In Orkideh Torabi’s caricatures of silly men, comedy and poignancy stealthily overcome the unsuspecting viewer. Midway through this exhibition, one is liable to titter aloud as the portraits’ repetitive simplicity resounds to a starkly touching yet hilarious effect.

Paradoxically, this levity is their subtextual center of gravity. Through her paintings, the Chicago-based Torabi examines male supremacy in her native Iran. By presenting men as laughing stocks, Torabi overturns the pious deference expected of Iranian women towards men, and underscores the absurd lordliness of males whose precious egos are so fragile that a laughing woman is viewed as a grave threat to their dominance.

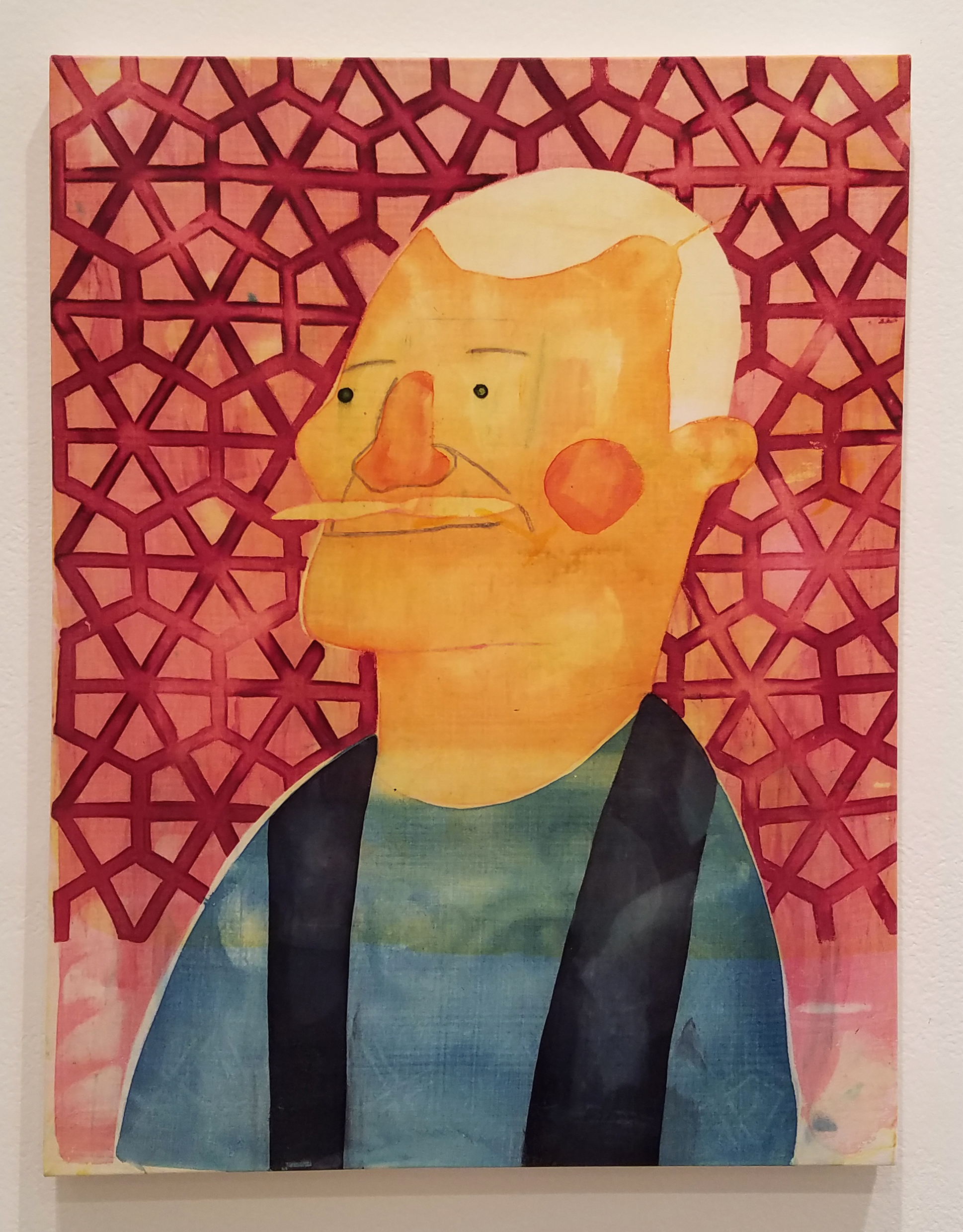

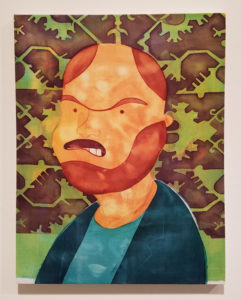

Torabi’s images are silk-screened monotypes, a technique resulting in painterly imperfections that symbolize cultural unevenness and vacillation. Sheer and saturated colors give the cotton canvas a glow resembling stained glass.

Orkideh Torabi, All Toys Are Mine!, 2016 ©Orkideh Torabi, courtesy of the artist and Western Exhibitions, Chicago, IL

Torabi delineates her protagonists in sparse line and wash. Eyes are reduced to button-like dots; teeth are missing; noses are exaggerated or nonexistent; skin tones are unnaturally hued; tacked-on mustaches evoke the childhood game of Pin the Tail on the Donkey. Coxcombical fellows possess feminine features like pursed red lips in Need more focus! (all works 2016). Still others sport eccentric painterly garnishments, like weird fingerprint-shaped growths on the neck and jawline in More coming out.

Intertwined Eastern and Western sensibilities invoke the historic tradition of Persian miniature portraits as much as they recall Honoré Daumier’s trenchantly humorous paintings and busts. Other contemporary Iranian satirists come to mind, most notably Tala Madani, who also employs cutting humor in painterly explorations of masculinity.

All portraits are backdropped by traditional Persian patterns that betoken the men’s empowerment by longstanding cultural tradition. The figure-ground starkness conveys iconic status to the depicted personages, as though they were eminent gentlemen recorded for posterity, which in turn heightens the humor of their ridiculous poses and expressions. Torabi’s modus operandi is the reverse of Kehinde Wiley’s.

Whereas Wiley employs opulent patterns and Old Master painting traditions to confer venerability upon his subjects, Torabi uses traditional prerogatives of portraiture and pattern to parade her subjects’ asininity. The artist imagines herself as director, dictating how the men will be viewed, thus annexing their power.

The title of All Toys are Mine casts its hirsute protagonist as a cocky grimacing juvenile, suggesting that an oppressive society entitles dominants to act as spoiled children. The Protector appears as a leering puppet. A hooked red nose and cherry cheek give the orator in Say it with me the appearance of a rigid doll; however, his declamatory carriage bespeaks self-opinion.

Fellow Iranian artist Shirin Neshat once declared, “Art is our weapon. Culture is a form of resistance.” Torabi’s biculturalism is advantageous; this show would be prohibited in Iran, but her current situation affords her the freedom to explore dark aspects of humanity away from her tyrannical motherland. Despite their stereotypical, cartoonish nature, the magic lies in the fact that they are generic enough to seem familiar, yet specific enough to embody palpable presences. They need not be Iranian, nor even men. Her portraits show the farcicality of haughtiness, and expose foibles and vulnerabilities common to mankind.