If one wanted to be very art historical about it, Math Bass’ work resembles Gustave Caillebotte’s The Floor Scrapers (1875) with its beautiful detritus and bones and dust and longing bodies and skin-as-paint-as-floor and new life emerging from every crevice. The predecessor for both Bass and Caillebotte might be the darkly excessive and comical “unswept floor” mosaics by the Ancients, paintings of castaway fruit and bones to prove that you were rich enough to eat heartily. Yet the art historical always seems smug, paranoid, dissecting and penetrating in a non-consensual way. Art history relies on reductive biomorphism and it relies on an identity politics that has no room to dream, no lustful orifices that spew forth heretofore unimagined, tentacled shapes. Art history aims to fill all holes when those holes might prefer to remain agape or to be filled only with fluids and gasses. Art history hates bottoms.

One night, late one night, late, before dreaming, Math and I talked about Twin Peaks: The Return on the phone. We were both sad and queer that night, I think, queer and sad, queerly sad and sadly queer. For good reason and for reasons unknown, queers get sad pretty easily. I always think of Math now when I cruise through the curves and bumps of Mulholland Drive (the street) or Mulholland Drive (the film). My interactions with Bass always remind me that art is a necessary and reckless and activist and nostalgic and reclusive and spectacular and blithe and mysterious and denuded state of free association through the hills and valleys, lit only at times by brake lights and far-off lighthouses and swiftly tilting planets.

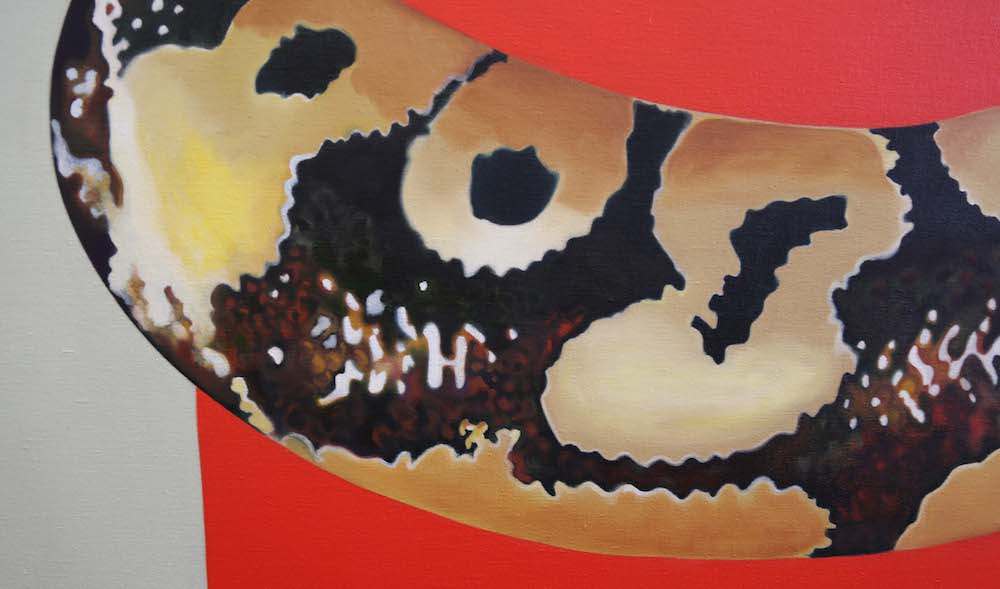

“Snakeskin Ring” (detail), 2021, Courtesy of the artist and Vielmetter Los Angeles

On that night, I told Math that they needed to watch episode eight of Twin Peaks: The Return, which features a monster in the form of a lumberjack or logger or some other manly profession. The monster always has a cigarette in his mouth and, before he crushes your skull, fists you even, he asks menacingly, “Got a light?” That there is an iconographic association here in that Math’s paintings sometimes involve smoke and cigarettes (and that every queer in LA, myself included, is air-quotes “quitting smoking”) is less important than the fact that with each cigarette, with each request for a light, there is still more detritus, still more floors to be swept by beautiful monochromatic housewives. Ash is blown into the wind or accidentally mashed onto a finger or intentionally driven into flesh. The butts that once housed said ash are wet and dry and featureless and painted like whores. The environmental toll these castaways have notwithstanding, we could more optimistically understand them as traces, as markers of touch or closeness or distance, as the paused, disintegrating frame between life and death.

