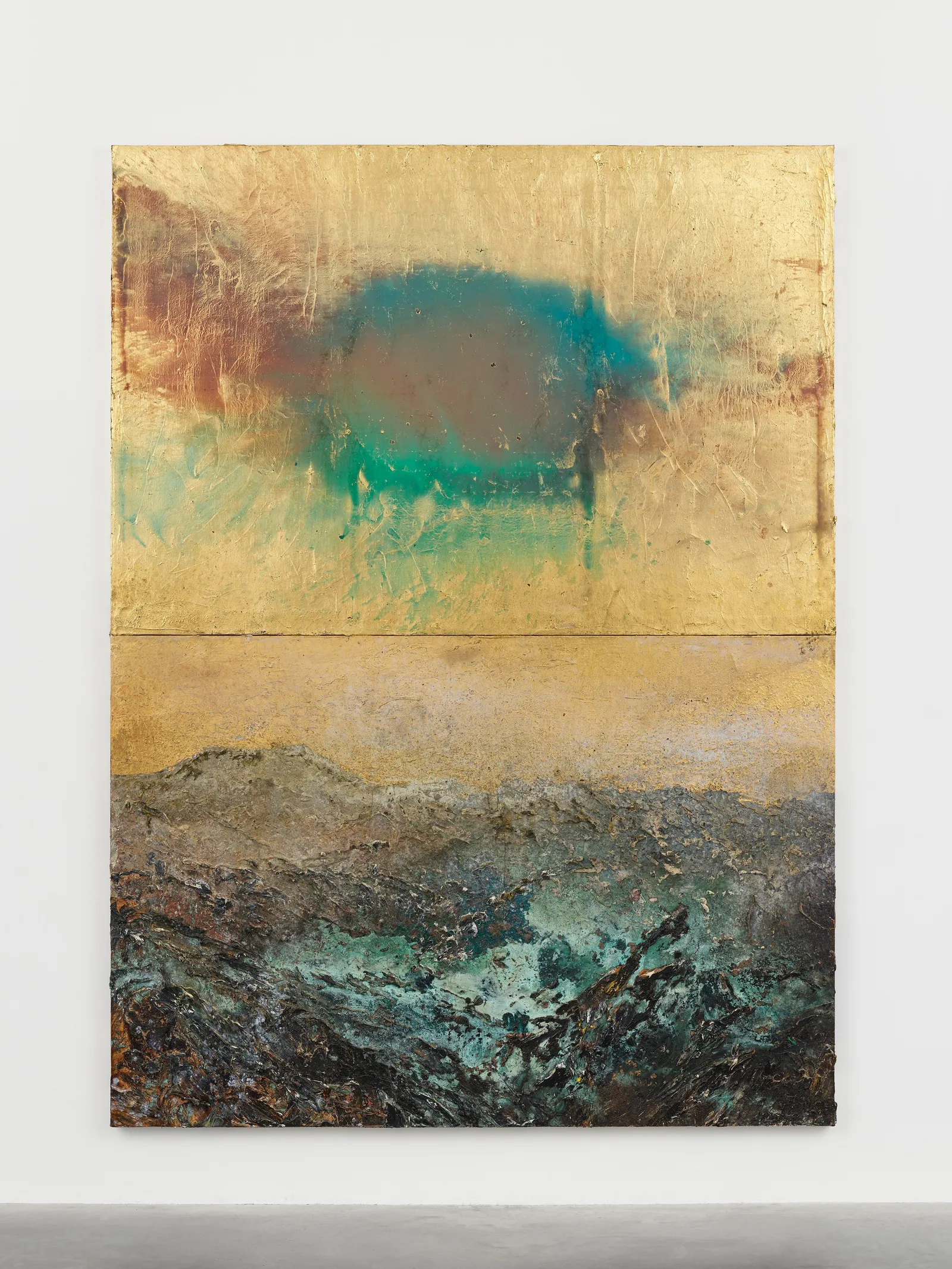

Although Kiefer is the quintessential neo-expressionist whose work, along with an international cadre of other artists, heralded the “return to figuration” in the early 1980s, his paintings have always suggested more of a kinship with American Abstract Expressionism. These works in particular recall the late works of Mark Rothko, whose Seagram Murals reside nearby in Tate Modern, supposedly in perpetuity (they were conspicuously absent during my visit). The Seagram Murals were a big departure for Rothko from his better-known, more abstract works from the 1950s in that they vaguely portray portals, columns and hanging veils within their ostensibly formalist imagery. Kiefer’s new paintings, which have a long list of materials (emulsion, oil, acrylic, shellac, sediment of electrolysis and gold leaf on canvas) similarly appeal through their reductivist formats and relation to color field painting. O nilly, not all, here’s the fust cataraction! (2023), portrays an apparent seascape with a single oblong cloud above it, suggesting not only classic Rothko but the work of his cohort Adolph Gottlieb. Kiefer is only the slightest bit more pictorial than those artists; the magic in his paintings is that they reside in the nether world between abstraction and representation to such a degree that when standing in front of one it seems simultaneously formalist and pictorial.

Kiefer’s art has always been loaded with latent content. A student during the heyday of conceptual art, he has retained conceptualism’s philosophic questioning, which he applied to the grandiose tradition of European painting. The content also has obvious social/political commentary, with allusions to the war in Ukraine, the climate and environmental crises, the holocaust, and other “tragic and timeless” topics that would have appealed to Rothko. In a period in the art world that is dominated by conservative figure painting employing social/political content that often has little to offer aesthetically, Kiefer’s work stands out for its formal power and beauty, relationship to abstraction, and compelling silence that lingers in the viewer long after exiting the show.