By way of a smallish retrospective at the New Museum titled “Al-ugh-ories,” and a major exhibition of new paintings at Anton Kern Gallery “Magnificent Delusion,” Nicole Eisenman has lately given New York audiences a lot to look at. One of the intriguing things about her paintings is that their anecdotal specificity opens up the interpretive possibilities, rather than delimiting them. Whether we’re looking at a portrait of a single subject or a street scene bustling with dozens of figures, we think we might know roughly what’s going on, but our doubts provoke keen pleasure. Some paintings might seem to be more straightforward than others—but given Eisenman’s gift for innuendo and intrigue, it’s hard to be sure. Just when you think you have a painting pretty much worked out, something throws you off. It resists definitive interpretation.

Installation view, “Nicole Eisenman: Al-ugh-ories,” 2016, courtesy New Museum, New York, photo: Maris Hutchinson/EPW Studio.

In fact, “interpretation” is an inadequate term for the kind of engagement Eisenman’s work demands. You become involved with these paintings, as you might with a novel or a film. At a public talk at the New Museum in May, exhibition curator Massimiliano Gioni asked Eisenman if the emotional bleakness of her allegories of contemporary life and art-making was accurate. Her reply: “Nobody becomes an artist because they’re happy.” She discussed at length something that painters usually don’t—at least, not publicly—though it is a common occurrence. She noted that often, over a protracted period of working on a painting, her understanding of what motivates the painting shifts, becomes refocused, and also more expansive: “Painting something gives you time to meditate on the thing you are painting.”

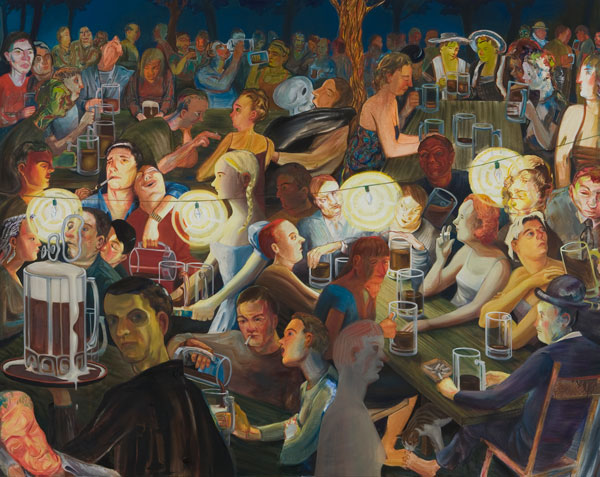

Biergarten at Night, 2007, collection Bobbi and Stephen Rosenthal, New York, courtesy the artist and Susanne Vielmetter Los Angeles Projects.

Biergarten at Night (2007) is one such painting, and an example of the crowd scenes Eisenman orchestrates with tremendous aplomb. In the weak light of dangling bulbs or lurking in the shadows, everyone is drinking, “pushing back against the edges of despair” as best they can: a smoker blows concentric rings at her date; some guy is mansplaining something to his companion; several others seem lost in thought. A waiter moving through the left foreground assesses the viewer with a sharp glance, but a greater surprise is to make eye contact with a thuggish character in the midst of the crowd, whose head smolders in shades of red. The waiter is straight out of central casting, but the thug is a demon from a nasty dream.

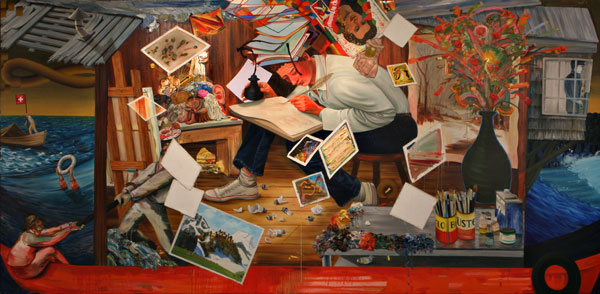

Nicole Eisenman, Progress Real and Imagined, panel 1, 2006, (detail)

At the New Museum, Eisenman took issue with the suggestion that her work contributes to a supposed resurgence in the viability of painting as a medium, saying, “I didn’t feel I was taking a stand about a ‘return to painting’ because I never understood painting as a thing that went away.” The appeal of the medium is that “you look at it and see what’s there—nothing is hidden from view.” An epic self-portrait in a studio/ship on the open sea, Progress: Real and Imagined (2006) depicts the painter’s task as integrating her talents and her tastes, the history of her medium, and the culture in which she functions. Though Eisenman avails herself of the language of painting, her attitude toward art history is that of scavenger, not a scholar; she said, “I have very particular needs from art and I seek to have those needs met by looking.”