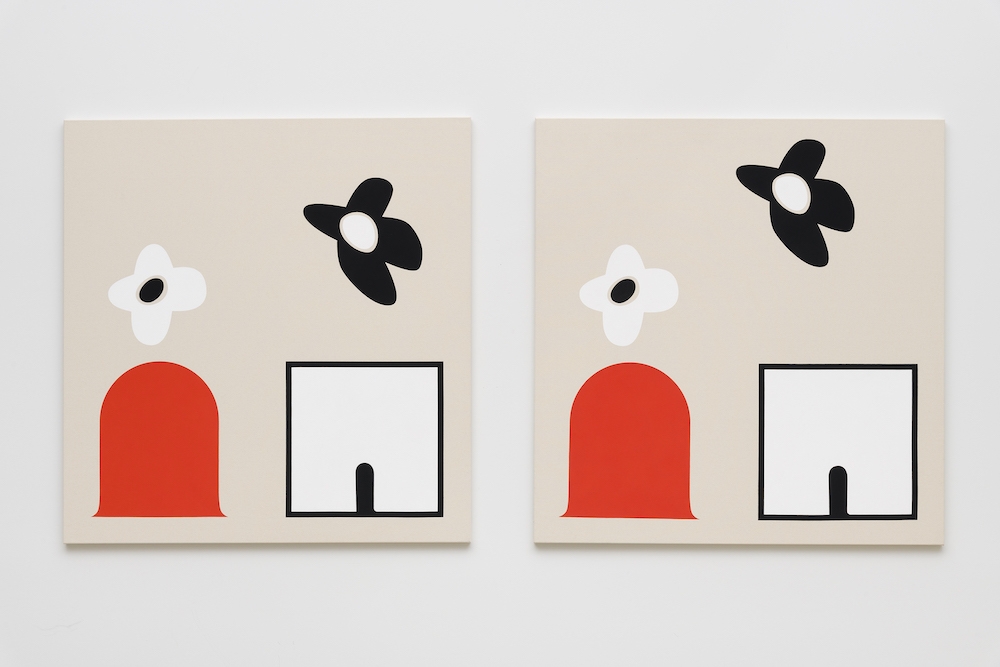

“Not Yet Titled” (detail), 2020, Courtesy of the artist and Vielmetter Los Angeles

The trace and its concomitant longing are indicators of proximity. The smoking man in Twin Peaks: The Return begins far away. He infects the nondescript town via radio signals. Then he comes closer, as a monstrous amphibian that enters the mouth of an All-American girl while she sleeps. Sweeping may indeed be a part of her chores, and who knows if that will get done in the morning? It is a quaint rape like so many others we have seen before onscreen or on canvas. The smoking man’s desire for a cigarette is not just a non sequitur or a way to convince others that he is just a normal guy. It is an earnest need for connection (nobody does manage to produce that archetypal light, and that must be so sad). It is also a means of further spreading the leftovers, the ash of whatever evil drives him, burns him. Sympathy for monsters is a passé hallmark of modernism, yet it remains the quintessential way to relieve ourselves from the fear of being fundamentally anti-relational, or even evil.

