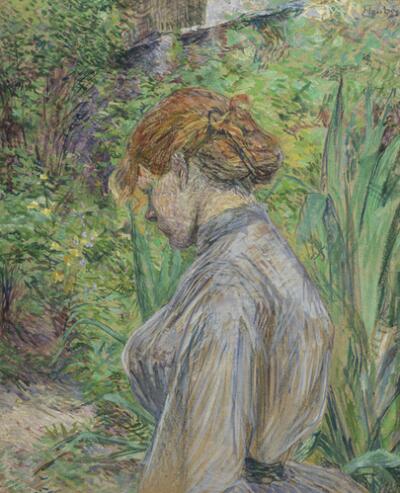

Upon exiting the newest exhibition at the Norton Simon Museum, “By Day and By Night: Paris in the Belle Époque,” each visitor is invited to take a print of Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec’s Red-Headed Woman in the Garden of M. Foret. This print is especially fitting as a souvenir, since Toulouse-Lautrec’s work is displayed prominently throughout the exhibit, and even those not done by Toulouse-Lautrec feature a similar subject matter: women. In Red-Headed Woman, the titular figure is seen from behind, looking down, in a tumultuous, sketchy arrangement of leaves and branches. Shadows cast strongly across her face, and I was left to wonder what it is she’s thinking about, only to be stopped from understanding by her averted gaze. Depictions of women both in moments of rest and work are featured across the collection exhibited, as the history of the art of the belle époque can be read as a history of women.

“Red-Headed Woman in the Garden of M. Foret,” (1887) by Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec. Oil on cardboard, 28-1/8 x 22-7/8 in. Courtesy of The Norton Simon Foundation.

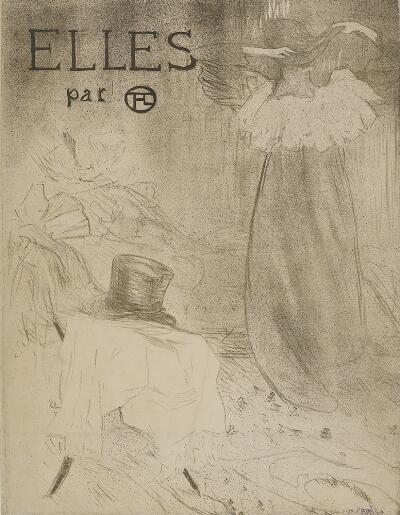

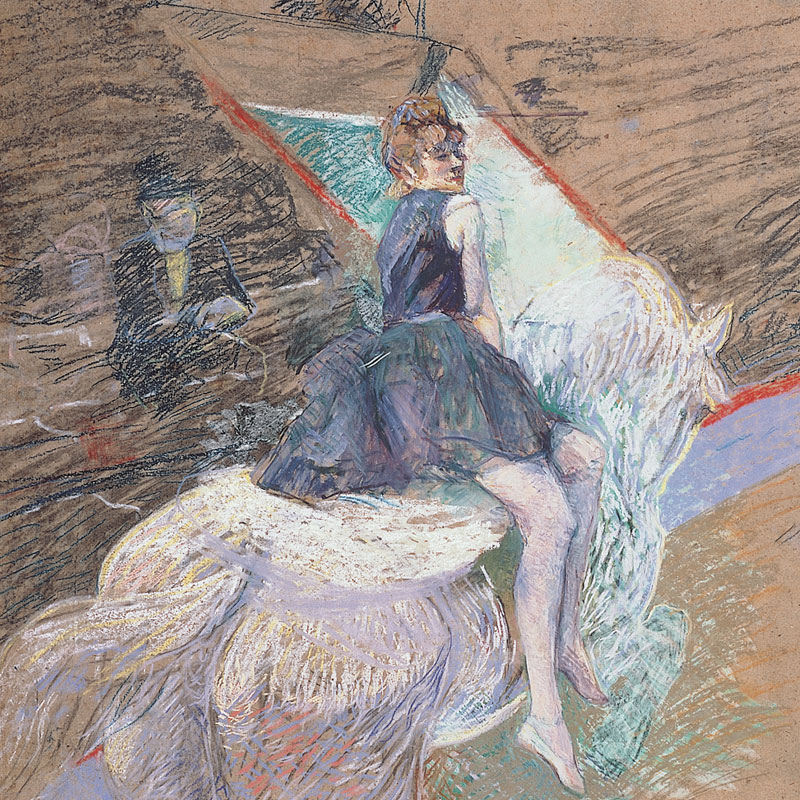

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec’s lithograph magazine Elles illustrates this focus on women as emblematic of the history of the belle époque. This magazine – whose title translates French to a feminine they, highlighting the “otherness” of women in Toulouse-Lautrec (i.e. those women) – features chromolithographs of women in various parts of life, from lazing sleepily in bed and getting dressed to sitting confidently on theater steps and preparing baths, even possibly in lesbian relationships. These prints don’t attempt to idealize the figures as paintings in the past would have done, and instead show real women in everyday life, exemplifying the progressive nature of Toulouse-Lautrec’s work. But aside from the one print of Madame Cha-u-ka-o, the scenes do not vary greatly, and none in Elles show women at work. In fact, the vast majority of paintings and prints in the exhibition show the women of the belle époque as either terribly bored or as poor laborers or dancers, highlighting the distinct lack of opportunity for women during this era.

“Elles” cover, (1887, by Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec. Color lithograph, 20-1/2 x 15-3/4 in. Courtesy of The Norton Simon Foundation.

But it isn’t just the art that is shown that demonstrates the lack of opportunity, it’s the art that is not: the work of women artists. The absence of women as artists is a well-documented history of inequity, explored directly by critics like Linda Nochlin nearly a hundred years after the belle époque, and also by Impressionists like Marie Bashkirtseff. Bashkirtseff addresses this unfair treatment in her journals, lamenting that a woman who “walks about alone commits an imprudence,” and desiring to be “as free as a man.” Bashkirtseff would never see a day where that was a reality for her, and today we are left with a history half-told: an understanding of life — life of women, of men, of Paris — told by men like Henri Toulouse-Lautrec, Edgar Degas, and Pierre Bonnard. “By Day and By Night: Paris in the Belle Époque” shows a history of women told by men, as they (sadly for us) were the only ones who were able to document it.

By Day and By Night: Paris in the Belle Époque

Norton Simon through March 2, 2020

0 Comments