Yes, Shepard Fairey is a street art superstar, a highly collectible blue-chip artist, and a household name worthy of museum retrospectives. Fairey’s also a multiple-city muralist, a curator of talent with his own Subliminal Gallery and most recently a co-producer of the massive Art Alliance: “The Provocateurs,” extravaganza in Chicago—Lollapolooza’s answer to the art world.

However, Fairey will be the first to admit he couldn’t have gotten this far without a little help from his friends. Now, he can afford to pay them, and they’ve become assistants. A six-year veteran and Fairey’s right-hand man is Nicholas Bowers, an artist in his own right.

By day, Bowers handles all the production of the OBEY art-making machine. While he has no hand in Fairey’s creative concepts, he makes sure they are executed flawlessly: murals measure out, the fine-art screens are pulled and the stencils precision cut. Wherever the latest 100-foot mural may be (The Peace Tree on the Line Hotel in Los Angeles as of this writing, actually), thanks to Nicholas, it arrives prefab-style in a box: Stencils, paint, blades, etc., it’s all meticulously planned out (and large-format printed) ahead of time at the LA studio. Measure twice, cut once.

“You’d be surprised how many people can’t measure a building. Blueprints are wrong sometimes,” Bowers explains. “Last year in Vienna, we were doing a “Commanda” image (Shepard’s wife Amanda with a spray can) with a little bit of space up top for a flower, and the actual building was a weird shape. We started putting the flower up and we hear from the ground, ‘Yo, something’s off!’ Whenever you’re two inches from the wall on a scaffold, you don’t see the scale. Turns out, the building’s height was two-thirds what it was supposed to be. We had the stencil so we could crop it and save it, but, whew, it fit in there just perfectly.”

How does one get the coveted job of production manager for one of the world’s most favored vandals? It’s not from a job listing or a good resume. Sure, you have to have chops, and Bowers certainly does, but the rest may be left up to the universe. Bowers met Fairey in 2006, when he came to speak to the art department at Winthrop University in South Carolina, where Bowers attended undergrad as a printmaking and sculpture major. South Carolina is Fairey’s home state and Winthrop is the University where Fairey’s grandfather had been president in the ’60s (Fairey attended RISD). The two hit it off and kept in touch. Sometime later, halfway through graduate school at the University of Florida, a well-timed phone call saw Bowers pick up and move to LA. The rest is recent history.

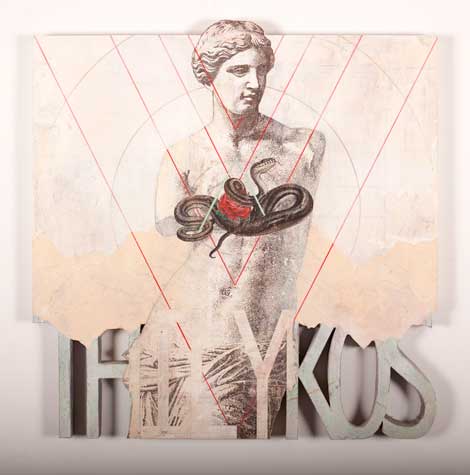

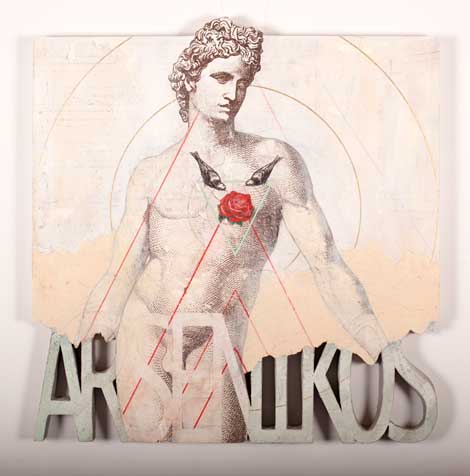

Bowers’ own work, to which he dedicates a majority of his off-hours, is stylistically opposite to what he does for his living. Like Fairey, it exudes a sense of history in its texture, color and concept; however, Bowers uses found ephemera, collage and what he describes as a “process of destruction” to elicit a more traditional, abstract response. Inspired by the tight pencil lines of his father’s blueprints, ’60s pop-art colors and even the dust on Greek monuments, each layer of paint on an image symbolizes a personal reference from Bowers’ Southern roots. His concepts may recall a recent life experience or latent memory, but they also draw on his knowledge of the craft. Does he have the same need for political comment in his work as his boss?

“I feel like I’m setting the stage for things we all go through as humans, so no,” explains Bowers. “For me, it’s more about technique and process. History, plus texture equals beauty.”

Among his many credits, Bowers’ artwork appears on an indie record cover and there’s a huge permanent piece of his hanging in Silver Lake’s notable Black Cat restaurant. He has also enjoyed inclusion in a few high profile group shows as well, including filmmaker Morgan Spurlock’s New Blood at Thinkspace in 2012, and he placed a well-received painting in 2014’s inaugural Cat Art Show, but Bowers is slow to show his work, as he modestly feels it’s still coming into its own.

“I’m right on the edge, where I need to be producing more and being involved more often, demurs Bowers. “I’d love to have two shows a year and be supported by my work, that’s the end goal. I’m not there yet, and it’s a battle, but I got a late start.”

Bowers is currently working on a full body of his own work to show in a gallery; during a recent museum trip to Charleston with Fairey he was asked to speak to the art department of his beloved alma mater, Winthrop University, in 2015, perhaps completing the karmic circle.

“I have a great gig, it’s awesome,” says Bowers, contemplating the trajectory of his career and readying himself for a whirlwind work-tour of Tokyo, Chicago and Berlin with Fairey. “I’m not in a hurry. De Kooning didn’t have his first solo show until he was 43, so I’ve got ten more years to work,” he adds with a laugh. “Shepard’s been great. He says, ‘use the studio, or whatever supplies’ I want, he’s been really supportive. So after hours I kind of clean the table off and bring all my stuff out and start working.”