When Hannah Black wrote in her open letter to the Whitney Biennial curators “it is not acceptable for a white person to transmute Black suffering into profit and fun, though the practice has been normalized for a long time,” she did more than bolster a national debate about ownership of black pain, she connected with Denver artist Taylor Balkissoon and her frustration with her work mediated by a white audience. A biracial, queer, female artist, Balkissoon grapples with the commodification of black identity in the exhibition “Now More Than Always.” For one-night only, Balkissoon commandeered and curated the apartment of Adam Gildar, the owner of Gildar Gallery, situated just upstairs from Balkissoon’s group exhibition. The result is a jarring confrontation with the privileged privacy a white male gallerist is afforded against the cultural obligations placed on her.

Bedroom of Adam Gildar, the owner of Gildar Gallery

The living room is filled with white balloons, drawn with cartoonish staring faces. A musical rotation of Kanye West, Destiny’s Child and Etta James plays loudly as a projector flashes images of the respective artists. A Djembe drum hangs high on a wall opposite of a tennis racket. In the bedroom, a bed is covered with a fluffy royal blue comforter in a pattern of Ringling Brothers-style clown faces. Some of the clown faces have been painted black with silver oval marks for eyes. On the nightstand, the book White by Richard Dyer is carefully placed next to an antebellum porcelain figurine. The white swirling ruffles of her dress have been broken from the body and rest next her. The blonde figurine’s hands and face have been altered in black paint. The bedroom wall hosts a slide show of what look like vacation photos. Was that Niagara Falls or Victoria Falls that I just saw? Is this Balkissoon’s apartment or Gildar’s? Is there a different expectation about their respective homes?

Detail of the nightstand in Gildar’s bedroom installation

It’s disturbing to wander through someone’s home in their absence; judging every possession as a reflection of the life that resides there. Similarly, it is uncomfortably easy to reduce the complicated subject of identity and representation in art to a single object. The art world craves such conversations with underrepresented black artists. Maybe it is out of a desire to learn and adjust or out of spectacle. According to Zadie Smith in her essay “Getting In and Out,” “to be oppressed is not so much to be hated as obscenely loved. Disgust and passion are intertwined.”

Khalil-Cezanne-Zawadi in foreground; Sadie Barnette on wall behind

Detail of How much you got on my 40 (2017) by Kahlil Cezanne Zawadi

Taylor Balkissoon, Mercy, 2017

A triangular sculpture made of cement-filled malt liquor bottles titled How much you got on my 40 (2017) by Kahlil Cezanne Zawadi, tempts the gallery visitor to talk about class and race in all the predictable ways. With a wink at the collector, the artwork’s material list includes “power grab.” Balkissoon’s Mercy (2017) is a broken windshield bejeweled and wrapped in necklace chains. It could be a trauma aestheticized or it could address something less ambiguous like her surrendered car after thousands of dollars of parking tickets. There is a quality of emotional withholding in the group show of nine artists which completes Balkissoon’s experiment; that her experiences shape her artwork but experience cannot be owned by someone else. Any perceived intimacy with the artists’ motivations are just that, problematic perception.

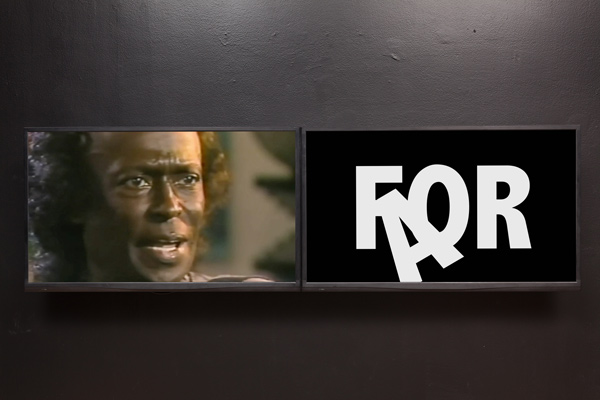

Jibade-Khalil Huffman, Duets, 2017

Jibade-Khalil Huffman’s video artwork, Duets includes a clip of Miles Davis from a 1988 interview on 60 Minutes where Davis says he would play if no one listened because he loves music. When people are listening, and buying, the art becomes a dialog even if the artist speaks no words. But sometimes they are not having the same conversation.

Photos courtesy Kealey Boyd & Gildar Gallery in Denver, CO

0 Comments