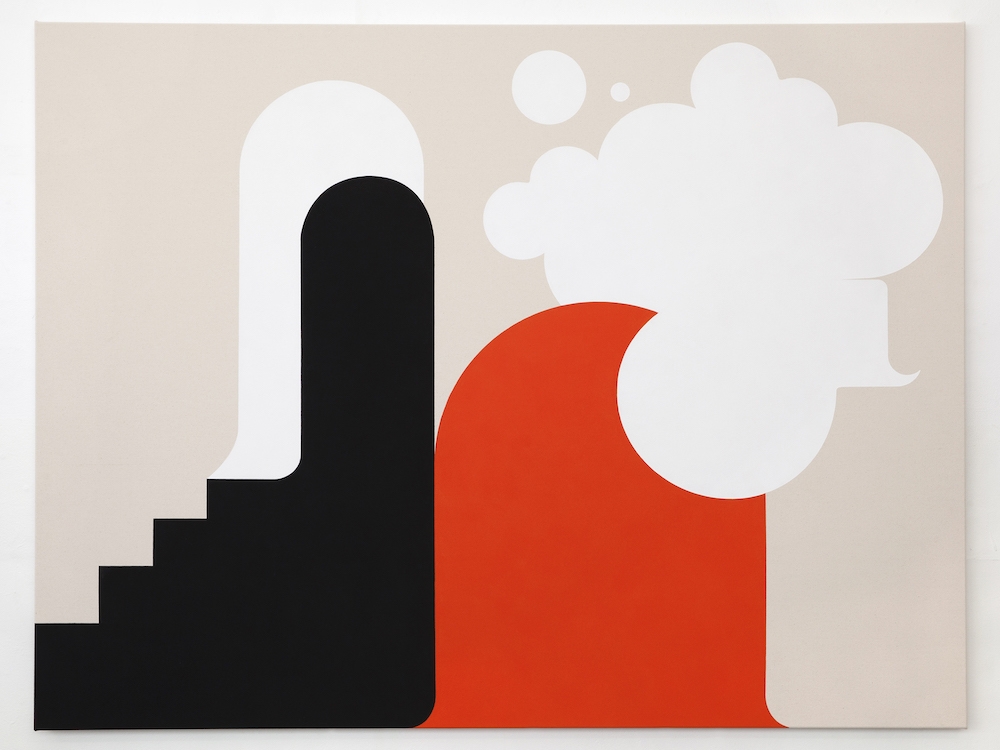

“Newz!,” 2019, Courtesy of the artist and Vielmetter Los Angeles

Yet sympathy or empathy for the destructive thing or body are not the same as proximity. In Lars von Trier’s Melancholia, the impending end of mankind (via the ultimate end of proximity—the apocalyptic disintegration of Earth itself) is a source of fear for some and the only source of life for others. Surrounded by Richard Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde, Earth and Melancholia swing past each other and loop back, getting closer and closer, just like the erotic anti-climax of the “Liebestod,”which throbs and throbs frustratingly until the very last second, until the very last drop of pigment or fascist cum. As Leo Bersani argues, the planets in Melancholia, not unlike Bass’ similarly cosmic Wizard-of-Oz-tornado of creatures and objects, become metaphors for the receptivity constantly being negotiated in the psychosexual sphere. What he means to say, I think, is that we are all, even the earth itself, bottoms at heart. We long to be the eye/hole of the storm, to be inside the cyclical conclusion of “Liebestod” or to take the vengeful and kind planet inside us so that we might expand to the point of exploding and producing a cloud of smoke, or we take our phallic cigarettes and ask that they be lit so that we might take pleasure in watching the flame engulf them, because we wish to do the engulfing; to be the generative void that pleasurably gobbles up everything, crushes things, creates fissures, bleeds, and places unexpected things next to each other or inside each other.

Math Bass, photo by Steven Taylor, 2019

A strained, stretched, widening, loosened metaphor, one that gives lights and receives them, might be the best way to describe Math Bass’ work. Yet metaphor is an easy interpretational mode that relies too heavily on iconography. Morever, description logo-centrically implies that all that is felt can be written or painted, that you actually can describe what bottoming is like to someone who has yet to do it. A simile might be better. In this moment, it seems more capacious. Bass’ work is like a ride on the Long Island Rail Road, winding through a certain kind of world, in which crushed skulls and young love happen simultaneously and often unnoticed, where aspiration and reality meet, where the Piano Man’s jar is filled up with cock-like bread, where hearts are broken and lose their three-dimensionality, only to unflatten at the sight of beautiful arms at work on a floor. And then, eventually, you reach the lighthouse, where the water crashes up against the shore, and there you lie, naked, hoping the droning illumination will project you into yet another narrow strip of land filled with memories.