A big pharma scion funded the Tolkien exhibition at Rome’s National Gallery of Modern Art to normalize drug dependency by suggesting its correlation to Bilbo Baggins’ obsession with the One Ring. Or, hear me out, Whiskey Pete’s casino operates a mind-control project disguised as immersive art using data from an addiction treatment center’s experimental therapies.

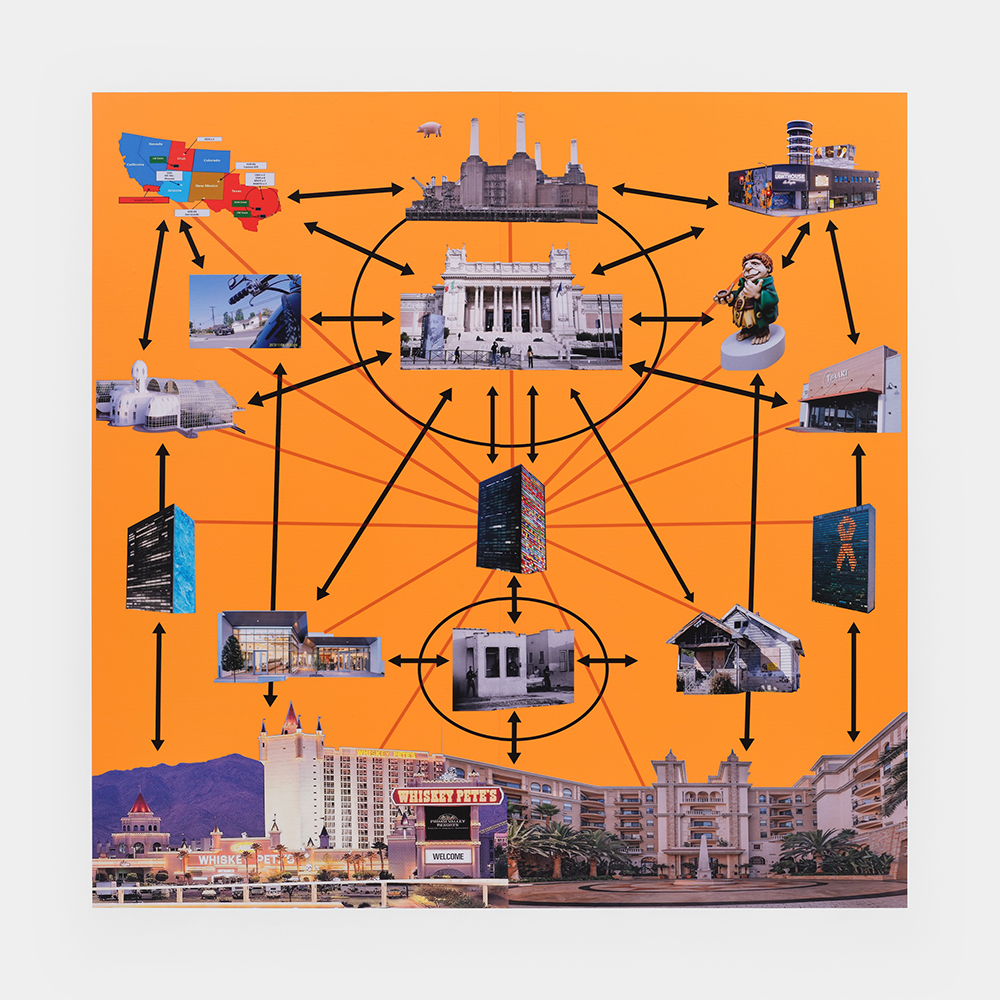

These are two of the many conjectural rabbit holes one might go down while trying to parse the meaning of the large-scale vinyl sticker A Conspiracy Theory About Jade Helm 15, JRR Tolkien, The Van Gogh Exhibit Where Amoeba Music Used to Be, And Other Things (all works 2024), in which both the National Gallery and Whiskey Pete’s are featured. The work, installed in Sebastian Gladstone’s main gallery, presents a flow chart on an orange ground with images of sites (also including a former Symbionese Liberation Army safe house, the ecological research facility Biosphere 2 and a Luxe fitness center) linked together in a byzantine network of arrows, lines and circles. The diagrammatic structure appears in another acrylic-on-aluminum work, Blue Opal, which connects various buildings and objects—from a leather office chair and a treadmill to an industrial plant, a prison fence and a stately manor—on a grid resembling an architectural blueprint, manifesting a desire to expose unseen infrastructures and systems of authority. It also structured the exhibition, as a series of long black arrows were printed in vinyl on the wall, moving the eye from one work to another.

Nick Angelo, A Conspiracy Theory About Jade Helm 15, JRR Tolkien, The Van Gogh Exhibit Where Amoeba Music Used to Be, And Other Things, 2024. Courtesy of Sebastian Gladstone.

Angelo’s invocation of icons, such as arrows, lines, circles and grids, elicits the sensation of conspiracy rather than offering a coherent ideology. This creates a kind of intellectual temptation on par with the gustatory temptations presented in the sumptuous, Dutch-style vanitas of fruit, bread and cheeses titled My God, Does He Eat Alone! (After Floris Claesz van Dijck). Angelo, who for years has meditated on the political, cultural and socioeconomic conditions of contemporary addiction (and who works with Community Health Project Los Angeles to provide clean needles to drug users), suggests in his work that conspiracy is another desired object that one might become addicted to.

This exhibition, “La Pensée Unique,” channeled much of what it feels like to wade through true and false conspiracy theories as we seek to understand the corporate and national interests that structure our lives. Because the actual network of power that perpetuates illness, addiction and poverty is complex and diffuse, having a stable theory of it is a kind of fantasy, much the same way that a dollhouse (an object Angelo explores in his dollhouse-like sculptural miniature A Celebration of the Union of Dr. Kris Kelvin and TINA Caruso, One for the Ages) fulfills a wish of stable domestic life. Angelo’s exhibition captured this conspiratorial impulse while also resisting its fruition. Instead, his work reflects on the abstract mechanisms and strategies of power that undergird those that are both visible and implied.