The wave of women coming forward with accounts of sexual harassment and assault has swept the art world like the Santa Ana winds in a California brush fire, and all I have to say is “Finally.” Historically, women have served as objects of sexual desire within the context of art, and a blind eye has been turned to their exploitation by powerful men. Still, just because women are coming forth with their stories doesn’t mean that the art community has been particularly receptive. An anticlimactically lackluster response has led me to question: Is the art world sweeping #meetoo under the rug?

Knight Landesman

When Knight Landesman, former publisher and current co-owner of Artforum, was accused of sexual harassment this past October by staffer Amanda Schmitt (among others), an open letter titled “We Are Not Surprised” was published on the internet and signed by over 1,800 people. The open letter called for the resignation of Landesman, which was fulfilled in that he was fired from his publishing position. As to his removal from co-owner, there has been no progress. And as a shareholder he continues to benefit from Artforum’s new “intersectional feminist” point of view.

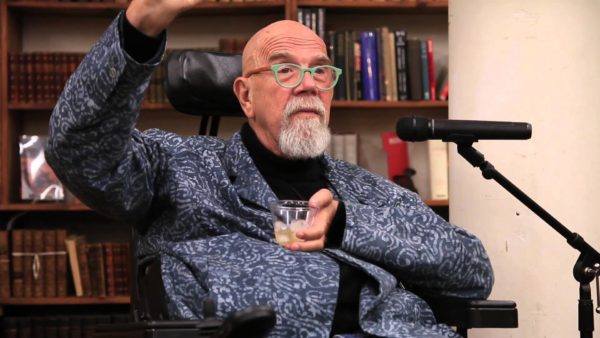

This scandal was bookended by accusations against portrait painter Chuck Close, when he was accused of sexually harassing two women. In response to the accusations, Close gave a half-hearted response, saying “I am truly sorry, I didn’t mean to. I acknowledge having a dirty mouth, but we’re all adults.” While some museums have chosen to postpone exhibitions by Close in solidarity with his accusers, others, such as MoMA and the Met, continue to show his work.

Chuck Close

This question of whether or not to show Close’s work at museums begs the greater question that many people in the art world seem to be grappling with, which is how do we separate the artist from their art, and should we do so at all. In historical terms, if we were to remove all works by men who exploited, harassed and assaulted women, most of our museums would be half-empty, and there most certainly wouldn’t be any Picassos on view. (Picasso allegedly physically abused women, beat them into unconsciousness, burned them with cigarettes, and leveraged his power to sexually take advantage of models.)

On one hand, it would be interesting to imagine every museum removing all instances of sexism and works by sexual abusers in their halls. It’s a revolutionary idea—and if these institutions removed all of these works, it would provide space for minorities and women that have been denied for so long. Imagine: every piece of art by an abuser in a museum replaced by a work created by a woman artist. While this solution may be considered radical, it is no less radical than continuing to honor work by abusive men.

Giovanni da Bologna, Rape of the Sabine Women, 1583.

On the other hand, many curators and artists believe that the work should remain intact despite the artist’s wrongdoings. Something I hear often, even by forward-thinking women in the art world, is the fear of creating an environment in which artists are scared of saying something that is offensive and where everyone must behave according to some prevailing cultural code. While I agree that censorship has typically acted against, not in favor of, the creation of art, the “free speech” of some, oftentimes means the silence of others. Take, for instance, established male artists who think it is appropriate to tell emerging female artists that they are “pretty little painters,” or gallery owners who tell female artists that they can “work their way in… if you know what I mean,” or male professors who tell female students “you should paint nude self-portraits because that’s the most interesting thing you could create”—all of these, by the way, have happened to myself and close friends. When men wield their power under the guise of “free speech” and “talking like adults” it often leads to an inadvertent censorship of female artist.

If museums and galleries insist on carrying artists who have historically been abusers, like Picasso and Close, there must at least be a caveat to contextualize their work. Sexually suggestive works of underage “muses,” nude paintings of women by known abusers, and works evoking a lack of sexual consent should not be exhibited without accompanying descriptions of their painter’s and society’s wrongdoings. Still, this feels like an inadequate reaction. As long as owners and curators of museums and galleries remain largely male, there should—and will—continue to be a fight for not only more female representation, but also for radical art and action for the rights of women.