“Nonmemory,” for the artist Mike Kelley, was something akin to his notorious usage of the “uncanny,” a theory borrowed from Freud wherein repressed memories emerge into disturbing feelings. In nonmemory, however, what has been forgotten stays so, and recollection is built around, or in the stead of, that which has been lost. Probing its eponymous concept, this group show features Kelley’s work alongside that of seven other contemporary artists—Kelly Akashi, Meriem Bennani, Beatriz Cortez, Raúl de Nieves, Olivia Erlanger, Lauren Halsey and Max Hooper Schneider—and exposes the modes in which Kelley’s themes have snaked their way through art’s advancing discourse.

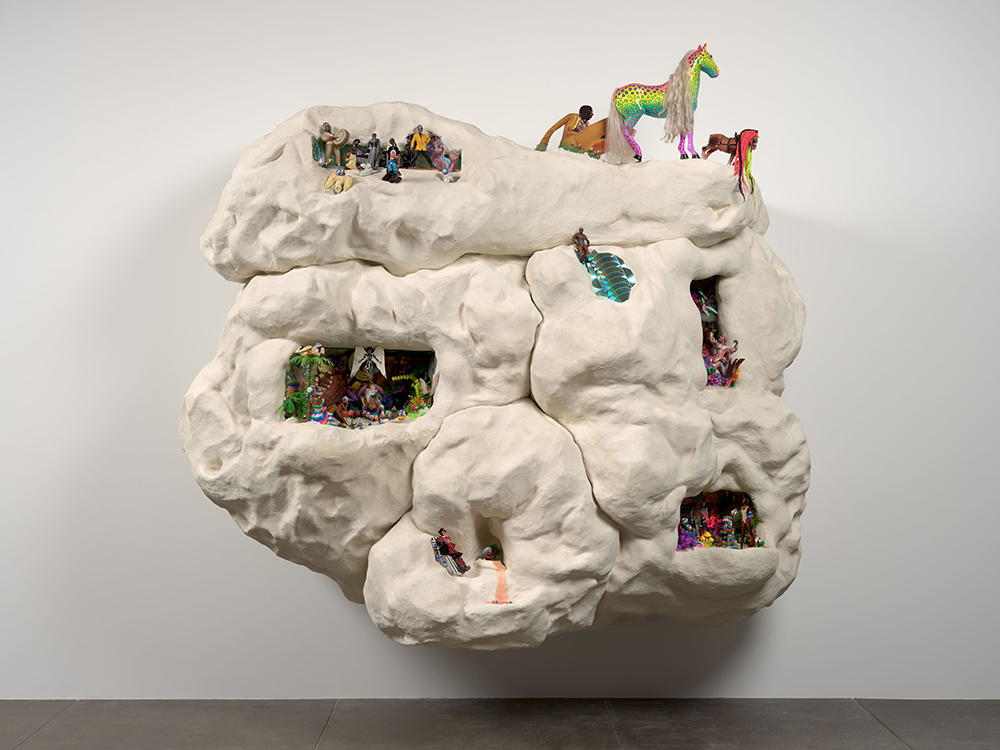

Setting the tone for the show is Kelley’s Mobile Homestead Swag Lamp Edition (2010–13). Modeled after Kelley’s childhood home, this sculpture ties in with his nearby video works, both of which depict portions of Kelley’s only public art project: a full-scale replica of the home dedicated for com- munity use in Detroit. “Cubbyhole architecture,” referring to the nooks and crannies of a home or school, is one site of Kelley’s nonmemory—the forgotten places that might be synonymous with abuse. In the three works grouped here, Kelley makes private space public in a gesture of rectification. On the opposing wall to Kelley’s videos is Lauren Halsey’s dat fuss wuz us (2023)—a bulbous cloud of a wall- mounted relief, the sculpture carries a multitude of Black figurines and Technicolor objects in its caverns. Dat fuss wuz us activates hyperbolized, confined space while resembling an architectural model—leaving the viewer with a similar resolution to Kelley’s in this context.

The works in the next room are very much stylistically in sync with Kelley’s “Kandor” series, wherein the artist fixated on the tiny city kept in a bell jar in Superman’s lair. “I wonder if [he] ever feels the desire to smash this city and finally live in the present,” Kelley said of this series. Across from Kelley’s Kandor 16 (2011), a glowing glass city perched on a rock plinth, is Kelly Akashi’s Cultivator Cavern (Thorned Truss) (2022–23). A perfect bell jar cut into marble, one imagines that the secrets it contains would be much harder to smash—the past it might indicate more difficult to be rid of.

Lauren Halsey, dat fuss wuz us, 2023. Photo: Keith Lubow. Courtesy of the artist and Hauser & Wirth.

The next room is clearly curated around Kelley’s “Memory Ware” series. Raúl de Nieves’ One One Eight Four Five Time Is On My Side (2023) is an incredibly intricate tiling of beads, toys, chains, dolls and more connected to a circular panel, imbuing the work’s surface with an accumulation of signifiers—each item indicating its own history of previously independent objecthood. Next to one another, the de Nieves and Kelley works reveal an undeniable likeness, thus creating another layer of uncanny resemblance in situ.

Finally, one passes by Meriem Bennani’s space shuttle–like video installation Ponytail (2019), otherworldly works by Olivia Erlanger, such as 16.5918° S, 39.1028° W (2023), which depicts a planet shot down with an arrow, and Kelley’s Repressed Spatial Relationships Rendered as Fluid #1: Martian School (Work Site) (2002), an architectural model-like mobile of the McMartin preschool and its floor plan. These final notes of the exhibition drive home Kelley’s interest in the idea that what one can’t remember might be actively repressed. In the uncanny, this repressed memory could return as something beyond comprehension—or, if applying Kelley’s sense of humor, extraterrestrial. In terms of both style and subject matter, the artists showing alongside Kelley in “Nonmemory” verge on appropriation with their work, often bearing such a strong resemblance to or resonance with their predecessor. As an appropriator himself, Kelley would likely endorse the gesture.