Apparently she needed a representation of a victimized woman for Spring Fling (1996), the earliest painting in “Al-ugh-ories,” in which a helpless maiden, tethered to a rickety trellis, attempts to strew flower petals from a satchel. The figure is lifted from Ingres’ Ruggiero Freeing Angelica, a rather melodramatic 1819 canvas in which Cetus, the sea monster, is deprived of a nice lunch, and promptly dispatched. (The narrative theme, known also as Perseus Freeing Andromeda, is likely the source of Renaissance tales of princesses, dragons and knights in shining armor.) Of course, that meeting was no fling; the couple had nine children and became the ancestors of the Persians. But does their story inflect the meaning of Spring Fling? Does it matter that Andromeda means “ruler of men?” Or was Ingres’ Angelica selected simply for her over-the-top pathos?

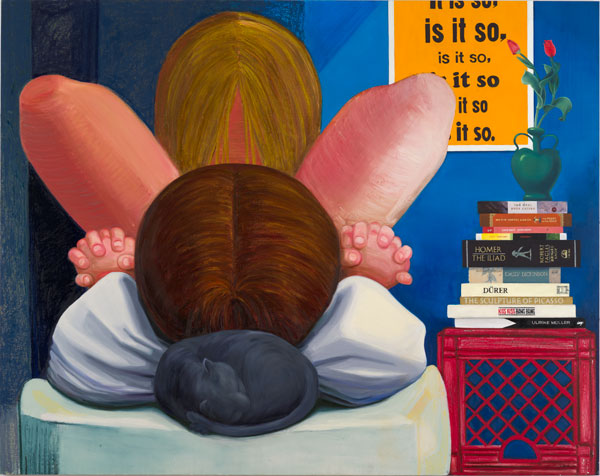

Is it so, 2014, courtesy of the artist and Susanne Vielmetter Los Angeles Projects

Regarding the extent of her responsibility to be political, Eisenman cited her role in the controversial 2014 version of Manifesta, the European biennial of contemporary art, which took place at the conservative Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg. In the context of Russia’s then-new anti-gay laws, the exhibition’s curator, Kasper König, selected Eisenman’s It Is So (2014), which depicts, indirectly but unmistakably, two women having sex. “My point of view is not represented enough and that drives me,” Eisenman told Gioni. It Is So contributed to the furor surrounding Manifesta, “but only because of the state of the world. It’s their problem, not mine… I wanted to see my desire more explicitly in art history.”

The Triumph Of Poverty, 2009

Yet she does not shun topicality. A brown swarm of beautifully painted rats anchors The Triumph of Poverty (2009), in which a motley procession of the dispossessed and downtrodden makes its way through a leafy middle-class suburb. Prominent among the paupers are Oliver Twist (looking very Jackie Coogan—an actor whose childhood earnings were squandered by his parents), Tom Joad from John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath (maybe), and a tall, blind man whose anatomy is literally ass-backward. Along the bottom of the picture, on a tiny scale and in reverse, is the sequence of tumbling figures in the Elder Bruegel’s 1568 painting of The Blind Leading the Blind. This quotation grounds the otherwise surreal tableau in the aftermath of the 2008 subprime mortgage debacle with its mushrooming real estate foreclosures.

In nearly every crowd scene, there is one astounding figure around whom—once you see it—the entire painting revolves. Eisenman, who describes herself as a “storyteller,” took the title of Beasley Street (2007) from a ballad of class conflict by the British punk poet John Cooper Clarke. In the middle distance of this well-populated painting, a man in a black suit carrying a briefcase and umbrella, reaches the top of a set of steps while scowling over his shoulder at a panhandler. Other relationships are more veiled or ambiguous, but they are framed by this caustic gesture of contempt for the unfortunate.

Another Green World, 2015, oil on canvas, 128 x 106 inches, courtesy the artist and Anton Kern Gallery, New York.

The standout of “Magnificent Delusion,” Eisenman’s solo at Anton Kern, was Another Green World (2015), which is over 10-feet high. Reminiscent of Max Beckmann’s scenes of the Weimar demi-monde, the painting depicts a crowded apartment where 30 or so partygoers interact, or isolate themselves: a small group shares a joint while intensely conversing; a couple get drowsily lost in each others arms; the exquisitely painted central figure—a beautiful woman momentarily forgetting her face—becomes distracted by the back cover of the eponymous Eno album. A man tries to enter through a door on the right, and the viewer identifies with the newcomer’s momentary disorientation.

The painting contains moments of risk but it is not, overall, a risky painting. Eisenman flirts with pastiche by sampling a range of representational styles, including those found in illustration and comics. She flaunts a kitschy, moon-over-Manhattan background. She seems also to be playing with the obvious symbolism of a shimmering disco ball, and an enormous sausage being dismembered. (Hilariously, a cartoon-style cobweb indicates that the person whose legs protrude from under a pile of overcoats has been immobile for some time.) A viewer might admire the artist’s strategy of hedging her more questionable pictorial bets within an inarguably impressive canvas, and at the same time wonder when Eisenman will fully embrace the irrational and really stop making sense.